Poetry Review: Leonard Cohen’s “The Flame” — The Errant Canadian Comes Home

Leonard Cohen reinforces this dedication to lyricism with striking humility in his final book.

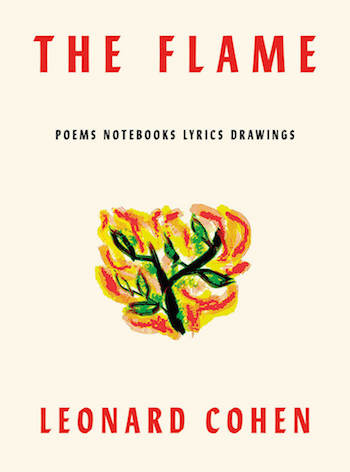

The Flame: Poems, Notebooks, Lyrics, Drawings by Leonard Cohen. Edited by Robert Faggen and Alexandra Pleshoyano. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 288 pages, $28.

By Robert Israel

On November 6, 2016, Donald Trump won the presidency. I immediately booked a flight to Toronto to distance myself from our national malaise. The next morning the Toronto Star was slipped under my hotel room door. It reported that Canadian poet and songwriter Leonard Cohen was dead at age 82.

It is rare when a writer not only achieves popularity, but is revered by his peers. But our northern neighbors treat their artists in a markedly non-competitive spirit. The Star splashed Cohen’s life and works across several full pages, reprinting “Bird on the Wire,” a poem/ballad about his restless search for personal liberty.

During his lifetime, Montreal-born Cohen achieved global cult status. Back home, Canadians viewed him as un Canadien errant — a wandering Canadian. In 1979, Cohen recorded a musical version of Un Canadien Errant, by Antoine Gérin Lajoie, written in 1842. (“Je me souviens” – “I remember” – a line from that poem is found on all Quebec auto license plates). Lajoie speaks of the melancholy in the Canadian character (and in Cohen’s) — what it feels like to be forlorn while in exile from one’s homeland.

In The Flame, Cohen’s last book, the errant and weary artist finally returns home. The volume’s poems, lyrics, notebook entries, and drawings were written while he was wandering in India, Italy, Israel, Iceland, the States, Greece, and Europe. Taken as a whole, the work expresses the longings of a writer in search of physical and spiritual fulfillment, captured nicely in his six-line poem, “What I Do”:

to live in a hotel

in a place like India

and write about G-d

and run after women.

It seems to be

what I do.

Cohen searched for God all his life (he practiced both Judaism and Buddhism) and he unabashedly pursued women, never marrying. He was candid (even self-deprecating) about his voracious sexual appetite, titling his 1977 album Death of a Ladies’ Man and naming one song “Don’t Go Home with Your Hard-On.” Yet it would be a disservice to dismiss Cohen as a writer with only two things on his mind. The Flame reveals him to be a gifted craftsman who is more than willing to tackle the intractabilities of the human condition.

In the poem “Happens to the Heart,” he takes a close look at how spaces in the human heart serve as repositories for emotion, dismay, and even fleeting triumph. He writes with despair about the violence in the world and his disdain for war. He shares his conversations with Roshi, his Buddhist master; these poems come off as koans, or riddles, designed to reveal the haplessness of logic when it is engaged in the pursuit of true enlightenment.

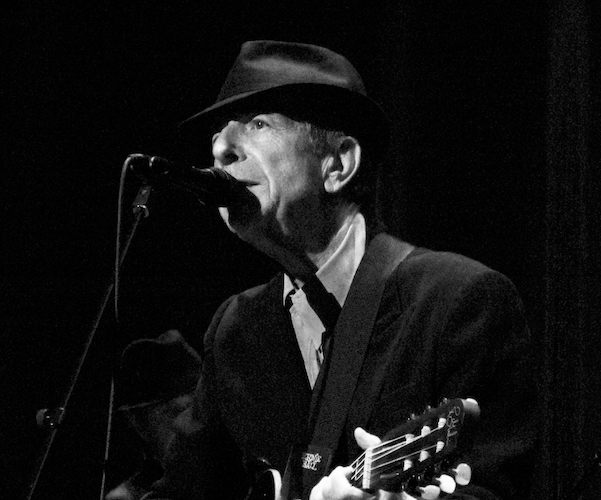

Leonard Cohen at the Arena in Geneva, 27 October 2008. Photo: Wiki Commons.

Ultimately, this volume is Cohen’s effort to provide an honest self-appraisal. He laughs at his own foibles. His drawings — most of them pen and ink self-portraits — show a man with saggy jowls and puffy eyes who endures everyday aches and pains.

And, like the rest of us, Cohen grapples with mortality, rehearsing the ways he might face the inevitable. Stricken with severe physical ailments near the end of his life, he devoted himself to finishing The Flame, which was completed by editors Robert Faggen and Alexandra Pleshoyano, along with Cohen’s son, Adam. In one of the volume’s most poignant poems, “”I Pray for Courage,” he confesses: “I pray for courage at the end/ to see death coming as a friend.”

Leaving my Toronto retreat after a long weekend, I re-read the clippings of Cohen’s life from the Canadian newspapers as the plane descended over New York. Joni Mitchell once called Cohen “a holy man on the FM radio.” But he was more than just an iconic troubadour with a spiritual bent. He was a poet who labored to distill emotions, impressions, exasperations, fears, and joys into tightly rendered lines. He reinforces this dedication to lyricism with striking humility in his final book.

Robert Israel writes about theater, travel, and the arts, and is a member of Independent Reviewers of New England (IRNE). He can be reached at risrael_97@yahoo.com.