Jazz Remembrance: Rivers Ran Deep

It was with great sadness that I learned that on the day after Christmas 2011 pneumonia carried off an underappreciated giant of jazz, saxophonist and composer Sam Rivers. His 88 years took him on a long journey from his midwestern origins to decades here in Boston and later in New York to a rich late period in the somewhat improbable locale of Orlando, Florida.

By J. R. Carroll.

Samuel Carthorne Rivers, Jr. was born in 1923. Think about that for a minute. He was three years older than Miles Davis and John Coltrane (and only three years younger than Charlie Parker). A peer, not a disciple, of jazz titans.

Like Lester Young before him, Rivers was a fully formed musician by the time he made his first recordings in the early 1960s. Because of his late arrival on disc, I believe there were some who thought he was part of the new generation of reedmen who came onto the New York scene at the same time, musicians like Marion Brown (1931-2010), Jimmy Lyons (1931-1986), Dewey Redman (1931-2006), Sonny Simmons (1933-), Frank Wright (1935-1990), Albert Ayler (1936-1970), John Tchicai (1936-), Archie Shepp (1937-), Pharoah Sanders (1940-), Charles Tyler (1941-1992) and Byard Lancaster (1942-).

But Sam Rivers’ creative life had a prehistory, most notably here in Boston, that set him apart from these younger musicians and shaped the paths he would follow over the past half-century.

Rivers came from a long line of musicians. His maternal grandfather, Marshall W. Taylor, published a compilation of spirituals in 1883 (and was one the first African-Americans to do so). His father, Samuel, a music graduate of Fisk University, sang gospel with the Silvertone Quintet, accompanied by his mother, Lillian, who, although trained as a sociologist at Howard University, was also an accomplished pianist and choir director.

Born in El Reno, Oklahoma (or possibly in Enid–sources disagree on this) on September 25, 1923, while his parents were on tour, Rivers spent his first decade in Chicago learning piano and violin from his mother and going to theatres like the Regal and the Savoy with his father to hear touring bands (Ellington, Basie, Lunceford, Calloway, etc.), as well as locally based musicians like Earl Hines. Sadly, in 1934 his father suffered a traumatic brain injury in a fall, and the family moved to Little Rock where his mother, now the family’s sole support, had accepted a position teaching at Shorter College.

The high school Rivers attended, St. Bartholomew’s, had a collection of donated instruments available for the students to study; he took full advantage of the opportunity to successively try the trombone, the soprano sax, the euphonium’s kid brother, the baritone horn, and, finally, the tenor sax. (The brass instruments fell by the wayside, but the saxophones—obviously—stuck.)

After graduating at the precocious age of 15, Rivers studied music at Jarvis Christian College in Texas and then joined the Navy when World War II broke out. Having secured a position with the Quartermaster’s office in Vallejo, California, Rivers was able to go into San Francisco in the evening and gig, most notably with bluesman Jimmy Witherspoon. While on the West Coast, he also got a chance to hear the legendary big band of Billy Eckstine (which included Charlie Parker, among others) on tour.

After the war ended, Rivers moved to Boston (where his father had been born and where his bassist brother Martin was living) in 1947 and took advantage of the G.I. Bill to attend the Boston Conservatory of Music. He studied with composer Alan Hovhaness, who introduced him to non-Western music and encouraged him to challenge musical orthodoxy and find his own path. He also formed a trio with stride pianist Larry Willis (not to be confused with the younger fusion pianist) and drummer Larry Winters, and occasionally jammed with other musicians like drummer Floyd “Floogie” Williams and saxophonist Leroy “Sam” Parkins.

