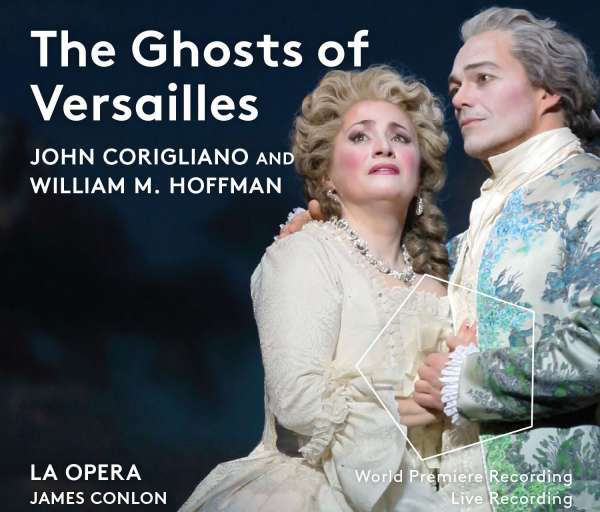

Classical CD Review: John Corigliano’s “The Ghosts of Versailles” (Pentatone)

Ghosts seems to be trying to be all things to all listeners — edgy, nostalgic, farcical, adventuresome — and, in so doing, manages to not be a particularly satisfying drama.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

“This is not opera! Wagner is opera!” sings the outraged “Woman with Hat” at the end of the first act of John Corigliano’s grand opera buffa, The Ghosts of Versailles. In the context in which that line appears, the stage – on which an entertainment organized by the ghost of the playwright Beaumarchais is descending into chaos, as Figaro steals the necklace of Marie Antoinette from Count Almaviva that Beaumarchais intends to sell in order to avert the Queen’s impending execution — has just been infiltrated by a “Rhieta orchestra” made up of chorus members playing kazoos; the Wagnerian leitmotif that swells at the cadence of the Woman’s observation is but icing on an operatic cake made out of just about every theatrical ingredient imaginable. In that alone, Ghosts is distinctly Wagnerian.

And there are, in fact, many more debts to Wagner (not to mention Verdi, Puccini, Bernard Hermann, Witold Lutoslawski, and others) peppered throughout its several-hundred pages. Indeed, Ghosts must rank as one of the most self-referential of recent operas, sometimes maybe a bit too much so for its own good: it gleefully plunders Mozart, Bellini, Rossini, Verdi, and others, and its libretto, by William M. Hoffman, offers its share of lines (like the Wagner one above) that are designed to play off a knowing audience.

Corigliano and Hoffman wrote the piece between 1983 and 1991 for New York’s Metropolitan Opera; at the time, it was the first new opera commissioned and premiered at that house in twenty-five years and, today, stands as one of just five new operas James Levine commissioned and conducted at the Met in his four-plus decades leading the institution. Remarkably, the present recording from Pentatone, a quarter-century after Ghosts’ 1991 premiere, marks the first time it’s appeared on disc (a telecast of the original production can be rented or streamed with a subscription on the Met’s website). So the big question is: was this recording worth the wait? And the answer is a perfectly equivocal yes and no.

Based loosely on the last of Beaumarchais’ three Figaro plays, La Mère Coupable, Ghosts’ few musical shortcomings and the more significant problems with its libretto haven’t really been resolved in the last twenty-five years. The plot remains convoluted. The gist of it follows the ghost of Beaumarchais’ efforts to spare the ghost of Marie Antoinette (with whom he is in love) her execution; he intends to spirit her away to America where they (as mortals) might live out their days together, “as history intended.” His scheme, which involves Figaro stealing the aforementioned necklace from Almaviva, runs into trouble when Figaro gets his own ideas about what to do with the jewels. Eventually everyone ends up imprisoned with the Queen, who realizes, as Beaumarchais is about to release her from her cell and effect his plan, that fate must run its course and she must die; afterwards, she and Beaumarchais can (and do) spend eternity together in the next world.

Listening to Ghosts, it’s best to check expectations that it operates on the same level as The Marriage of Figaro or The Barber of Seville at the door: Hoffman’s libretto runs the gamut from the vulgar to the profound and Corigliano’s score follows closely along, but the former rarely packs the depth, subtlety, wit, irreverence, or charm of Da Ponte or Sterbini. Rather, Ghosts seems to be trying to be all things to all listeners — edgy, nostalgic, farcical, adventuresome — and, in so doing, manages to not be a particularly satisfying drama. Indeed, given the familiarity of many of these characters, there’s surprisingly little emotional payoff at the end. Yes, Beaumarchais and Marie Antoinette drift off into eternity together but so what? Nearly all of the opera’s characters remain largely cardboard cutouts and, even in a fine performance, it can be difficult to feel too much sympathy for any of them.

