Book Review: “Impossible Owls” — Beauty on the Margins

Brian Phillips uses the essay form to map the limits of America’s cultural-historical imagination, from our highest achievements to our kitschiest expressions of who we think we are, and who we think everyone else is.

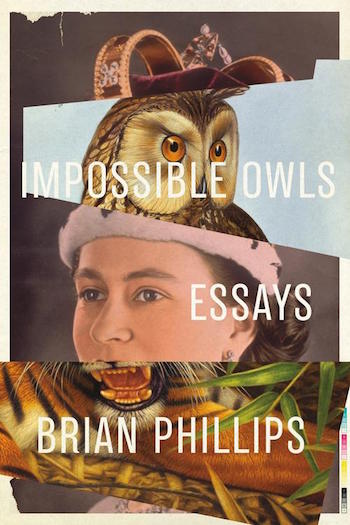

Impossible Owls by Brian Phillips. FSG Originals, 352 pages, $11.

By Lucas Spiro

There’s a reason why some sports writing also happens to be great writing; sports are stupid and meaningless, so the prose has to be good. There is no inherent value to participating in the overhyped spectacle, which is a good thing, and I wish it were even more true. When Walt Whitman suggested we “go forth awhile, and get better air in our lungs… [and] leave our close rooms” to watch a game of baseball, he wasn’t talking about today’s capitalist version of Major League Baseball. He was talking about a cultural activity people played because they liked it, an amateur social diversion, historically explicable, yet somehow mysterious.

Sports also lends itself nicely to narrative, or, rather, narrative finds a purpose in sport. No one really cares that the Dodgers won the World Series in 1988, but we remember Kirk Gibson’s home run in the bottom of the ninth in Game One. Not the mere fact of the home run, which is just another point in an ocean of points, a stat. We remember how it’s told: the setting, Vin Scully’s call, Gibson as he wills life into his battle-worn legs, “like a horse trying to get rid of a troublesome fly.” The labored trot. The fist pump. Tommy Lasorda running in that Tommy Lasorda kind of way.

It’s a moment that defies the limits of experience and becomes myth. “In a year that has been so improbable,” Scully said at the time, “the impossible has happened.” Scully’s call reiterates what Red Smith wrote about Bobby Thomson’s shot heard around the world in 1951: “Now it is done. Now the story ends. And there is no way to tell it. The art of fiction is dead. Reality has strangled invention. Only the utterly impossible, the inexpressibly fantastic, can ever be plausible again.” The Giants won the pennant and we passed through the limits of space-time. This is where Brian Phillips takes you in his volume of essays Impossible Owls.

Before I mislead you any further, I should say that Impossible Owls is not a collection of sports essays, although it includes pieces on sports. The opening foray, “Out in the Great Alone,” is about tracking the 2013 Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race from its origin in Anchorage, Alaska to where it finishes in Nome. Hardly an ordinary sporting event. The first paragraphs are a description of the Farewell Burn, where “[t]undra burned to rock; 345,000 acres of forest—more than 530 square miles—disappeared in flames,” after a sweeping fire in 1977. In the already unforgiving Alaskan terrain and weather the colossal burn forces teams of sled dogs “to be dragged across hardened mud and gravel. Runners broke; tree shards snagged tug lines; speeds dropped to three or four miles per hour.” This “nightmare” is also described by “novelist Gary Paulsen,” Phillips writes, “who ran the Iditarod twice… as a place where mushers literally go mad… ‘a place beyond all reason.’” The actual distance of the Iditarod is uncertain, but Phillips says it’s “about the distance from Carnegie Hall to Epcot,” which, in Impossible Owls, means more than just a couple of helpful landmarks. Phillips uses the essay form to map the limits of America’s cultural-historical imagination, from our highest achievements to our most kitschiest expressions of who we think we are, and who we think everyone else is.

Brian Phillips — Photo: FSG Originals.