He soon fell in with a group of musicians that included, among others, fellow Hovhaness student Gigi Gryce and the protean Jaki Byard, both of whom played with pianist/reedman Jimmy Martin’s Boston Beboppers (which Rivers soon joined), as well as the Perry brothers (violinist/saxophonist Ray and drummer Bey); drummers Alan Dawson, Bill “Baggy” Grant, and Clarence Johnston; trumpeter/bandleader Herb Pomeroy; pianist/bandleader Nat Pierce; trumpeters Joe Gordon and Lennie Johnson; trumpeter/arrangers Quincy Jones and Gil Askey; trombonist/arranger Hampton Reese; alto saxophonists Charie Mariano and Jimmy Tyler; tenor saxophonists Ghulam Sadik (Gladstone Scott), Andy McGhee, and Roland Alexander; baritone saxophonist Serge Chaloff; saxophonist Eddie Logan; multi-instrumentalist Ken McIntyre, and the tragically short-lived pianist Dick Twardzik. He also met his future wife Bea around this time.

Rivers later transferred to Boston University but was forced to drop out in 1952 due to ill health (possibly drug-related), which plagued him for the next several years and curtailed his performing (though he continued to compose). In 1955 a gig with a touring R&B group brought him to Florida. Living in Miami until 1957, he worked with his brother Martin playing with various jazz, blues, and R&B acts, including a stint backing Billie Holiday. (Regrettably, this period coincided with pianist Cecil Taylor’s years studying at the New England Conservatory; Taylor later provided one of the more detailed descriptions of the Boston scene but had little to say about Rivers, whom he did not meet until years later in New York.)

In 1958 Rivers returned to Boston, where he reconnected with Herb Pomeroy and, beginning in 1960, was a featured soloist in Pomeroy’s adventurous big band, which held forth weekly at The Stable until the club closed in 1962. (Sadly, Rivers never recorded with the Pomeroy band.) From time to time, Rivers continued to play backup for bluesmen T-Bone Walker, B. B. King, John Lee Hooker, and others, and may have recorded with J. C. Higginbotham and Paul Gonsalves. Around this time he also stepped out as a leader, as pianist Hal Galper recalls: “Sam had a quartet, originally, with Phil Morrison on bass and Peter Littman (of Chet Baker fame) on drums. Phil Moore was the pianist before I joined the band.”

In 1959 Rivers was introduced to a precocious 13-year-old student of Alan Dawson by the name of Tony Williams, who later recounted in a DownBeat interview that “Leroy Fallana, a piano player, asked me to join his band. I was about 14 or 15. He hired me, Sam Rivers, and a bass player named Jimmy Towles.” The quartet played at the brief first incarnation of Club 47 (now Club Passim), where Dawson had been performing with a trio. This led Rivers to a reformulated quartet with Galper, Williams, and bassist Henry Grimes.

Rivers and Williams were members of the Boston Improvisational Ensemble, which the latter described in a DownBeat interview as “doing things in the afternoons where they had cards and numbers and you’re playing to time, watches, and big clocks; playing behind poetry, all kinds of stuff.” The pair also played together in a quintet led by trombonist Gene DiStasio that included pianist Mike Nock.

In the interview cited above, Galper also stated that “Under Sam’s tutelage, we were the first to play free on standard tunes,” and in a 2007 interview at WKCR, he recounted that “‘time, no changes’ is something Rivers had worked out in the 50’s — calling out, for example, ‘E Anything’ on the bandstand meant a tonal center of E; this would be the only basis for improvisation.” Keep in mind that all this was going on here in Boston at roughly the same time that Eric Dolphy, Ornette Coleman, and Cecil Taylor were breaking similar ground in New York.

Late 1961 brought the opportunity for Rivers to participate in what is likely his earliest surviving recording date, an octet session for Blue Note led by Tadd Dameron, not released until many years later as part of the compilation The Lost Sessions. Along with three Dameron compositions, the date includes a gospel-inspired Rivers original, “The Elder Speaks” (a tribute to his father?), but his solos, even on this track, stay thoroughly “inside” and give little indication of the sorts of things he’d been up to in recent years with his own bands.

In 1962 Williams (who was heading off to New York to work with Jackie McLean) was replaced by drummer Steve Ellington and Grimes by a changing cast of bassists; an iteration of this group (with bassist Larry Richardson) performed on WGBH (or possibly WHDH) television in 1965, and eventually the quartet (with bassist Herbie Lewis) made its way to disc in 1967 on Rivers’ program of standards, A New Conception. Ellington also appeared on his next, pianoless–and, at the time, unissued–album, Dimensions and Extensions.

