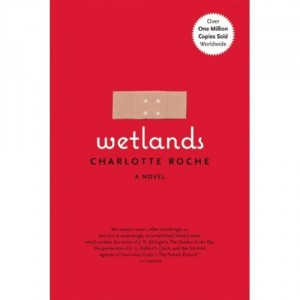

Book Review: Charlotte Roche’s”Wetlands” — Ick. Just Ick.

Charlotte Roche is one of the most famous authors in Germany. Thomas Mann must be spinning in his grave.

Wetlands By Charlotte Roche. Translated from the German by Tim Mohr. Grove Press, 240 pages.

By Tommy Wallach

On the subject of literary criticism, Martin Amis has written that “quotation is the reviewer’s only hard evidence.” But I’m going to quote Wetlands sparingly in this review. And that’s for your sake. I could explain why myself, but it’s probably more efficient for me to give you a sample: “I also love it when someone goes down on me while I’m bleeding. It’s kind of a test of mettle for the guy. When he’s finished licking and looks up with his blood-smeared mouth, I kiss him so we both look like wolves who’ve just ripped open a deer.”

Yep. I know. Yuck. (Just be glad you’re not Tim Mohr, the translator, who probably had to read that 15 times in the German, then try it out five or six different ways in English. Kudos, Mr. Mohr).

But let’s not be premature. After all, were not James Joyce and Vladimir Nabokov both decried as pornographers in their time? Is not a single photograph by Robert Mapplethorpe likely to prove more viscerally disgusting than even the naughtiest bunch of words? Do not the films of Catherine Breillat receive critical plaudits, even though they invariably feature graphic sex and violence? As a fan of all the artists mentioned above, I would never knock something just for grossing me out. Important work is important work, whether it turns the stomach or not.

Yet my response remains: yuck.

Wetlands is the story of 18 year-old Helen, an unapologetic sex-maniac who is laid out in the proctology unit of a hospital for the entirety of the novel. Her injury relates to a shaving accident about which the less said the better. Over the course of a couple hundred pages, we are granted a close-up look at every part of Helen’s anatomy, but very little in the way of her character. Her parents are split up, and though she says time and again that she wants to get them back together, the reasons for this are never fully explained. Why did they divorce? Are they still in love? Do they love their new partners (alluded to but never described)? Helen doesn’t care. She doesn’t even know what her parents do for a living. Fine for her, but this reader would have preferred a little context.

The emotional hinge of the book is meant to be the revelation that Helen once came home to find her mother and brother passed out on sleeping pills in front of an open gas oven. But any pathos that Roche might have rung from this memory is ruined by her bathetic writing. When Helen tells her brother about the incident (he was too young to remember it), he gives a two-sentence response and leaves. Now, I’m not sure what I would say if I found out my mom had tried to kill both herself and me at the same time, but I’m willing to guess it would be a bit more dramatic than, “That’s why I always have those fucked-up dreams. She’s going to get hers.”

Wetlands is being touted as a novel of feminist liberation, but it ends up saying a lot less about gender than it does about mental illness (one reviewer compared it to Plath’s The Bell Jar, which is apt). Unfortunately, I don’t think Roche planned this. In interviews, the 30 year old ex-TV personality has said that her book was inspired by the wall of feminine hygiene products on offer at her local pharmacy. This isn’t surprising, as Wetlands reads far more like a polemic than like a novel. In a pinch, it might do for the syllabus of a Gender Studies or Psych class, but it hardly qualifies as literature.

Tagged: Books, Charlotte-Roche, Featured, Grove-Press, Tim-Mohr, Tommy-Wallach, Wetlands