The only exception to this rule is Marie Antoinette, who’s given a strikingly compassionate depiction, especially in Act 2. There, using actual transcriptions from her “trial” and chillingly depicting the depravity of mob rule, the second half of Ghosts paints a picture of this doomed woman far removed from the cartoonish imitations of her that have endured since her lifetime. And, given the braying of certain political entities these days, this element of Ghosts’ narrative echoes with particular force on the current recording.

If only the same could be said of all its characterizations. This is one of the opera’s significant flaws. So is the disorientation about what, exactly, Ghosts is: comedy, drama, tragedy, love story, or something else? Certainly, elements of each are present over its near-three-hour duration. But Ghosts’ confusion about this seemingly mundane detail only feeds the frenzy that makes it all seem more than a little neurotic. And the less said about the tortured statement Ghosts attempts to make about purpose of art the better: suffice it to say, by the end of the opera, it all rings a bit hollow.

But does any of this matter? More than a few canonical operas, after all, thrive despite subpar, labyrinthine, and/or inane libretti and plots. Indeed, that seems to be a required trait of some recent American operas in particular: A Quiet Place, The Death of Klinghoffer, and McTeague, among them. So in this regard Ghosts is at least in good company. Still, it’s hard to shake the feeling that, had the libretto been better focused and its aim run more true, the opera somehow could have been much more. And this is due in large part due to its score.

Indeed, Ghosts is largely redeemed by its music. Corigliano ably mimics the styles of Mozart, Rossini, and assorted others. He laces his writing with plenty of trademark nods to the avant-garde that fit the horrific moments (and the ghostly ones) in the story well. The several second act passages that juxtapose the musical styles of the late-18th and 20th centuries are particularly effective. If the libretto can’t ever quite decide what it is, at least Corigliano’s one of the most innately theatrical composers alive today and he’s supplied music that fits each scene smartly and dramatically.

Much of this comes across on the present recording, in which there is, technically, more than a little to admire. The recorded sound is bright and lively. Balances between voices and orchestra are excellent. Despite the fact that this recording comes from live performances, there’s minimal audience noise and not too much extraneous sound coming from the stage: these ghosts are light-footed, indeed.

Alas, the casting is rather mixed and doesn’t always live up to the quality of the Met’s excellent original one. Patricia Racette, for instance, proves a sympathetic Marie Antoinette here, though the wide, warbly vibrato present in nearly everything she sings and her occasionally wayward intonation is distracting and often results in making her diction unintelligible; Teresa Stratas simply created this role on a higher level.

As the villain, Bégearss, Robert Brubaker well conveys the character’s menacing, evil intent but the upper ranges of his voice often sound forced and, generally, he seems to be out of breath. His “Aria of the Worm,” Bégearss’ chilling Act 1 introduction, is adequate but isn’t, vocally, in the same league as Graham Clark’s defining account of the same.

Similarly, in the small but memorable part of Samira the Entertainer, Patti LuPone is passable — but she doesn’t embody the part anywhere near as brilliantly as did Marilyn Horne in 1991: Corigliano’s knowing send-up of the Cult of the Diva and the conventions of bel canto simply works best with an opera singer who is established in that repertoire and is such an ingénue, as Horne did and was. And some of the lesser roles, including Kristinn Sigmundsson’s Louis XVI, simply don’t leave much of an impression at all.

On the other hand, the excellent Christopher Maltman proves a winning Beaumarchais, robust of tone and heart. As Figaro, Lucas Meachem turns in a fleet performance, droll and amusing in the first act but revealing more nuanced depths in his character as the dark second unfolds. And Joel Sorensen’s Wilhelm ably comes across as the toadying lackey he is.

The play-within-the-opera’s women – Lucy Schaufer’s Susanna, Guanquin Yu’s Rosina, and Stacey Tappan’s Florestine – are all particularly fine. Corigliano wrote some fiendishly difficult music for these characters to sing and, in the stratospheric parts, Tappan, especially, stands out for the brilliance of her coloratura. Both Joshua Guereros’ Almaviva and Brenton Ryan’s Léon are well sung, as is Renée Rapier’s Cherubino. Indeed, the Act 1-quartet (“Look at the green grass in the glade”), a gentle parody of Mozart led by Rapier and Yu, is one of the disc’s highlights, sweet and beautifully realized.

In the pit, James Conlon delivers a well-paced, vibrant account of the score. The LA Opera orchestra is certainly at home in the portions of Ghosts that allude back to Classical- and Romantic-era operas, but they really shine in Corigliano’s sinewy Modernist writing, especially in Act 2. Overall, they prove an impressive ensemble: athletic, colorful, versatile.

And it’s these qualities that, ultimately, make this recording burn hotter than cold. Casting- and libretto-warts aside, Corigliano’s music for Ghosts is easily as significant, inventive, and interesting as what’s to be found in Nixon in China, The Voyage, or The Great Gatsby. That it took too long to get this piece on disc is a shame — but at least now it’s documented and widely available. And, for that, many thanks are due Pentatone and LA Opera.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette

Tagged: John Corigliano, LA Opera, Pentatone, The Ghosts of Versailles, opera buffa