Rivers might have remained in Boston, where he actually made something of a comfortable living (for a musician) anonymously cranking out advertising jingles and tunes for song-poems. (I haven’t been able to track down the company he worked for, but it could conceivably have been this outfit.)

But in April 1964 he got the call (instigated by Tony Williams) from Miles Davis asking him to join his quintet for a few U.S. gigs and a tour to Japan, during which a number of the shows were recorded and eventually issued as Miles in Tokyo. Rivers was basically a placeholder until Art Blakey was ready to release Wayne Shorter to Miles, and he left the band shortly after returning home.

A month later, however, Rivers was back in the studio working on Tony Williams’ first LP, Life Time. Joined by bassist Richard Davis on two tracks (“Two Pieces of One: Red” and “Two Pieces of One: Green”) and Gary Peacock on a third (“Tomorrow Afternoon”)–all Williams originals–these trio recordings are very likely a good reflection of the earlier Rivers-Williams collaborations. Then, in September, Sam and Bea Rivers moved into an apartment on 124th St. in Harlem, and Rivers’ Boston years came to an end.

Others have written and will write about Sam Rivers’ years in New York, but there is one additional point that is pertinent to New England. Rivers’ role in spawning the loft jazz scene shouldn’t be underestimated. At a time when jazz clubs were on the decline and, in any case, many musicians were becoming dissatisfied with the ambiance of what were, after all, businesses selling food and drinks, Rivers had the imagination and persistence to see the possibilities in an overlooked space in a then little-known and little-visited part of Manhattan. Studio Rivbea became not only a home for musicians who liked to push boundaries and a nurturing ground for young players finding their voices but also a template for spaces like Ali’s Alley and The Kitchen and New England venues like New Haven’s Firehouse 12 and Cambridge’s Lily Pad and Outpost 186.

While this article has focused on Sam Rivers’ connections with Boston, I would be remiss if I didn’t offer a few examples of the immense creativity that grew out of those years.

Rivers commanded the full resources of the tenor saxophone, from the muscle of Coleman Hawkins and the lyricism of Lester Young to the multiphonics of John Coltrane and the ecstatic overblowing of Albert Ayler. Rooted in the music of the church and the concert hall and the great African-American big bands, Rivers’ solos and compositions drew, with varying degrees of freedom, upon a rich body of personal experience with blues, standards, bebop, Third Stream abstraction, atonal, and experimental music. He could play as inside as he wanted and as outside as his prodigious imagination could carry him.

At the freest end of the spectrum were the duo or small-group improvisations that explicitly eschewed any sort of template. These were acts of spontaneous composition right from the first note, without preconception, built from inspired invention and the intense interaction–intense listening–among musicians who possessed these skills at the highest level.

A superb example is this performance by Rivers, bassist Dave Holland, and drummer Thurman Barker, recorded in 1979 in Munich, Germany (note: the recording ends abruptly at the conclusion of part 6):

Rooted in bebop, Rivers could, of course, improvise fluidly over changes. Here are two quartet performances from 1989 with guitarist Darryl Thompson, bassist Rael Wesley Grant, and drummer Steve McCraven in Leverkusen, Germany:

Rivers never lost touch with his years backing blues and R&B artists; he may have jammed with Jimi Hendrix and was one of the few free jazz musicians who grasped what Miles Davis was up to in the 1970s. In this 1993 performance from Leverkusen co-leading a quartet with guitarist James “Blood” Ulmer (Kim Clarke and Aubrey Dayle are on bass and drums, respectively), Rivers fit into an electric ensemble as comfortably as he did into any of his acoustic groups:

