Arts Interview: The Late E.L. Doctorow — Reduced to Art

“When people ask how I became interested in history, I answer it was through an interest in popular culture and disreputable genres.”

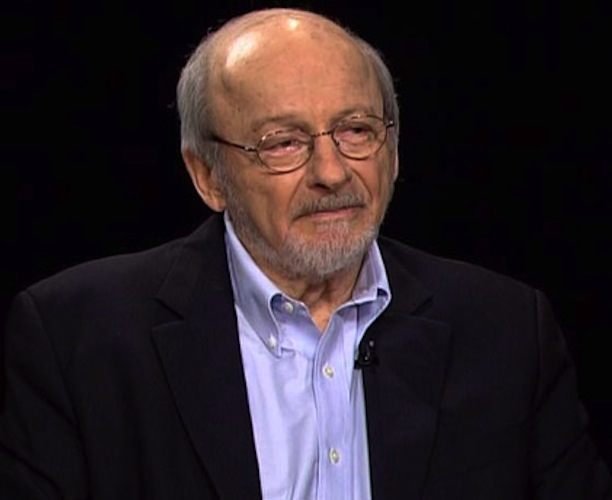

E.L.Doctorow — as a writer, his abiding concern was with fiction’s combative connections with history.

By Harvey Blume

I was saddened to learn that E.L. Doctorow is no longer with us, having passed away, Tuesday, 7/21/15, at age 84. He was one of my favorite writers, with the ability to turn from the plain, functional, reportage-like prose of his classic, Ragtime, which evoked so much of early twentieth century America, to the flowing poetic lines of Billy Bathgate.

If Ragtime were Doctorow’s only style he might be pegged a descendant of John Dos Passos, an early master in weaving narrative threads together. Billy Bathgate, however, suggests another comparison, which I hope will not seem too far-fetched, namely to Italo Calvino, who made it a point of principle to conjure up a new style with each novel.

It’s undeniable, though, that Doctorow was throughout concerned with history, as opposed, say, to fable, which engaged Calvino. Doctorow’s novels manifest this preoccupation, this abiding concern — the novel v. the historical monograph, fiction v. supposed fact. So do his essays, notably his remarkable “False Documents.” If you are interested in what postmodernism was all about — I get it if you prefer to forget the whole damned discourse, though it’s unlikely to forget you — this is a clear and intelligible place to start.

This is not the place nor am I necessarily the critic to give E.L. Doctorow his full due. But I can’t help but wonder about how much space John Updike got in the NY Times obit for Doctorow. Updike was a novelist of sensuous surfaces, Doctorow of historical depths. It was an inexplicable misjudgment for the Times to have allotted Updike’s views pride of place in an obituary for Doctorow.

That said, I had the pleasure of interviewing E. L. Doctorow for the now defunct Boston Book Review in an exchange entitled “Reduced to Art” (1994).

Arts Fuse: For various reasons, including difficulty in categorizing a book I was writing, I became interested in the issue of genre in contemporary literature. That led me to your essay, “False Documents,” a superb piece I’ve returned to again and again.

Doctorow: I wrote “False Documents” because I was astounded by some of the reaction to Ragtime. People seemed to think it was somehow a transgression to incorporate historical figures into a fiction although I had spent my youth reading books that did just that. The Three Musketeers has Cardinal Richelieu as a character. In War and Peace, Napoleon and all his generals appear. What, then, was so transgressive about what I’d done in Ragtime?

I felt what was being called into question was fiction itself. Somehow a reduced notion of fiction’s legitimate territory had become prevalent. I didn’t subscribe to that notion. “False Documents” — Kenneth Rexroth’s marvelous phrase, for which I credit him in the piece — was a useful way for me to articulate my own presumptions, and to understand that fiction was, in fact, a system of knowledge that might even be superior to the social sciences or any of the other disciplines that incorporate its techniques without admitting it.

Arts Fuse: In your view, fiction is not advancing. It is trying to hold its own against an onslaught.

Doctorow: Exactly.

Arts Fuse: Just to do the kind of thing Tolstoy or Dumas did as matter of course you need polemical reinforcement.

Doctorow: The perception of fiction had changed. They had put us on the reservation, as it were. And I was saying, no, we’re going to break out.

You will find, historically, that fiction writers always use whatever form of accreditation is possible for their work. Cervantes, for instance, claims he found the manuscript of Don Quixote and had it translated. Defoe said he was the only the editor of Robinson Crusoe, not the author. It’s a way of lending authority to the fiction. Fiction claims and adopts the prevalent authority. With regard to Ragtime, authority had to do with belief that we live in an empire of fact, an empirical reality. I said, I’ll give them facts, all they facts they want; I’ll make up all these wonderful facts, you see.

