Film Review: At the Boston Underground Film Festival — “Knife+Heart” and “Mope”

By Isaac Feldberg

My mind is busy considering the presence of two distinctly engrossing thrillers of sex and violence set within the adult film industry, one a vividly romantic neo-giallo fairy tale, the other a discomfiting, tragicomic spiral into murder and depravity.

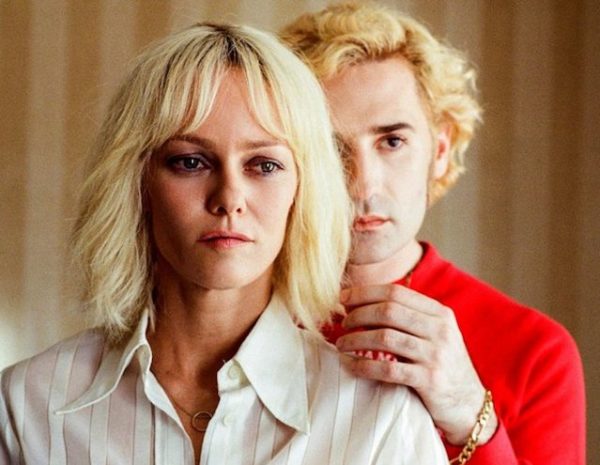

A scene from “Knife+Heart.”

Attending a film festival as intentionally off-kilter as the Boston Underground Film Festival can feel a bit like diving headfirst into the cult section of your local video store.

The fest — which this year ran from March 20-24 at the Brattle in Cambridge — has long considered itself a cinematic danger zone, a space in which all things strange and singular screen before before moviegoers more daring and open-minded than the crowds typically found at upper-crust affairs like Cannes and Sundance.

Suffice to say, BUFF is not the kind of place one expects to leave mulling congruities and consistencies; eclecticism is rather more the mission statement. But while it’s true that there’s no simple manner of — nor purpose served by — imposing a grand theme over this year’s crop of entertainingly uncanny selections, my mind is still busy considering the presence of two distinctly engrossing thrillers of sex and violence set within the adult film industry, one is a vividly romantic neo-giallo fairy tale, the other a discomfiting, tragicomic spiral into murder and depravity.

Knife+Heart (screening at the Brattle on April 6), from the French auteur Yann Gonzalez, is an intoxicatingly rich text, beguiling and thoughtful in its conception of queer cinema as a medium of long-buried desires and fantasies, even as it revels in getting high off its own lurid, green-and-red neon aesthetic. Its chief influences — De Palma, Argento, and Bava, with splashes of MTV scenography and a scene that recalls Warhol’s Blow Job — are not acknowledged so much as violently muddled in a cocktail glass, the flavors twisting and blurring together into something new, and tasty.

Set in 1979 Paris, the film focuses on a troupe of gay porn stars led by the obsessive Anne (Vanessa Paradis), who’s reeling from a failed romance with her longtime editor (Kate Moran). She drinks too much, she can’t let go of her ex — and, adding to those problems, a man in a leather mask is killing off her actors. I know, c’est la vie, right? An early scene begins in a club, two strangers locking eyes, and ends in a bedroom, one submitting to the other and discovering, to his abject terror, just what’s necessary to get him off. (Two words: switchblade dildo.)

As tone-setters go, it’s an euphorically out-there one, and the rest of the film follows through on the surrealist passion contained within it. Anne mounts a new production and finds her own emotions bleeding over into it, so much so that the serial killer thriller unfolding around her is practically unnoticed at first. Her mind is in the movie as much as on it.

It’s not just Anne. All the characters in Gonzalez’s work find release through seeing their most closely held fantasies on-screen. The film suggests that there is a surrender implicit in falling into a movie that’s not dissimilar to sexual submission. For Knife+Heart‘s vivid world, the movie screen exists as a dark mirror for its characters’ worst impulses, but also as a blank canvas onto which they project their most impossible, and lascivious, dreams. There’s something poignant in that, sometimes even tragic, and the campier elements of Gonzalez’s film are careful not to belittle it.

