Book Review: Julian Assange Trades Hopes and Fears With Cyberpunks

Any book in which the fourth sentence is “The world is not sliding, but galloping into a new transnational dystopia” runs the risk of overstating its case from the get-go.

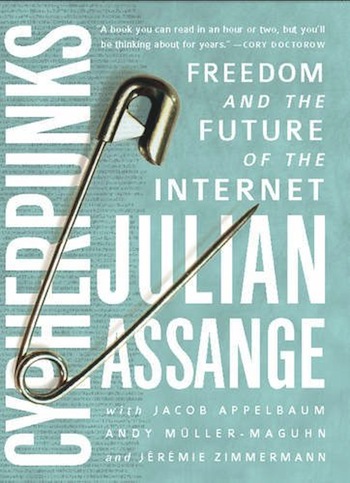

Cypherpunks: Freedom and the Future of the Internet by Julian Assange with Jacob Appelbaum, Andy Müller-Maguhn and Jérémie Zimmermann. OR Books, 196 pages, $16.

By Blake Maddux

In his introduction to Cypherpunks: Freedom and the Future of the Internet, Julian Assange—the founder of WikiLeaks and the subject of the new movie The Fifth Estate—writes, “On March 20, 2012, while under house arrest in the United Kingdom awaiting extradition, I met with three friends and fellow watchmen on the principle that perhaps in unison our voices can wake up the town.”

Cypherpunks is a transcription of that conversation. Assange’s interlocutors are Jacob Appelbaum, a founder of the San Francisco hackerspace Noisebridge; Andy Müller-Maguhn, a member of the German hacker group the Chaos Computer Club and co-founder of the European Digital Rights Association; and Jérémie Zimmermann, co-founder and spokesperson for La Quadrature du Net, “the most prominent European organization defending anonymity rights online and promoting awareness of regulatory attacks on online freedoms.”

According to a note at the beginning of the book, “Cypherpunks advocate for the use of cryptography and similar methods as ways to achieve societal and political change … The term cypherpunk, derived from (cryptographic) cipher and punk, was added to the Oxford English Dictionary in 2006.”

Although the history of the cypherpunks movement is referenced in bits and pieces, the book does not explore it in great depth. Assange, however, does speak briefly about the movement’s origins:

If we go back to this time in the early 1990s when you had the rise of the cypherpunk movement in response to bans on cryptography, a lot of people were looking at the power of the internet to provide free uncensored communications compared to mainstream media. But the cypherpunks always saw that, in fact, combined with this was also the power to surveil all the communications that were occurring.

As a result of the use (and abuse) of this power, Assange opines, “the internet, our greatest tool of emancipation, has been transformed into the most dangerous facilitator of totalitarianism we have ever seen … Left to its own trajectory, within a few years, global civilization will be a postmodern surveillance dystopia, from which escape for all but the most skilled individuals will be possible.”

Clearly, Assange is a bit of an alarmist. However, I found it significant that he did not write that the Internet was “once our greatest tool of emancipation.” By leaving this statement in the present tense, he seems to be allowing for the possibility that people might be able to use the Internet to liberate themselves from those who would use it to destroy principles of user anonymity and privacy.

Among those whom these four men claim are doing the devouring are some of the most popular social media and Internet websites on Earth.

Jacob Appelbaum says, “the people that created Google didn’t start out to create Google, to create the greatest surveillance machine that ever existed. But in effect this is what has been created” because “assholes do things with their power that the original designers would not do.”

Jérémie Zimmermann castigates Facebook, which he asserts “makes its business by blurring this line between privacy, friends, and publicity … So whatever the degree of publicity that you intend your data to be under, when you click publish on Facebook you give it to Facebook first, and then they give access to some other Facebook users after.”

Andy Müller-Maguhn makes a particularly good point about the consequences that come with the increasing ease and affordability of mass surveillance:

[I]n the old days, someone was a target because of his diplomatic position, because of the company he worked for, because he was suspected of doing something, and then you applied surveillance on him. These days it’s deemed more efficient to say, ‘We’ll take everything and we can sort it out later.’ … Because you never know who is a suspect.

