Book Commentary: Two Cheers for British Poet, Book Artist, and Visionary William Blake

Susanne M. Sklar’s study is the best exploration of William Blake’s miraculously bewildering masterpiece that I know of—thoughtful, scholarly, imaginative, and supremely sympathetic to the poet’s ornery complexity as well as his capacity to inspire wonder.

By Bill Marx

I can’t let National Poetry Month go by without reporting some welcome news about one of my favorite poets and artists—the English visionary William Blake (1757–1827). First, overlooked examples of his pictorial art have recently come to light. Earlier this year, the University of Manchester announced that its current exhibition on William Blake (Burning Bright: William Blake and Art of the Book , through June 23) would feature a selection of the approximately 350 engraved plates discovered in the John Rylands Library. Students, under the guidance of Blake expert Colin Trodd, spent the past two years authenticating the find. The library owns a number of Blake’s works—including hand-colored illustrations of Young’s Night Thoughts—and suspected that there were others tucked away in its massive collection of over a million books.

Blake was dead set against the exploitation of commercial engraving work, for which he was often badly paid. Peter Ackroyd’s biography explores Blake’s complaints about the homogenization of art:

In an age that was becoming increasingly uniform and standardized, he [Blake] tried to affirm the originality of artistic genius. He realized that, if the division between invention and execution is made, an ‘Idea’ or ‘Design’ can be simply produced on an assembly line. Art then is turned into a ‘Good for Nothing Commodity’ manufactured by ‘Ignorant Journeymen’ for a society of equally ignorant consumers. It becomes part of that ‘destructive Machine’ into which all life is presumably being turned—”A machine is not a Man nor a Work of Art it is destructive of Humanity & of Art.’

Ackroyd goes on to point out how Blake connected the routinization of creativity to the homogenization of culture and society: “None of them {critics of art} had taken their analysis as far, or as deep, as Blake. It is yet another example of his clairvoyant understanding of his age that he is able to draw the connection between art, industrial economics, and what would become the ‘consumer societies’ of modern civilization in an analysis that was not otherwise formulated until the present century.”