His approach to the film’s porn is playful, cheesy; the same can be said of its murders, some of which Anne repurposes as dramatic grist for her productions. It’s rare to see a movie this philosophical about not only pornography but also its value as emotional relief for queer folk, more accustomed as they are to repressing and concealing desire in the name of survival.

When Anne restages one of her actor’s murders for the film, it’s a loopy bit of insight into her headspace, but it also simultaneously codes filmmaking as a method through which Anne and her actors can come to terms with an attack against one of their own. It’s an outlet where they can be themselves but also acknowledge, even immortalize, the trauma of being punished for being themselves. Such trauma processing through art becomes especially crucial when the police officers assigned to the case are loathe to validate what’s happened, let alone investigate it; Anne’s cheeky subversion of this on set feels particularly triumphant.

A scene from “Knife+Heart.”

As Anne finds herself on a collision course with the killer, the film’s sense of unreality intensifies, its style remains exultant, and the smoke-in-your-eyes poetry of its conclusion leaves you buzzing. Knife+Heart has an erotic pull so potent it borders on cinematic hypnosis; I’d suggest you give into it.

Mope, from director Lucas Heyne, does not hold up well on its own terms, let alone when compared to something as artful and deliberate as Knife+Heart, but seeing the two films close together does feel like looking at a photo negative in order to more fully appreciate aspects of the original image.

Essentially a Pain & Gain for the American porn industry, though it inexplicably leaves out the go-for-broke audacity of that Michael Bay satire, the movie follows two wannabe porn stars who dream of breaking big in the biz. It’s based on a true story that ended in blood-stained tragedy (though one that’s nearly a decade old now and so likely out of mind and sight for most in the audience). But Mope conducts itself more like a grim-hued buddy dramedy, zeroing in on the friendship between Steve Driver (Nathan Stewart-Jarrett) and Tom Dong (Kelly Sry) as they navigate the lowest rung in the porn world.

The pair are “mopes,” poorly paid adult actors who appear in group scenes or in background shots. For one reason or another they lack the talent to move up the ladder. A good comparison point, at least from the perspective of character, is The Disaster Artist, another movie about quixotic dreamers struggling to make the world see in them what they so clearly think of themselves. Steve and Tom talk a big game; raised on such a steady diet of misogynistic skin flicks they’ve developed a cinephile’s appreciation for their shooting styles, not to mention a geeky obsession with emulating their actors’ behaviors. They talk about reaping the sexual and commercial benefits of becoming major porn stars as the stuff of destiny. Problem is, the dream’s a delusion. Neither of them have what it takes, and their self-belief is more entitlement than enterprise.

Heyne is bent on highlighting the gross realities and everyday humiliations endured by these characters; they agree to do “ball-busting” scenes, among other degrading acts. Rather than face the ignominy of this stage in their careers they grow near-religious about envisioning themselves as experimental porn stars, braver and better than any of those commercial sellouts who’d never dare. It’s a coping mechanism, and an increasingly doomed one, as these two are brought increasingly incontrovertible — and to Steve, mentally destabilizing — proof they’re deluding themselves. Most pornography is in its very construction intended to stroke the male ego, to put the viewer in an intoxicating position of power over the women on camera; Mope follows two men who’ve confused this artifice with reality, and suggests when they realize this it can only end in violence.

It’s an interesting premise for a character study about men becoming increasingly disconnected from reality in an industry that at a base level demands that they pervert their views of sex and self. If only Heyne committed to this critique; instead of courting empathy for his characters he only cracks crude jokes at their expense. Mope wants to be a goofy workplace comedy, a Taxi Driver-lite potboiler, and an expose of how the porn industry dehumanizes its workers. It hits none of these notes quite right as it scrambles to tap them all.

