Poetry Review: “Catullus: Selected Poems” — A Comfortable Intro to an Uncomfortable Poet

By Jim Kates

Translator Stephen Mitchell serves Catullus best with the poems that don’t demand cleverness, where the sentiment is at least seemingly direct.

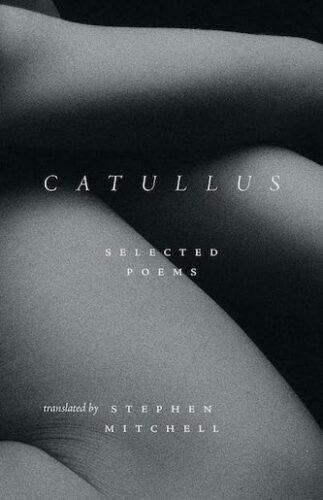

Catullus: Selected Poems by Gaius Valerius Catullus. Translated by Stephen Mitchell. Yale University Press, 168 pages, 26 pages

Gaius Valerius Catullus is the most contemporary of Classical Roman poets. Writing at the very end of the Republic, during the ascension of oligarchs and autocrats preceding empire, he is perhaps even too contemporary these days. Catullus looked deliberately back to Greek models, and unintentionally forward to us. He could pass as a neo-formalist sonneteer (see Poem 13) or as among the most confessional of post-modernists. But be careful: in Poem 16, omitted from Stephen Mitchell’s Catullus: Selected Poems, the poet warns against assuming the value of unwarranted confession.[1]

Gaius Valerius Catullus is the most contemporary of Classical Roman poets. Writing at the very end of the Republic, during the ascension of oligarchs and autocrats preceding empire, he is perhaps even too contemporary these days. Catullus looked deliberately back to Greek models, and unintentionally forward to us. He could pass as a neo-formalist sonneteer (see Poem 13) or as among the most confessional of post-modernists. But be careful: in Poem 16, omitted from Stephen Mitchell’s Catullus: Selected Poems, the poet warns against assuming the value of unwarranted confession.[1]

For good reason, Catullus has been translated over and over again, for every generation and in every formal shape and wild form. Does a new translation need to supply any justification? Or is simple exuberance and appreciation a good enough reason to bring a new Catullus into English?

Stephen Mitchell is the Broadway of literary translation. He has drawn material from a wide variety of disparate (sometime unlikely) sources and reduced them all to his own distinctive idiom. He’s glitzy and accessible, and almost uniformly entertaining. But every translation is a matter of making choices and, like the escapism of Broadway, Mitchell often leaves essential qualities of a complex original behind while he plays to an easy tourist crowd.

With his Catullus, the first choice Mitchell makes is to cherry-pick among the poems. There are few enough of these to begin with — the entire surviving corpus is only slightly more than a hundred — and so a selection is bound to be a small one in any case. Mitchell gives good reason for his selection of only half of the available verse: “I find many of the shorter poems rather weak … and the long poems at the center of the collection, despite their sporadic beauties, leave me cold.” In short, his is an idiosyncratic personal reading, with which no one can quarrel. But the effect for a reader — who is not Stephen Mitchell — is to encounter a kind of vasectomy of the Roman poet. The translator retains the action, but loses much of the potency. He has omitted some of the raunchiest and most fun, as well as some of the more mythologically dense, examples of Catullus’s verse.

In an introductory review for general readers, it might not be good form to hone in on just a few lines and pick them apart; but, with so many versions of Catullus around, it is the most succinct way to show how Mitchell has handled Catullus’s Latin.

Let’s look at how translator leaches the energy from a few of the poet’s most famous and exuberant lines:

da mi basia mille, deinde centum,

dein mille altera, dein secunda centum,

deinde usque altera mille, deinde centum,

dein cum milia multa fecerimus

conturbabimus, illa ne sciamus

Even if you don’t understand any Latin at all, just by looking you can see how the sounds repeat rhythmically — the consonants engaging a reader’s lips in the physical smack of osculation. There are only sixteen different words in the five lines; this intense repetition is the poet’s primary strategy. An approximately awkward literal version would be:

Give me a thousand kisses, then a hundred,

then another thousand, then a second hundred,

then up to another thousand, then a hundred

then when we have made many thousands

we will confound them, we will not know . . .

While Mitchell offers:

So come, sweetheart, and give me first a thousand

kisses, then you might add a hundred others,

then a thousand, and then another hundred

and then when we have added tens of thousands,

let’s go bankrupt and cancel the whole number . . .

He uses almost twice as many different words as the original, and is indifferent to the sound. I don’t quite understand the introduction of “come, sweetheart” in place of the imperative Da. The distracting metaphor of bankruptcy introduces an entirely different feel from the original; Mitchell’s speaker seems too busy counting to kiss — the exact opposite of the reckoning of the poem.

Too often, the translator simply uses too many words. In the caustic slapstick of 36, the lovely crack of Cacata carta — toilet paper — (I’d be tempted to use “shit sheets”) comes out “hundreds of pages smeared with bullshit.”

Mitchell serves Catullus best with the poems that don’t demand cleverness, where the sentiment is at least seemingly direct, as in No 31, where the poet returns to a place of comfort after hardship:

. . . How glad I am to be here,

not quite believing that I’ve really left

Bithynia and finished the long journey.

In his introduction to the Tao Te Ching, Mitchell wrote, “If I haven’t always translated Lao-Tzu’s words, my intention has always been to translate his mind.” In the poems he has chosen for this Selected, the translator has successfully translated Catullus’s mind. The original Latin words are provided en face. The reader who will be satisfied with that will find a comfortable introduction to an uncomfortable poet.

[1] “nam castum esse decet pium poetam / ipsum, versiculos nihil necesse est” — “while an honorable poet ought to be decent / himself there is no necessity for his lines to be so.”

J. Kates is a poet, feature journalist and reviewer, literary translator, and the president and co-director of Zephyr Press, a nonprofit press that focuses on contemporary works in translation from Russia, Eastern Europe, and Asia. His latest book of poetry is Places of Permanent Shade (Accents Publishing) and his newest translation is Sixty Years Selected Poems: 1957-2017, the works of the Russian poet Mikhail Yeryomin.

I’ve followed translations of Catullus but none seems to me to capture his vigorous spirt as well as Peter Whigham’s 1966 Penguin which has lovers having sex in a ditch . Wish I had my copy handy.