As gifted as he was as a soloist, Sam Rivers was also an innovative composer of works for large ensembles, going back at least to his 1973 recording Crystals; these were often constructed of interlocking rhythmic layers inspired, at least in part, by West African drumming. When he and Bea relocated in 1991 to Orlando, Florida, where themes are associated with parks and not music, Rivers quickly ferreted out a subculture of frustrated musicians doing day gigs at Disney World who were eager to sink their chops into something substantial. Thus came about the Orlando Rivbea Orchestra, with whom Rivers worked for over twenty years. Here’s an example of the Rivbea Orchestra in action under his direction in 2009:

The documentation of Sam Rivers’ life and creative output is, fortunately, underway. His daughter, Monique Rivers Williams, has built a website devoted to his work, and Rick Lopez has put together an amazingly exhaustive sessionography of Rivers’ many live and studio recordings. I’ve attempted to supplement these efforts in some small measure by pulling together a host of scattered (and sometimes ambiguous or contradictory) facts about the fifteen years Rivers spent in Boston.

There is much more to be done, of course. I hope this article will prompt augmentation and correction from those who knew Sam Rivers and his Boston compatriots, something I expect to seek out in the coming year.

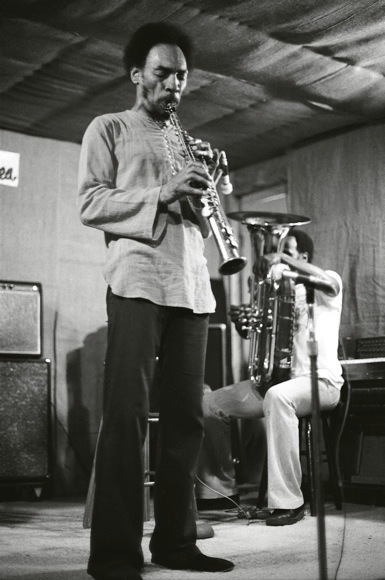

A splendid and necessary piece — one of my most cherished musical memories is seeing and hearing Sam Rivers at Studio Rivbea, around the time the photo in the piece was taken. I remember sitting down on the floor (there were no chairs) and being blown away with what I heard — he was a fiercely lyrical player in the mode of Ornette Coleman. I saw him several times after that — on one occasion at a jazz fest in Hartford, CT where I had a chance to go up and talk to him after the performance. I stammered — he was gracious.

Thank you for this great article. It’s the most thorough account of Sam Rivers’ Boston years I’ve seen.

I hosted his residency at NEC in December ’96, when he rehearsed and performed with the jazz orchestra playing his compositions and had a couple of dinner conversations with him about his Boston years. What he told me then is 100% consistent with what you write here. He had one of the most diverse and amazing careers in jazz history. I think that had a lot to do with his education and the depth and breadth of knowledge and musicianship skills he had, plus his creativity and fluid way of thinking, and a kind of realistic but persistent work ethic, or joy in working that wasn’t dependent on getting constant recognition from the media or music business.

The video at the bottom of Brian Carpenter’s blog post on Rivers showing him rehearsing his big band is a great snapshot of Sam offstage.

Allan, thanks for the vote of confidence on the article. The best sources were probably the interviews done at WKCR with Sam and with Hal Galper, but they were augmented with bits and pieces of many other books, articles and interviews, some more reliable than others. In a few instances it took a bit of detective work to tie together incorrectly spelled names of people Sam worked with. (One of the more surprising discoveries that came out of this was the fact that Sam and Tony had played in a quintet with trombonist Gene DiStasio and pianist Mike Nock.)

I’m looking at this article as a starting point for further biographical research, which will be a challenge given that Sam outlived just about everyone he played with (including, sadly, Tony Williams). Even more, I hope it will trigger discussion among those in the Boston area who knew Sam and might be able to shed some light on his years studying and working here.

Mr. Chase— Any chance you might have complete personnel on that NEC session on Dec 12 ’96?

Mr. Carroll— Any objections to my quoting this work in the Sessionography? The book is coming…

Nice article.

It has been confirmed without a doubt that Rivers was born in Enid, Oklahoma.

He gave a radio interview and confirmed twice that his birth place was indeed Enid.

El Reno, according to his birth certificate.