Film Review: “Gimme Danger” — A Fun House Story of The Stooges

The documentary is a highly enjoyable musical and social history of the group and its times, showing how The Stooges went against the grain of those times.

Gimme Danger, directed by Jim Jarmusch. Screening at the Kendall Square Cinema, Cambridge, MA

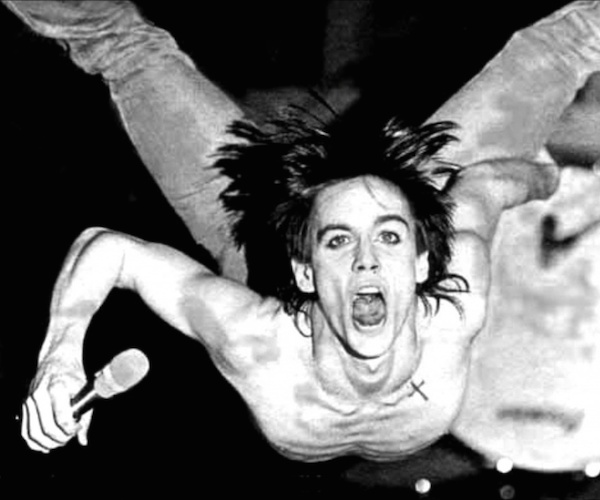

Iggy Pop in “Gimme Danger.”

By Betsy Sherman

A more adorable anecdote you couldn’t find than the one that comes up part way through Jim Jarmusch’s new documentary Gimme Danger, which tells the story of the brief but earth-shattering existence of the band The Stooges. Iggy Pop, a.k.a. Iggy Stooge, says that his late band-mate Ron Asheton actually tracked down Moe Howard’s phone number and called the bowl-coiffed one to ask if it was alright for the newly signed band to continue to use that name. “I don’t care what the fuck you call it,” said the legendary eye-poker, “as long as you don’t call it Three Stooges.”

It’s arguable that both aggregations had an influence on the punk movement, but to focus on the rockers, after their flame-out, the kids who loved them would go on to start bands like The Ramones, The Cramps, The Dead Boys, Sonic Youth and The Damned.

Other kids, like Akron native Jim Jarmusch, would go on to make movies that didn’t fit the mold of either Hollywood or the sensitive strain of American independent cinema typified by, let’s say, John Sayles. Jarmusch, who has become known for minimal plots presented in a deadpan style, wears his heart on his sleeve for this unabashed tribute to The Stooges. The documentary is a highly enjoyable musical and social history of the group and its times, showing how The Stooges went against the grain of those times. And you can’t go wrong sitting at the feet of the charismatic, worldly wise Iggy, whom Jarmusch has used as an actor in Dead Man and Coffee and Cigarettes. Here he’s seated in a throne-like chair and billed in the credits with his birth name, “Jimmy Osterberg as Iggy Pop.” Gimme Danger has a crackling texture, with amusing footage from archival sources, previously unseen footage and photographs of the band, and, to illustrate some stories, funky animation by James Kerr.

The Stooges came into being in 1967 and, with some personnel changes, lasted until early 1974. They made some of the most viscerally powerful music in rock—my all-time favorite album is their second, Fun House, where the core group was joined by sax player Steve Mackay. Their live shows featured, as Jarmusch wrote in the production notes, “a snarling, preening leopard of a front man who somehow embodies Nijinsky, Bruce Lee, Harpo Marx, and Arthur Rimbaud” (and who went on to a solo career that still rages). As chronicled in the movie, The Stooges were never any good at selling records. Three of the four original members, Iggy, Ron Asheton and Scott Asheton, enjoyed a “reunification” (Iggy’s preferred term) tour in 2003. Ron died in ’09 (there is some archival interview footage of him), and Scott Asheton and Steve Mackay died in the period since they were interviewed for the documentary.

The band was shaped by its birthplace, Ann Arbor, Michigan. Iggy speaks of a desire to translate the “mega-clang” of the factories into music. Next to that working class milieu was the University of Michigan, progressive in politics and in the arts. Inspired by Harry Partch, Iggy made his own instruments, one using a blender. He and his mates looked not only to other cultures, but also back on the evolutionary scale. On stage, the singer moved like a primate, and he says that “in the Ashetons I had found primitive man.”

In this way, The Stooges were in line with the experimentation and liberation that made the ‘60s the ‘60s. But only up to a point. There isn’t a molecule of idealism in their sweetly concise songs “No Fun” and “I Wanna Be Your Dog,” and only people who could never connect with Woodstock would peg 1969 as “another year with nuthin’ to do.” The Stooges became the “little brother band” to the MC5 but didn’t want anything to do with that band’s ally, John Sinclair, and his radical White Panther Party. Iggy says that when Sinclair asked The Stooges to perform for demonstrators at the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago, “I didn’t know what to say, so I somersaulted around the room.” He speaks disdainfully of peace-and-love pop created in corporate boardrooms (Jarmusch doesn’t make the easy go-to and play a clip from a flash-in-the pan group, but selects Crosby, Stills and Nash’s “Marrakesh Express”).

Drugs and alcohol played a large part in the downfall of The Stooges. During the tour for Fun House, bassist Dave Alexander was kicked out of the band when he was too messed up to play; he died at age 27. The man who signed both The Stooges and the MC5 to Elektra Records, Danny Fields, recounts the giddy heights and downward spiral (there’s a wonderful documentary about him, Danny Says). In spite of his boosting, the label dropped the band after two albums. A second phase of the band featured James Williamson on lead guitar. Iggy describes how Williamson’s style had an effect on his vocals (“James finds every corner of a musical premise and fills it with detail. I had to go an octave above Fun House to find space James didn’t occupy”). In 1972, Iggy met David Bowie; the star produced the band’s third album in London (with a name change to Iggy and the Stooges). However, Bowie’s manager, Tony DeFriese—described by Iggy as a Colonel Tom Parker—was just another guy out to exploit them.

Jarmusch’s mixed media montage makes the documentary a fun-house. The Three Stooges, colorized in psychedelic hues, pop out now and then playing instruments, and Yul Brynner in The Ten Commandments pops out because Iggy’s bare-chested stage persona was inspired by movie pharaohs. Another fun pop-out is Nico, Velvet Underground band-mate of John Cale, who produced the album The Stooges. She spent a torrid week with Iggy in the band’s communal house, and apparently was, to the other Stooges, the icky girl who infiltrated the boys’ treehouse.

Betsy Sherman has written about movies, old and new, for The Boston Globe, The Boston Phoenix, and The Improper Bostonian, among others. She holds a degree in archives management from Simmons Graduate School of Library and Information Science. When she grows up, she wants to be Barbara Stanwyck.