Film Review: Report from the 2019 Provincetown Film Festival, Part Two

By Tim Jackson

Finding independent films that may or may not receive wider distribution, as well as talking to filmmakers anxious to answer questions about their work, are great reasons to travel to the Provincetown Film Festival.

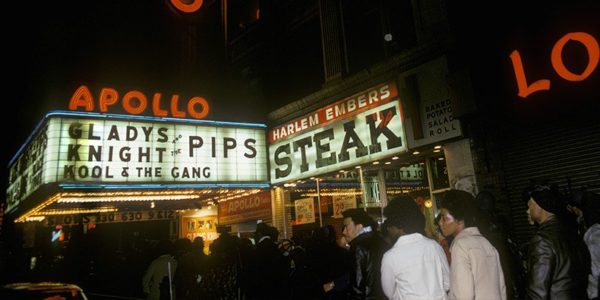

A scene from the documentary, “The Apollo.”

At this year’s Provincetown Film Festival I saw one great documentary, and then decided to take in some low budget narrative films. Finding independent films that may or may not receive wider distribution, as well as talking to filmmakers anxious to answer questions about their work, are two of the best reasons to travel to Provincetown. The festival always offers a generous selection of LGBQ movies; this summer, it reflected another cultural trend, with several films about aging (the boomers are getting worried) and female liberation.

The HBO documentary, The Apollo, brings a illuminating historical context to the theater history. The film cuts between archival footage and a rehearsal for a public reading by Ta-Nehisi Coates of sections from his book Between the World and Me. Coates’ meditation on black struggls compliments the achievements of the singers, dancers, and comedians who have performed on that venerable stage: Ella Fitzgerald, Duke Ellington, Dinah Washington, Billie Holliday, Smokey Robinson, Moms Mabley, Richard Pryor, Patti Labelle, James Brown, and many others. The film effortlessly weaves in history lessons on race and class. There are backstage interviews in which we learn little known facts about salaries, superstitions, and the booking practices at the Apollo, which began as a segregated burlesque hall in the early ’30s. Director Roger Ross Williams, the first African-American to win an Oscar for directing and producing the short film Music by Prudence, is a deeply humanist filmmaker and he was the perfect choice for this remarkable film.

I looked forward to Auggie because of the star turn it offered Richard Kind, who plays Felix Greystone. Kind, best known for his quirky supporting characters and voice-overs (American Dad), is an endearing presence. On his retirement, Greystone receives a pair of Auggies — virtual reality glasses — that projects a virtual companion who is generated out of the wearer’s personal tastes and desires. The complexities of this kind of techno-companionship were brilliantly addressed in the Spike Jonze film, Her. Unlike that film, Auggie never really takes off, partly because a small budget means limited settings and no special effects. Cutaways to Felix’s imagined companion fail to immerse us in an alternative reality; neither does the film resonate as a fable about the isolation of aging.

Always up for another low budget indie surprise, I wandered into Sister Aimee. In the ’20s, the Evangelist ministry of Aimee Semple McPherson made a global impact. Sister Aimee, as she was known, held audiences spellbound; she is alleged to have performed miracles. When McPherson disappeared on May of 1926 her sister claimed she had drowned. She mysteriously reappeared three days later, claiming to have been abducted — though that has never been proved. Despite the scandal, Sister Aimee’s celebrity grew. In their film, creators Marie Schlingmann and Samantha Buck imagine what might have occurred during those three days. Unfortunately, Anna Margaret Hollyman in the title role lacks the charisma necessary to convey Sister Aimee’s power and influence. The story attempts to be a satire (Sinclair Lewis pulls this off in his novel Elmer Gantry), but its social criticism is undermined by overacting and stagey scenes. Sister Aimee’s life deserves to be more than an exercise in awkward camp.

Driveways, directed by Korean-American Andrew Ahn, is a low key meditation on aging, friendship, and family. Kathy (Hong Chau from Downsizing) arrives with her young son Cody (Lucas Jaye) to clear out her late sister’s house, a hording nightmare. On the porch next door sits an old widower and war vet named Del (Brian Dennehy), who takes a detached interest in the mother and her son. Jaye, whom the producer discovered after hundreds of auditions, never plays Cody as cute — this is a smart, curious, video savvy kid who longs for guidance and friendship. Inevitably, Cody and Del will bond. Chao is convincing as a loving though overly cautious mom. Dennehy, who often plays characters bigger than life, gives an effectively gentle performance. The quiet brilliance of his film, particularly its heartbreaking final scene, reminded me of Edward Yang’s Yi Yi (2000). The director later told me that that the latter film was a huge inspiration. In Driveways, the revelations are quiet, the action is minimal, and the payoff is considerable.

