Arts Commentary: The Brave New World of Videogame Art

So let’s steady that swaying hive, put down the poking stick, and take a deep breath. Games continue to evolve in creative, unexpected ways, and the mechanics of gameplay can form the basis of intriguing and thought-provoking works of art.

By Margaret Weigel

Can videogames be art? That question—along with “do videogames cause violent behavior?” and “will prolonged gameplay make me go blind?”—is as old as (the original) Tron itself. The debate is akin to a hornet’s nest, mostly benign and easily ignored until someone takes a notion to give it a fresh whack it with a conceptual stick. Which is what prominent film critic Roger Ebert did in April 2010 with his article, Video Games can Never Be Art, published in the Chicago Sun-Times. “[One] might cite a immersive game without points or rules, but I would say then it ceases to be a game and becomes a representation of a story, a novel, a play, dance, a film,” said Ebert. “Those are things you cannot win; you can only experience them.”

The resulting buzz from the blogosphere was deafening. Google “video games as art” and you will get close to 160,000,000 results, including a lot of metaphorical angry hornets. The Smithsonian Institution, Guillermo Del Toro, and Salman Rushdie say yes, New Scientist and Ebert say no, and Wired magazine sagely intones that time will tell.

Although I didn’t review all 160,000,000 citations, sentiments online clearly favor the position that games are indeed art. A prominent argument is that games, well, include artwork, and that they are art. The site Creative Uncut is home to character designs, illustrations, and promotional art from a wide range of video games. The online gallery Into the Pixel has been featuring juried videogame art exhibits since 2004 and is sponsored by the Academy of Interactive Arts and Sciences.

Game art can be enjoyed on its own or repurposed in other creative formats. Machinima, for instance, typically uses captured footage of game play as the basis for a short, narrative movie. Operation Bayshield, considered one of the first examples of machinima, takes clips from the game Quake and converts them into . . . well, if not quite art, a clever synthesis of Quake’s online world and a coherent storyline. Video Games Live (warning: website blurb) “is an immersive concert event featuring music from the most popular video games of all time. Top orchestras & choirs perform along with exclusive video footage and music arrangements, synchronized lighting, solo performers, electronic percussionists, live action and unique interactive segments to create an explosive entertainment experience!”

If giving video game music a laser show/Mozart makeover isn’t art, I’m not sure what is. Then again, perhaps even more confusing than whether videogames are art is figuring out what constitutes art in the first place. Over the last decade, the debate over the legitimacy of videogames as art has raged on schedule; however, both videogames and the videogame industry itself have undergone serious transformations that challenge some of the old claims about the value of games in the aesthetic realm. The changes themselves can be examined in terms of how games are made and what constitutes a game.

Lin Ran’s The Boy Who Went Forth to Learn What Fear Was — one of the winning images in the 2007 Into the Pixel competition.

It used to be that only media companies with deep pockets had the resources to produce a complex and engaging videogame, says Philip Tan, the executive director of Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s GAMBIT game lab, but thanks to a proliferation of affordable production tools, the founders of Tale of Tales can produce a half a dozen artful and provocative gaming titles assisted by a handful of collaborators, allowing their unique (and not necessarily profitable) handiwork to shine. “The purpose of Tale of Tales,” the website states, “is to create elegant and emotionally rich interactive entertainment. We explicitly want to cater to people who are not enchanted by most contemporary computer games, or who wouldn’t mind more variety in their gameplay experiences.”

Offerings include 2009’s Fatale (based on the play Salome by Oscar Wilde), which “explores the story of Salomé in motion and stillness,” and 2008’s The Graveyard, “a quiet and short experience about death and life.” But is it art? While Tale of Tales likens Fatale to “an explorable painting,” they implore fellow game designers to shy away from making modern art in their RealTime Manifesto. “Modern art tends to be ironical, cynical, self referential, afraid of beauty, afraid of meaning-other than the trendy discourse of the day-,afraid of technology, anti-artistry.”