So it’s kind of a defiant reassertion of the importance of fiction. It’s also wanting people to recognize that stories control us. For all our pride in objectivity and scientific thinking, we’re still controlled by stories, including, obviously, the stories of the Bible. We conduct our lives by stories.

Arts Fuse: When traditional genre melts down at the current rate, a kind of panic sets in. People want to know how they can tell what’s true. If the factualists, as you call them, write like fiction writers, and the fiction writers write like historians, who’s to say what’s true anymore? I say truth remains debatable no matter what happens to literary form. Truth is never automatically supplied by genre.

Doctorow: When you acknowledge the confusion of genres you are advancing the cause of truth, aren’t you, by pointing to the fact that reality is amenable to any construction that’s placed upon it. This demands as many witnesses as we can possibly muster — what I call multiplicity of witness — so that reality can be arrived at through a common wisdom, through a competitiveness of witness.

The real danger is when certain kinds of witness are authorized and credited and others are not. That’s why writers, why any artists, independent, theoretically, of any kind of institution, are to be valued as a force countervailing the media, the corporation or religious dogma. Whatever the prevailing authorities, it’s important there be enough other voices and perceptions to get us closer to whatever the truth might be.

So to point out the creativity in historiography, or the fantasy elements in some religious observance, is to make things more possibly true than they had been. It’s when people believe too thoroughly in one genre and discredit another that they’re really hurting the possibilities of arriving at the truth.

Arts Fuse: The Waterworks is as much about storytelling as anything else. It’s written by a journalist. It’s about both the curative powers of narrative and the problems inherent in it.

Doctorow: The book was not possible to write until I found McIlvaine’s voice. As I went along I realized he was a journalist who had been reduced to art, as it were, because he didn’t write the story at the time. And now that he’s waited thirty years and has finally decided to unburden himself, he’s subject to the fallibility of his old age, the failure of memory and recollection, the fact that he’s been so obsessed with this material it functions in his dream structure.

Arts Fuse: So he gives you grounds to disbelieve every word.

Doctorow: He’s saying I could be crazy, I’m not asking you to believe me.

When he says, you people with your phones, motorcars, and electric lights, it places him around 1905, 1906. He’s sitting in a dusty apartment, an old man’s apartment, Gramercy Park, and he has a captive audience, the stenographer he dictates to. Having waited this long, the marvelous presumption of the journalist that there are facts to be discovered and printed and revealed in black and white can’t be accommodated any more. McIlvaine can’t quite believe it himself, which may be why he didn’t write the story in the first place, though he supplies a few reasons.

It made me laugh. It made me say, “McIlvaine, you’ve been reduced to art.”

Arts Fuse: He does, early on, say the journalism of his day had not yet made such a “sanctimonious thing of objectivity,” and that objectivity was “finally a way of constructing an opinion for the reader without letting him know that you are.”

Doctorow: I’ve read newspapers of the time and they were all heavily opinionated. You knew exactly where the reporter stood. But the point is there were lots of newspapers.

It was key for me to look at microfilm to see how front pages looked in those days. There were no pictures. There were no banner heads. Nothing went across two columns. The heads were always in single columns, and several subheads, and then the story. And if it was a major story it went up to the next column.

So McIlvaine — this is the way a book gives you gifts, you cannot anticipate something like this — realizes the seven ascending columns of the front page are in effect a metaphor for the separate stories he’s covering. They are, in fact, one story, in the sense that all the stories on a front page belong to each other in a revelation that allows you to understand a society functioning according to its nature in every way simultaneously.

That was one of the happiest days I had writing this book, finding McIlvaine finding his metaphor for what he was slowly discovering as he went on looking for Martin. Although he doesn’t say it, the headline becomes the revelation. When all the stories are completed, the banner headline shows they are one.

Arts Fuse: The Waterworks alludes to all sorts of plots and characters and bits and pieces of popular culture.

Doctorow: If you are talking about Sartorius, there have been references made to Thomas Carlyle’s Sartor Resartus, to a Christopher Isherwood character with a similar name, and to Faulkner’s Sartoris. But I did not mean to gloss or echo any of these things. Sartorius is Latin for tailor, though I didn’t realize that when I chose the name. I chose it because when I was in Germany on a reading tour for Billy Bathgate, I met a rather impressive man, a literary critic and scholar named Sartorius, and really liked the name. It’s that simpleminded. It just had a certain value for me.

The fact that Sartorius means tailor could be meaningful. But these are connections for critics and readers to make. You can’t think about it, you don’t think about it, when you’re writing. As for the use of popular culture, I’ve always done that. My first novel, Welcome to Hard Times, is a Western. It came about because I was working for a film company and had to read Westerns and Western screenplays to advise producers whether there was a movie in the material. I hated the job. I never even liked Westerns as a kid. At a certain point I realized I could lie about the West better than any of these people could do it.

