Book Review: “Double Indemnity and the Rise of Film Noir” — A Rehash

By Gerald Peary

The best part of the Silver/Ursini book is the padding, the last 40 pages in which the two authors go past Double Indemnity’s release to contextualize it within the generic stream of “film noir.”

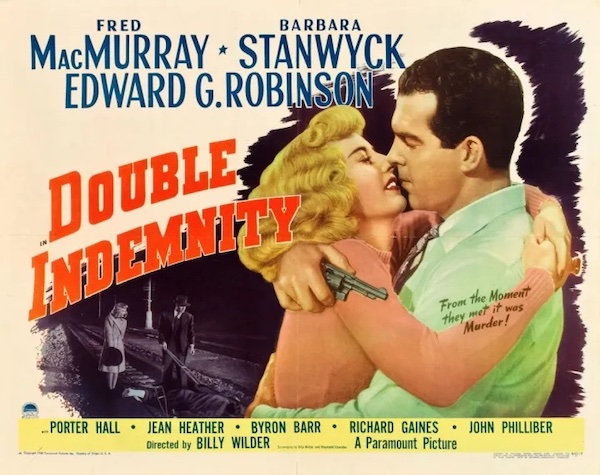

From the Moment They Met It Was Murder: Double Indemnity and the Rise of Film Noir by Alain Silver and James Ursini. Running Press, $30.

Did you know that James M. Cain, author of Double Indemnity and other hardboiled works, was once, for a brief time, the editor of the New Yorker? I didn’t. Nor that Barbara Stanwyck’s blonde wig for the film of Double Indemnity (1944) had been worn earlier by Marlene Dietrich in Manpower (1941). Nor that Dick Powell, tired of his high tenor in countless musicals, begged unsuccessfully to play the role of Walter Neff, insurance salesman, which was given instead to Fred MacMurray. Powell found his “noir” self afterward in Farewell, My Lovely (1944) and Pitfall (1948).

Did you know that James M. Cain, author of Double Indemnity and other hardboiled works, was once, for a brief time, the editor of the New Yorker? I didn’t. Nor that Barbara Stanwyck’s blonde wig for the film of Double Indemnity (1944) had been worn earlier by Marlene Dietrich in Manpower (1941). Nor that Dick Powell, tired of his high tenor in countless musicals, begged unsuccessfully to play the role of Walter Neff, insurance salesman, which was given instead to Fred MacMurray. Powell found his “noir” self afterward in Farewell, My Lovely (1944) and Pitfall (1948).

Are you fairly knowledgeable about American film history? Then Double Indemnity and the Rise of Film Noir offers very little fresh about the making of the classic “film noir” beyond little factoids like those above. The bulk of the information in this book can already be found in Roy Hoopes’s biography of Cain, as well as in various volumes about filmmaker Billy Wilder, director of Double Indemnity, and about mystery novelist Raymond Chandler, co-writer with Wilder of the screenplay. Granted, the scattered facts from these other volumes appear here in one convenient place, which is some kind of virtue for Silver/Ursini. But they’re offered in a more interesting, stylish way in other places, including the excellent Wilder critical studies by Ed Sikov and Joseph McBride.

Particularly egregious here is the skimpy, colorless telling of the Wilder-Chandler partnering, which came about because Wilder’s regular screenplay collaborator Charles Brackett needed a psychological break (he would return to co-write the 1946 The Lost Weekend), and James M. Cain was unavailable to adapt his book to the screen. The Wilder-Chandler relationship has been described many times in the past and often quite deliciously. It’s such a weird mismatch of personalities: the WASPY The Big Sleep novelist, gloomy, awkward, and antisocial, married to a woman much older than himself, and on the wagon from his alcoholism; and the ex-taxi dancer Jewish-Austrian emigré, an extroverted wit, who often interrupted their work day so he could chat on the phone with his girlfriends or go off for his elongated martini-with-three-olives lunches.

Besides Wilder and Chandler getting on each other’s nerves as they wrote, there is really nothing compelling or dramatic about the filming of Double Indemnity, given that almost all of the shooting occurred on the Paramount lot. The casting of the three leads — Stanwyck, MacMurray, Edward. G. Robinson — went very smoothly, with Warner Brothers star Robinson agreeing to third billing as long as he got the highest salary. Seemingly, the two other actors were fine about it. And there is no record of blow-ups on the set, of angry actors walking away, of feuds with Wilder. The filming went famously, maybe a little over budget. No problems here either. And though the Breen Office intervened a bit in the name of the Hollywood Code, the asked-for changes were very tiny.

Fortunately, the famous double-entendre sexual dialogue between Stanwyck and MacMurray remained in the film exactly as was written. Yes, the Code demanded that Stanwyck and MacMurray be punished for murdering Stanwyck’s husband. But Wilder didn’t compromise his principles by having Stanwyck shot dead by her lover/co-conspirator; it’s a dazzling scene. As for a mortally wounded MacMurray falling unconscious at the feet of Edward G. Robinson after the lighting of a cigarette? A fabulous moment, so good that Wilder chose to end his film there instead of with what he’d shot: MacMurray dying in the electric chair. To summarize: the movie on screen is exactly what Wilder wanted and it’s a pretty perfect masterpiece. Again, the story of the making of it, even in more skilled literary hands than those of Silver and Ursini, is not a very provocative one. Where’s the fun gossip?

The best part of the Silver/Ursini book is the padding, the last 40 pages in which the two authors go past Double Indemnity‘s release to contextualize it within the generic stream of “film noir.” A very convincing case is made that, though there had been “noirs” since 1940-41, the major cycle was post-Double Indemnity. It occurred mid-to-late ’40s and was spurred into existence by the artistic reputation of Wilder’s film. Silver and Ursini argue that “we cannot overstate the influence of Double Indemnity on the film noir movement. Before 1944 there was a trickle of titles. After there was a flood.” Some of the elements in Double Indemnity that the authors find in abundance in later noirs: flashbacks, ironic first-person narration, a “black widow” femme fatale as the precipitator of trouble, and “greed and lust that leads to murder…betrayal and death for the illicit lovers.”

Curiously, Double Indemnity was only a minor financial success when it was released. Was it just too nasty and unyieldingly cynical for the paying public, despite its obvious excellence? Wilder’s film managed seven Oscar nominations but without a win, The Best Picture of 1944 was almost a cultural rejoinder to it: the benevolent, humanist Bing Crosby priest movie, Going My Way.

Gerald Peary is a Professor Emeritus at Suffolk University, Boston; ex-curator of the Boston University Cinematheque. A critic for the late Boston Phoenix, he is the author of nine books on cinema; writer-director of the documentaries For the Love of Movies: The Story of American Film Criticism and Archie’s Betty; and a featured actor in the 2013 independent narrative Computer Chess. His latest feature documentary, The Rabbi Goes West, co-directed by Amy Geller, has played at film festivals around the world. His latest book, Mavericks: Interviews with the World’s Iconoclast Filmmakers, has been published by the University Press of Kentucky.

Tagged: "Double Indemnity and the Rise of Film Noir", "Double Indemnity", Barbara Stanwyck

The Dick Powell film mentioned here was titled “Murder, My Sweet” (1944), not “Farewell, My Lovely.” The latter is the title of the Raymond Chandler novel on which the film is based and the 1975 remake starring Robert Mitchum.