Haley Bennett’s character develops a very strange diet in “Swallow.”

The John Schlesinger Award presented to a first-time feature filmmaker went to Carlo Mirabella-Davis for his film Swallow. Hunter (Haley Bennett) is a housewife in an arid marriage who spends her days in a house that feels more like a terrarium than a home. She dutifully serves the needs of her husband, but is met with cold disdain by her in-laws. Pregnant and alone most of the day, she finds herself increasingly compelled to consume dangerous objects. (The psychological disorder is known as Pica.) Mirabella-Davis uses this illness as the basis for an acidic fable about female discontent and desperation. The direction is patient enough (not sensationalist) to make the uncomfortable subject matter tolerable. Haley Bennett’s constrained performance is agile as well as visceral; I found myself chuckling at cringe-worthy moments. Bennett’s beautiful wounded face suggests myriad shades of repressed passion; yet she can explode at a moment’s notice. There is a pivotal scene with Denis O’Hare, who plays an abuser, that will blow you away. After the screening, I went for a beer with the first-time director, who teaches 16mm film production at a high school in New York. We discussed his approach to the production design and how, for instance, the furniture mimics the shapes of the objects consumed. I told him that the balance he found between dark humor and feminist fable reminded me of Florence Pugh’s performance in Lady Macbeth (2017). The director knew that film by heart.

A scene from “Imaginary Order.”

I also had an opportunity to talk with director Debra Eisenstadt following a screening of her film, Imaginary Order. Wendi McLendon-Covey (The Goldbergs, Bridesmaids) is Cathy, another troubled housewife in a cold marriage with problems piling up. My question to the director was: should I be laughing at this woman’s mess of a life while, at the same time, I’m cringing? Eisenstadt explained that that was exactly the response she was aiming for. As a mother of three young kids herself, she finds the chaos of motherhood to be both exhilarating and confounding.

In Imaginary Order, Cathy’s husband is always pecking away at the computer, even during breakfast. Her testy daughter closes herself off with earphones and hissy fits. After her husband leaves on a vacation with their daughter, Cathy, desperate for romance, has a sudden and brief dalliance on the kitchen floor with her next door neighbor’s husband, Paul. His wife (gorgeous Christine Woods) is in rehab. Paul’s son Xander (a creepy Max Burkholder ) sees the tryst between his father and Cathy. It turns out that Xander has developed a crush on Cathy and is now in a position to blackmail her. The film’s rhythms are quirky, even jittery; there is a constant sense that everything could fall apart any minute. The movie reminded me of Yorgos Lanthimos’ Killing of a Sacred Deer, which proffers a similarly dark tone and features another insecure yet intimidating adolescent. Eisenstadt responded that, though she loves Lanthimos, hers ia a much different film. The protagonist is female and her problems are grounded in the real world, far from the surreal dimension set up by a Lanthimos film. Imaginary Order was shot in nine days on a small budget. Held together by McLendon-Covey’s performance, the movie presents a brave, uncompromising story of female power.

Tim Jackson was an assistant professor of Digital Film and Video for 20 years. His music career in Boston began in the 1970s and includes some 20 groups, recordings, national and international tours, and contributions to film soundtracks. He studied theater and English as an undergraduate, and has also has worked helter skelter as an actor and member of SAG and AFTRA since the 1980s. He has directed three feature documentaries: Chaos and Order: Making American Theater about the American Repertory Theater; Radical Jesters, which profiles the practices of 11 interventionist artists and agit-prop performance groups; When Things Go Wrong: The Robin Lane Story, and the short film The American Gurner. He is a member of the Boston Society of Film Critics. You can read more of his work on his blog.

Tagged: Auggie, Driveways, Imaginary Order, Provincetown Film Festival 2019, Provincetown Film Festivall, Swallow