This points to a kind of immaturity on Heyne’s part, especially given that Mope escalates until it’s a full-on tragedy of affronted masculinity, rapidly curdling into something more repulsive than any of the sexual degradations the characters have endured beforehand. There’s nothing funny about the fates of these two guys, ugly though they often are. And yet the last shot in the movie is a shitty punchline, a visual gag that quickly undermines the trauma preceding. Apparently, Heyne thought the whole thing was pretty funny all along.

Still, there’s truth to the worlds of both Mope and Knife+Heart, and ample space in moviemaking to explore the porn industry at least twice over, as a human-created space for wish fulfillment that can be cathartic when escaped to but horribly destructive when exposed as a fiction.

Knife+Heart gives itself fully over to the fantasy. Both as a movie itself and in its narrative vision, it’s the cinema as fugue, near-phantasmagoric in how it views adult film as a boundless pleasure dome in which romantic obsessions and past traumas can be negotiated and processed. In reinterpreting its characters’ worst impulses on celluloid, then letting them watch the end product from the safety of a movie theater, the film goes so far as to say these characters can change, can be healed, too — just by having a place to properly identify that which afflicts them. It’s a lovely idea. I think it’s probably true.

A scene from “Mope.”

Mope, by contrast, lowers itself into the American porn industry’s seediest, most squalid subsectors and examines the cost of remaining there on two guys raised on a vision of adult film that’s irreconcilable with the ones they end up making. I’ll stop short of saying that their vision veers in any way that’s close to the very French, very gay porn of Knife+Heart, because it doesn’t. As Mope spells out repeatedly, its two leads are not just straight but aggressively so. At one point, a director accuses Steve of being queer and he snaps, beating the guy to the ground. It’s actually a turning point in the film, the moment when you realize this guy’s never going to go anywhere worth following, and it is inextricably tied to the over-inflated male ego that will ultimately pop and leave Steve with nothing to fall back on save an act of unconscionable violence.

The violence of Mope, ultimately, is its reason to exist. The story that it should have been offers both a challenge to a porn industry that stokes misogyny with countless terabytes of men dominating women to take their pleasure, and a rebuke of guys like Steve and Tom who feel cuckolded when their reality doesn’t mesh with that incel fantasy. The Mope you’d expect ends with a ringing condemnation of both. There should be an acknowledgment that pornography is still an artifice, an especially skin-deep one when made in the back alleys of modern-day Hollywood. But the movie that ended up being made is too straight — and I mean that in every sense — to wade very deep, to take a strong stance on the forces shaping its characters, to really do much more than train the camera on them as if to guffaw and say, “Isn’t this wild?” It’s a movie set within an exploitative, dehumanizing incarnation of the porn industry that reserves all its contempt for the guys trying to penetrate it. And it doesn’t see the problem with that.

Much of this comes down to setting. Rage, domination, and humiliation are unfortunate hallmarks of modern American porn; ‘70s French porn is more self-consciously silly and whimsical, filled with comically mustached cops and ejaculations that erupt like out-of-control fire hoses. Viewed through a sociological lens, one era of adult film is more deserving of a cinematic love letter; the other, a cease and desist.

Gonzalez’s film belongs to a different era and offers a queered perspective and, for both of those reasons — as well as the fact it was made by an visionary, not a voyeur — it has something more interesting to say about its subject. Beneath all its flashing lights and coquettish entreaties, Knife+Heart seeks something no one in the world of Mope believes authentic: a conception of the erotic as sacred, as divine. The cinematic expression of this erotic is, then, not only admirable on artistic grounds but because everyone caught up by its expression — director, star, and audience all — finds in it a kind of freedom. Only through unconditional surrender, the film intimates, can come an equally unconditional release.

Isaac Feldberg is an entertainment journalist currently based in Boston. Though often preoccupied by his on-going quest to prove that Baby Driver is a Drive prequel, he always finds time to appreciate the finer things in life, like Michael Shannon.

Tagged: Boston Underground Film Festival, Isaac Feldberg, Knife+Heart, Lucas Heyne, Mope