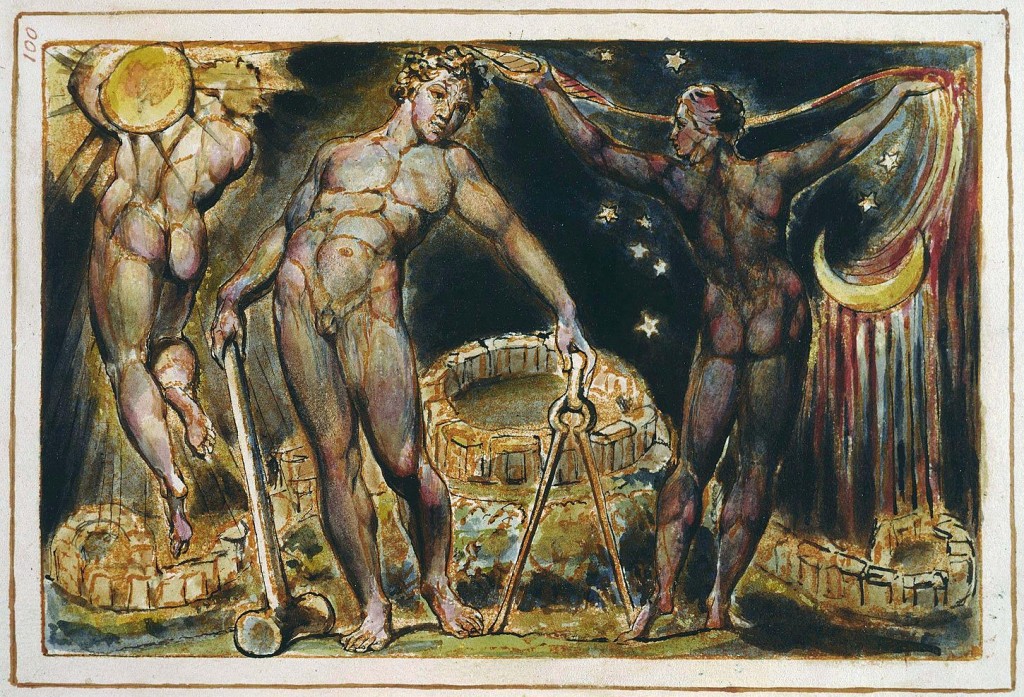

Blake was far more interested in creating original engravings for his masterful book art, volumes made up of his glorious illustrations and mythopoetic poetry. Many are familiar with his exquisite Songs of Innocence and Experience, but few know the glories of his later “prophetic books” such as Milton and Jerusalem: The Emanation of the Giant Albion, which present to us his mind-expanding visual and poetic genius at full-mad-throttle. These are difficult poems, expansive graphic novels (in the best sense) that resist easy comprehension because Blake creates his own formidably eccentric model of spiritual and imaginative development on a cosmic scale.

For those who want to venture forth into Blake’s obscurer realms of revelation, there is now a terrific guide, at least to Jerusalem (created between 1804 and 1820). Susanne M. Sklar’s Blake’s Jerusalem as Visionary Theatre: Entering the Divine Body (Oxford University Press) is the best analysis/interpretation of the miraculously bewildering masterpiece that I know of—thoughtful, scholarly, imaginative, and supremely sympathetic to Blake’s ornery complexity as well as his capacity to engender wonder.

Sklar worked to make sense of what some consider to be an “unreadable” poem after “two busy decades of working as an actress and director, a college teacher, a social worker, and a peace activist and researcher.” She is currently a member of the Cummor Fellowship, Oxford, and an assistant professor in English and Great Ideas at Carthage College in Kenosha, Wisconsin. There’s an informative interview with this unusual scholar about Blake’s Jerusalem as Visionary Theatre as part of her mission (she calls it a “vocation”) to understand the life and mind of William Blake on an episode of Here on Earth, a program on Wisconsin Public Radio.

Sklar’s flexible critical approach emphasizes the poem’s power as a multivalent dramatic spectacle.

Jerusalem‘s words and images seek to move us (with its characters) away from a purely rational way of seeing and living to one that is highly imaginative. Jerusalem is not a poem to which we assign ‘meaning’; it is meant to be experienced. It does not progress in a linear fashion: people and places morph into one another; the story unfolds kaleidoscopically, a changing montage of words and images. This changing montage is full of treasures when we engage with it imaginatively; it does not respond to a solely intellectual approach.

Sklar insists that Jerusalem is not a puzzle to be solved but a theatrical journey filled with mysterious figures to be relished. Blake believed that “what is not too Explicit’ is ‘the fittest for Instruction because it rouzes the facilities to act.” He demands an active engagement of the reader’s reason, emotions, and imagination. Sometimes Blake’s Jerusalem as Visionary Theatre forsakes its experiential approach and treats the poem as a cryptic code to be broken. But generally, Sklar draws superbly on her background as an actress—she appreciates the dense fantastical gusto of the poet’s stagy apocalyptic vision, using the genre of “visionary theatre” as a speculative tool to illuminate a poem where

the text and the reader are not confined by mundane space and time; action can take place both within the microcosm (‘little world’) of an individual mind or soul and the macrocosm (‘great world’) of politics, ecology, and the body of God. The ‘stage’ is within, around, and before us — and on that micro- and macrocosmic stage, the human, the angelic, and the divine interrelate. Imaginatively, we can think of ourselves as being as fluid as Blake’s peculiar characters. We can ‘enter into’ them imaginatively, as an actor would do — and we can be transformed by them. This is in keeping with the purpose of the poem; Blake wants to open our eyes ‘into Eternity … in the Bosom of God, the Human Imagination’: he wants us to dwell with and in his characters, with one another — and with God.

This is brilliant way into the genius of Blake’s work. And the rigors of taking the trip “into Eternity,” difficult as it is, are well worth the effort. Sklar gives readers a great gift: an opportunity to zip comfortably round and about the astonishing consciousness of a poet/artist who created such beautiful engraved plates as the one below from Jerusalem.