“Other [designers],” Tan opins, “want the cultural validity that the term conveys that comes with the term [art],” and actively position their games as art-ifacts. Mark Essen, a twentysomething, art gaming wunderkind, comes to mind. His work, characterized by chunky pixels and a retro arcade vibe, has been the toast of both the fringe and mainstream art scenes, and his resume lists dozens of art shows featuring his work. Essen’s oevre is considered art in part because both he and significant art institutions have declared it as such. My version of Pocket Solitaire, not so much.

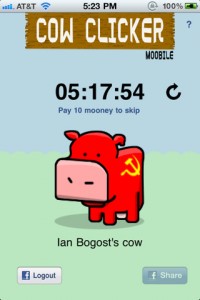

What to make of Ian Bogost’s Cow Clicker then? Cow Clicker, according to Bogost, is an online Facebook game intended to critique some of the less engaging elements of the genre: “Cow Clicker is . . . partly a satire, and partly a playable theory of today’s social games, and partly an earnest example of that genre.”

Cow Clicker is what the end product might be if a social game was designed by Luis Bunuel, in which literally nothing happens other than the actions around the game. “You get a cow. You can click on it. In six hours, you can click it again. Clicking earns you clicks. You can buy custom “premium” cows . . . and you can buy your way out of the time delay by spending it. You can publish feed stories about clicking your cow, and you can click friends’ cow clicks in their feed stories.” That’s it. No hay to buy; no new barns to build. Just circulation, customization, a lot of cow puns, and the existential despair of ultimately pointless clicking.

Perhaps we shouldn’t be asking whether or not videogames are art, but whether or not art is increasingly influenced by videogame principles. For instance, New York’s Eric Zimmerman’s game Sixteen Tons, which premiered at the Kai Lin art gallery in February 2010, appears to be a straightforward game of strategy but quickly morphs into a surprisingly meditation on commerce, cooperation, and social networks. And Brenda Brathwaite’s holocaust game similarly splits gameplay into a surface strategy and a much deeper, darker challenge.

The ubiquity of mobile technologies have encouraged game designers such as Jane McGonigal to use mobile phones to conduct large-scale, multiplayer games in city streets or alternative reality gaming. The game Cruel 2 B Kind, a collaboration between McGonigal and Bogost, requires participants to identity fellow players and slay them—verbally, that is, and with a stock compliment such as “Nice belt!” or “Have you lost weight?” Since players mingle with non-players on the street, the game quickly transforms into sidewalk performance art akin to Improv Everywhere as clusters of hipsters rush to compliment tourists, housewives, and grocers, who are both confused, blushing a little, and checking to see which belt they’re wearing today.

So let’s steady that swaying hive, put down the poking stick, and take a deep breath. Games continue to evolve in creative, unexpected ways, and the mechanics of gameplay can form the basis of intriguing and thought-provoking works of art. Even the shoot’em up genres can find new life in a machinima narrative. And if you think otherwise, I may need to level you with a snappy comeback about that fabulous new haircut.

Tagged: art, Cow Clicker, Fatale, GAMBIT, Into the Pixel, Machinima, MIT, Sixteen Tons, Tale of Tales, The Graveyard

I believe videogames are art, though I would be more convinced if they were generating the same kind of substantial criticism art has garnered for centuries. Chuck Klosterman raised a firestorm in 2006 when he asked where the Pauline Kael of videogame criticism was, suggesting that most consumer game criticism is either consumer guide advice or technical chatter exchanged among designers and hardcore fans. He responded to the attacks, including manifestos such as New Games Journalism, (NGJ) here. NGJ argues that videogames call for a new form of critical evaluation:

Sounds like a call for a tired return to Gonzo reviewing to me: how does one rationally discuss the ways “reality is remixed around you”—my reboot is your retread. The best arts criticism has always been about more than consumer advice and arguments among aficionados—it connects art to moral and cultural values, social issues, a broader audience. Do we talk about videogames in the same way we talk about films or other arts? If not, why not? And what does that say about the kind of art they are?