Phillips strikes a familiar posture in his essays. Impossible Owls inherits and blends the styles of Hunter S. Thompson, Tom Wolfe, and David Foster Wallace, but with more humility and, at times, insecurity. Because the personal “creative nonfiction” essay is so popular these days, I’ve concluded that a lot rests on the writer’s ability to choose a subject. At a glance, it would seem Phillips chooses his subjects at random and, there may be something to that; yet he seems to be following his obsessions. Impossible Owls has essays on subjects as varied as sled dog racing, sumo wrestling, the British royal family, ‘90s sci-fi television, UFOs, Yuri Norstein, “a great, if tragically self-defeating, Russian Artist” and “[c]onsidered by many the finest animator in the world.” He writes about man eating tigers and the contradictions of conservation in India, and a multi-layered personal essay about the town in Oklahoma where he’s from.

He layers most of the pieces in the book, writing in multiple directions at once, but always moving toward a horizon of meaning, finding illuminating corollaries because of the way he looks at the world. He meditates a good deal on impermanence and paranoia. In “Out in the Great Alone,” he learns to fly a tiny plane from an Alaskan “bush pilot.” One of his lessons is landing on a frozen lake after his pilot plays dead. He pulls it off, recognizing that he is “still here.” To some, this might be too much about the narrator, to which I say, so what? If you’re not boring, you can inject yourself into the reportage all you want. And he justifies it thematically. “Who knew what would be there tomorrow?” he reflects when the race is over.

And it hit me that that was exactly the point of the Iditarod, why it was so important to Alaska. When everything can vanish, you make a sport out of not vanishing. You submit yourself to the forces that could erase you from the earth, and then you turn up at the end, not erased. I’d had it wrong before, when I’d seen the dog teams as saints on the cusp of a religious vision. It was the opposite. Visionaries are trying to escape into something larger. Mushers are heading into something larger that they have to escape. They’re going into the vision to show that they can come out of it again. The vision will be beautiful, and it will try to kill you. And (oh by the way) that doesn’t have to be the last word. That’s why you go to the end of the world—to lose yourself. And not to.

In fact, one of the frustrating things about Impossible Owls is the imbalance of Phillips’ presence in the essays. Sometimes he vanishes completely; other times he’s filtering everything through his psychological state. When he is in Japan to study the ancient art of sumo wrestling, a tradition that has been around for centuries, he becomes severely depressed. “I drifted through the city like a sleepwalker, with no sense of what I was doing or why,” Phillips recalls, refusing to confront some “crisis” on which he doesn’t elaborate, “pulling the curtains closed on the part of [his] mind that wanted to name it out loud.” Finding himself. And not. Another layer to this particular piece is his fascination with the celebrated Japanese writer, Yukio Mishima, who lead a small group of reactionaries on a doomed attempt at a coup, a mission that ends with the leader committing seppuku, requiring his friend to cut his head off in a “death agreement.” The friend, Hiroyasu Koga, went on living a quiet, obscure life, having once remarked that “to live as Japanese is to live the history of Japan.”

You could make that statement about anywhere, but it’s more palpable in some places than others. In Japan you have the incongruences of difficult histories and ancient traditions existing alongside the cutting edge of technology. In the American dessert, where the UFOs make contact and the first atom bombs were tested (the ones that we would eventually drop on Japan), you can find herds of oryx; alien deer imported from Africa for atomic scientists to hunt for sport. The nuclear technicians are gone, but the oryx are still there, “unmistakably from where they’re from… They had nothing to do with the atom bomb, nothing to do with war, nothing to do with anything. And yet … They were beautiful.” Impossibly beautiful.

Something strange, something bewildering happens at the margins. You have to go out and confront it. The essays in Impossible Owls do just that.

Lucas Spiro is a writer living outside Boston. He studied Irish literature at Trinity College Dublin and his fiction has appeared in the Watermark. Generally, he despairs. Occassionally, he is joyous.

Tagged: Brian Phillips, FSG Original, Impossible Owls, Lucas Spiro, essays, non-fiction