Book Review: “Heat” — An Imaginatively Imaginary Interview with Actress Jean Seberg

“Heat” is a fictional interview in which Stephanie Dickinson asks uncomfortably intimate questions and then imagines the answers Seberg might have given if she could speak from the undiscovered country she has inhabited since overdosing on sleeping pills in 1979.

Heat: An Interview with Jean Seberg, by Stephanie Dickinson, New Michigan Press, 80 pages, $9.

By Vincent Czyz

In his introduction to the selected writings of DT Suzuki, William Barrett lays out the Aristotelian universe: “a tight tidy rational whole where … everything occupies its logical and meaningful place in the absolute hierarchy of Being.” Its layered structure resembles an onion — seven concentric, transparent spheres revolving around the earth. Coming out of this tradition, a westerner’s encounter with Indian cosmology is a shock. As Barrett put it, he or she is “at first staggered by the vision of vast spaces, endless aeons of time, universe upon universe …” The creative mind of Stephanie Dickinson, author of Heat: An Interview with Jean Seberg, inhabits this eastern version of unending, non-Euclidean space.

Dickinson is not particularly interested in fitting neatly into a genre—this book is neither novel, nor novella, nor short story. She is equally unmoved by the standard Aristotelian mechanics of plot and narrative. Heat is a fictional interview in which Dickinson asks uncomfortably intimate questions and then imagines the answers Seberg might have given if she could speak from the undiscovered country she has inhabited since overdosing on sleeping pills in 1979. (“Try, suicide-girl, to polish the jagged lip of a can from your wrist,” Dickinson writes, providing a reminder of Seberg’s ultimate solution to her perennial inner turmoil.)

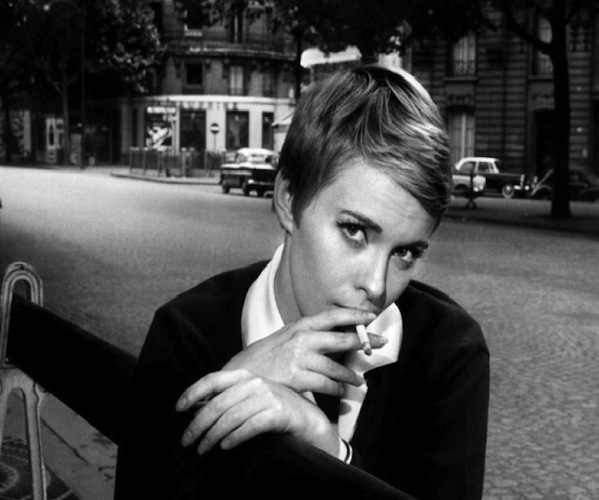

Born in 1939, Seberg is sometimes seen as James Dean’s later-on-the-scene, female counterpart. Both are from the rural Midwest (Dean from Indiana, Seberg from Iowa); both achieved fame through film; and both remained troubled Hollywood outsiders who died prematurely (though Dean was a ridiculously youthful 24 to Seberg’s 40). Both also found success early. Just before turning 18, Seberg landed the starring role in Otto Preminger’s Saint Joan—out of an alleged casting call of 18,000. Unfortunately, Preminger’s film was epic only in its failure, and it wasn’t until Jean-Luc Godard’s 1960 international sensation, Breathless, that Seberg’s name had any heft in the film industry—or outside it. Eventually, she abandoned Hollywood and acted only in European cinema.

Dickinson offers a kind of creative biography, by way of a fantasy Q & A, that concentrates on Seberg’s adult life. Having spent a good deal of time in the Midwest myself—Kansas to be specific—I cottoned to the way Seberg, as channeled by Dickinson, describes her home town experience: “Marshalltown had the landlocked foursquare light of smoldering hymnals. It shone from the red maples and elms, the green dripping emeralds from the branches. I left the town trees. Family. I eloped from tractor chug and roads of nowhere to go. Everything was thirst. Everyone knows your nightgown’s color when you arrive in the funeral parlor.”

Building pages out of striking phrases, sentences and images, Dickinson allies herself with authors such as John Edgar Wideman and Angela Carter, whose short stories resonate more with the principles of poetry than of prose. Tree roots, in Dickinson’s book, become “whitened eels,” and meringue is a “sweet bite of cloud.” There is also this verbal Polaroid of Seberg’s first pregnancy: “I listen to Diego’s every kick inside me, his tossing and turning, how the current in a river must sleep.” I found the metaphor exceptionally elegant and brilliantly apt.

Of course, like every other book, this one has its flaws. Chief among them is that the interviewer’s voice often veers too close Seberg’s—this isn’t your typical interrogator. For example, the interviewer’s preamble leading up to a question about Seberg’s first husband includes this observation: “Your affection for him [is] ephemeral and fading faster than the smell of his shaving cream.” The dialogue would have been a bit more effective had there been greater distance (and tonal difference) between interrogator and subject. And it would have helped if the questions had been a little more prosy, more clearly part of the Aristotelian universe. The other difficulty for me is that Seberg’s responses sometimes sound so disconnected from the question—or the question sometimes looks so much like a set-up for a particular response—the exchange feels contrived.

These drawbacks, however, are minor, and in this country, where bland prose crowds out the imaginative, where the so-called technical devices of “craft” are valued over vision, and sentences leave no aftertaste to savor, I was both deeply grateful and relieved to have stumbled on this slim volume.

Heat presents us with a story—a life—however obliquely approached, and Seberg, as given voice by Dickinson, is a darkly fascinating character. This is a book that you won’t read so much to see what happens next as to see how Dickinson words what happens next, to feel between your fingers the texture of Seberg’s psyche as though it were a butterfly wing whose color doesn’t rub off, to explore the shape left by this deceased actress, whom film transplanted from a small town in Iowa to the boulevards and cabarets of Paris.

Vincent Czyz is the author of Adrift in a Vanishing City. He is the recipient of the Faulkner Prize for Short Fiction and two NJ Arts Council fellowships. The 2011 Capote Fellow, his work has appeared in many publications, including Shenandoah, AGNI, The Massachusetts Review, The Georgetown Review, Tin House online, Louisiana Literature, Southern Indiana Review.