And I realized the value of dealing with a disreputable genre. A certain liberation is possible; you can write in counterpoint to the reader’s expectations. And disreputable genres like the Western were significant because they actually embody national values. When people ask how I became interested in history, I answer it was through an interest in popular culture and disreputable genres. I didn’t think of myself as dealing with history so much as with myth.

At a certain point in The Waterworks I realized I was participating in the nineteenth century tale. That made me very, very happy. I was not writing a documentary novel; I was not using the techniques of the realist in amassing endless documentation. I was writing according to Hawthorne’s definition of the romance, where life is tuned up a little more than usual and you’re writing about the past.

Then suddenly I was seeing New York from a nineteenth century point of view. I’d walk in neighborhoods where so much of the nineteenth-century is still visible. One night a fog came down and covered the whole city except for the nineteenth-century; the skyscrapers were all gone. And I walked around and said this was Melville’s town. And this was what Poe saw when he was sober. And I was in the nineteenth-century brushing against the scientists — then called natural scientists, metaphysicians of science — touching on everyone from Dr. Frankenstein to H.G. Wells’ Dr. Moreau.

Arts Fuse: As in The Island of Dr. Moreau.

Doctorow: Yes, but you don’t feel you merely participate in a convention if you add to it, and it’s my arrogant feeling that I’ve added to it. You may disagree.

Arts Fuse: No, I think the book works. But I think it’s sometimes a close shave.

Doctorow: You can’t write anything unless you take risks. You can’t expect to accomplish anything if you’re going to be safe.

Arts Fuse: Sartorius is in some ways the a superman, isn’t he? None of the natural limitations apply to him.

Doctorow: He’s in his own universe. I think McIlvaine says — or it was Martin Pemberton? — that Sartorius was the kind of man for whom life seemed to exist for the sake of his engagement with it. That’s the key description.

Arts Fuse: He’s a creature completely given to reason.

Doctorow: It’s an idea that first pops up in The Lives of the Poets. In a novella in that book a writer is talking about men of supreme intellectual gifts whose mind takes them through a passage of great glory and honor as they make genuine contributions to their field. But then they keep going until they project themselves outside anything society can sustain or tolerate.

For instance, I see the figure of Wilhelm Reich that way. In my opinion, he was second only to Freud in the early days of psychoanalysis. He was spectacular but always troublesome, always difficult. He kept going, always being Reich, until he ends up with the orgone box, and, in the last days of his life, shoots down UFOS with tin cans. He was the same man, always.

Similarly, Sartorius. He had a great career as a surgeon. He’s a real healer and innovator. He finds procedures to save limbs, participates in the Sanitary Commission and helps prevent a major cholera outbreak in the 1870s. He intuits the nature of the cholera organism, the cause of cholera. All this is to the good; but he keeps going, you see, he keeps going.

The point of the whole city and its life, then as probably now, is that energy radiates out in all directions. The same energies, essentially amoral, produce high-speed rotary presses to turn out newspapers to be distributed for a penny or two on the street by vagrant children. There’s a relationship between the hi-tech railroads and the telegraphy and the genius of the times and the detritus of the times. It’s all the same thing and Sartorius is part of it.

Someone suggested I name this book Sartorius, and I thought about it and said no, it’s about more than Sartorius. It’s about the entire society, about the society of the city seen as a character. Whether it’s politics or intellectual achievements like those of Sartorius or the newspaper business or vagrant children in the streets, it’s the same city. There’s a relationship among all these things. You don’t have one without the other.

Arts Fuse: There is corruption above ground with Boss Tweed at the apex. There is the necropolis you allude to in one lovely image — “The cookstoves in our homes burned coal, and on a winter morning without wind, black plumes rose from the chimneys in orderly rows, like the shimmering citizens of a necropolis.” The necropolis is headed by Sartorius. Still, Sartorius is not easy to judge. Your characters have all sorts of debates about him. And he’s not easy for us to judge because it feels as if he is contemporary. Judging him is judging ourselves.

Doctorow: You can’t think this way when you’re writing the book because you’re in the sentences and you’re living with these people. At one point, McIlvaine talks about the elusiveness of villainy. And if you think about it, all the villains are for the most part off stage. One of the chances I took is to have a book full of villains none of whom are really present.

Arts Fuse: Sartorius is not around much more than Boss Tweed himself.

Doctorow: Tweed is more an ethos of the city. You get one glimpse of him at the beginning and one at the end. And old Pemberton is not there, except by hearsay, until the end when he’s dead. Eustace Simmins is found dead.