The above has proved to be a bit of a premonition, as it came one year and two months before Edward Snowden’s revelation of the National Security Agency’s [NSA] vast surveillance program.

A recent Washington Post article based on NSA documents disclosed that “During a single day last year, the NSA’s Special Source Operations branch collected 444,743 e-mail address books from Yahoo, 105,068 from Hotmail, 82,857 from Facebook, 33,697 from Gmail and 22,881 from unspecified other providers … Those figures, described as a typical daily intake in the document, correspond to a rate of more than 250 million a year.”

To the extent that these entities—specifically Facebook —“have decided … to collaborate with the state to sell out their users and to violate their privacy and to be part of the system of control,” Appelbaum avers, “[t]hey are complicit and liable.”

Elsewhere in Cypherpunks, Appelbaum describes Facebook as being “the perfect Panopticon in some ways. (Not surprisingly, Zimmerman says that he does not use Facebook and Assange does not have a Twitter account.)

Of course, any book in which the fourth sentence is “The world is not sliding, but galloping into a new transnational dystopia” runs the risk of overstating its case from the get-go. Thankfully, however, the four men keep the hackneyed references to George Orwell and Aldous Huxley to a minimum (two in the case of the former — a mention of Big Brother and a quote — and a single use of the phrase “brave new world” in regard to the latter).

Moreover, it is easy to charge Assange with aggrandizing both himself and his fellow cypherpunks when he says, “perhaps there will just be the last free living people, those who understand how to use this cryptography to defend against this complete, total surveillance” and “I think the only people who will be able to keep the freedom that we had, say, twenty years ago … are those who are highly educated in the internals of the system.”

It is statements such as these that tag Assange as the least optimistic of the bunch throughout Cypherpunks. He remains steadfastly unwilling or unable to foresee anything but the worst-case scenario, which he describes as a state in which “[a]ll communications will be surveilled, permanently recorded, permanently tracked, each individual in all their interactions permanently identified as that individual to this new Establishment, from birth to death.”

The end result will be that “the freedoms that we have biologically evolved for, and the freedoms that we have become culturally accustomed to, will be almost entirely eliminated.” Perhaps this pessimism was borne of the fact that he has suffered the most as a result of having acted on the philosophy that he and his mates espouse.

Appelbaum (who has also had some unfortunate encounters with assorted law enforcement officials), Müller-Maguhn, and Zimmermann, on the other hand, show a few signs of pragmatic optimism. Appelbaum at one point asserts that “just because it is possible doesn’t mean it’s inevitable that we will go down this path, and it doesn’t mean that we have to get all the way to the point of every person being monitored.”

Zimmerman, meanwhile, is apparently willing to accept the possibilityof the rule of law to thwart the inevitable misapplication of surveillance powers: “We are beginning to see that as network citizens we have power in political decisions and we can make our elected representatives and our governments more accountable for what they do when they make bad decisions that affect our fundamental freedoms and that affect our fundamental freedoms and that affect a free global universal internet.”

He also reveals a smidgen of faith in the invisible hand, stating, “I’m convinced that there is a market in privacy that has been mostly left unexplored, so maybe there will be an economic drive for companies to develop tools that will give users the individual ability to control their data and communication.” Müller-Maguhn, finally, believes that “now finally there’s a generation of politicians coming up who don’t see the internet as the enemy but understand that it is part of the solution, and not part of the problem.”

Overall, Cypherpunks is a book for those who more or less agree with most of what its main author believes, and back most of what the other three do. Those unconcerned with technological spying will not be interested in having various scary scenarios articulated, but those with the jitters will be given plenty to think (and be nervous) about. Even those somewhat skeptical about the extent of the threat posed by mass surveillance will at least come away with some idea of what the worst might be.

Blake Maddux is a freelance journalist and regular contributor to DigBoston and The Somerville Times. He recently received a master’s degree from Harvard Extension School, which awarded him the Dean’s Thesis Prize in Journalism. A native Ohioan, he moved to Boston in 2002 and currently lives with his wife in Salem, Massachusetts