That’s why I say McIlvaine is reduced to art. He’s getting all his stuff second or third-hand. And the one villain physically present is intellectually absent; he’s elusive by virtue of his own point of view and the fact that he cannot accept the standards society wants to apply to him.

Arts Fuse: It’s interesting to think of most events in The Waterworks as occurring offstage.

Doctorow: Everything does. We’re getting it first of all through this man and his memory. He’s reporting conversations at great length that occurred a long time ago, and reporting based on the testimony, the witnessing, of other people. There’s very little that he sees himself. He hears so much through other voices. That’s one of the things I like about the composition. That’s why I say he’s reduced to art.

Arts Fuse: There are invisible threads of connection between Boss Tweed and Sartorius, the aboveground and the underground, so to speak. But there’s another sense in which it’s Sartorius and Grimshaw who resemble each other. These are the two characters for whom certainties exist — who refuse narrative, who will not be reduced to art.

Doctorow: It’s interesting. I like that.

Arts Fuse: There are writers who subvert genre and say, well, I just do it. They refuse to reflect about it. You not only do it but are in the forefront of reflection on it.

Doctorow: I understand those writers — you do just do it. These reflections and insights are stimulated by questions like yours. For instance, I used to know a lot more about writing than I do now. I used to know a lot about writing. And now I just do it.

I’ve incorporated all that knowledge and now it’s something I just work out of so I don’t see it anymore. It’s something I’m inside of, or it’s inside me. When writer’s say that, that’s what they are talking about.

Arts Fuse: You have said that anyone who watches television understands discontinuity. You don’t have to explain everything. And you can apply this to the novel.

Ragtime does that; Ragtime does all this marvelous editing and cutting and then the movie is slow and a little suffocating. It seemed exactly the wrong pace to use for Ragtime. I mean Ragtime was a movie, your book worked like a movie. And the movie worked like a book.

Doctorow: That’s funny. I like that. Everybody says my books are cinematic, except the directors. They don’t say that. They say they are hard to translate. And it’s true, there’s a lot of interior moral action coming from the voices of the narrators. I throw my voice, like a ventriloquist, and that provides a kind of interior action that is difficult for the script to achieve.

Arts Fuse: I’ve heard you are doing a cable channel of literature.

Doctorow: I’ve talked to a few people who liked the idea and have hopes it will be on the air next year. We want to get cable channel time devoted exclusively to books and authors, point being to give books their full discourse and not to turn it into television. We want to have readings and discussions and critiques and reviews and reports and a number of different formats but all for the presentation of the word.

Harvey Blume is an author — Ota Benga: The Pygmy At The Zoo — who has published essays, reviews, and interviews widely, in The New York Times, Boston Globe, Agni, The American Prospect, and The Forward, among other venues. His blog in progress, which will archive that material and be a platform for new, is here. He contributes regularly to The Arts Fuse and wants to help it continue to grow into a critical voice to be reckoned with.

I can’t resist posting one of my favorite bits of E. L. Doctorow. It is from Billy Bathgate, when Dutch Schultz announces to his crew that he has decided to convert from Judaism to Catholicism:

“I get a good feeling every time I walk in there, I don’t understand Latin, but I don’t understand Hebrew neither, so why not both, is there a law against both? Christ was both, for christsake, what’s the big deal. They push confession, I can’t pretend I’m wild abut that, no offense, But I’ll deal with it when the time comes. This mustn’t get to my mother – Irving, your mother neither, the mothers shouldn’t know this, they wouldn’t understand. I never liked the old men davening in the synagogue, rocking swaying back and forth, everyone mumbling to himself at his own speed, the head going up and down the shoulders rocking, I like a little dignity, I like everyone singing something together, everyone doing the same thing at the same time, I like the order of that, it means something everyone goes down on their knees the same time, it puts light on God, is this too deep for you, Lulu? Look at that, he is so unhappy, Otto, look at his expression he’s gonna cry, tell him I’m still the Dutchman, tell him nothing is changed, nothing is changed, you dumb Hebe!”

[The aforementioned Irving, however, is troubled.]

“I am not a religious man myself,” Irving said, “but the way they nod and bow and don’t keep still a minute, there’s a very reasonable explanation for that. It’s the way it is with candles, the old men praying in the synagogue are the flames of candles that sway back and forth leaning one way and another way, every one of them nodding and bowing like a little candle flame. That’s the little light of the soul, which of course is always in danger of blowing out. So that’s what that is all about,” Irving said.

. . .

“But Dutch wouldn’t know that. All he knows is it bothers him,” Irving said in his quiet voice.

Great quote. It really highlights the great writer that Doctorow was. And funny too.