Theater Review: Ayckbourn’s Comedy of Desire

Boredom is the root of all evil . . . The influence that it exerts is altogether magical, except that it is not the influence of attraction, but of repulsion. — Søren Kierkegaard, “Either/Or”

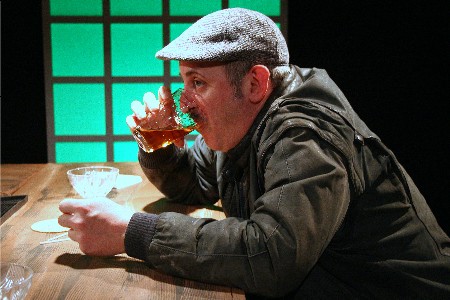

Dan (Michael Steven Costello) tries to drink the pain away in In Private Fears in Public Places. Photo by Richard Hall/Silverline Images

Private Fears in Public Places by Alan Ayckbourn. Directed by David J. Miller. Set design by Miller. Staged by the Zeitgeist Stage Company at the Boston Center for the Arts, Boston, MA, through March 6.

Reviewed by Bill Marx

Alan Ayckbourn is a playwright who has grown on me by growing out of himself. At least his most recent plays, such as 2004’s Private Fears in Public Places, represent a refreshingly haikuesque departure from the intricately constructed, large scale semi-farces he is most identified with, such as The Norman Conquests and House & Garden.

Popular as these shows have been here and aboard, they have always struck me, despite their ambition, as thin comic gruel, partly because they fall somewhere in-between farce and sit-com. Private Fears suggests Ayckbourn has left that unsatisfying comic netherworld (perhaps after 70 scripts he has finally exhausted it) and is writing plays that, to their credit, fit neither category.

(Granted, Ayckbourn has stretched his imagination in various ways throughout his long career, from the dank brew of blackmail, murder, and drugs in A Small Family Business to the feminist schizophrenia at the center of Woman in Mind and the futuristic sci-fi of Henceforward . . .)

Judging by Private Fears, Ayckbourn has developed into a mature observer of human disconnection, a comic diagnostician of boredom. I say boredom because a line in the play got me thinking about what makes Ayckbourn’s characters come together and then draw apart. One of the women in the play observes with conviction that she bores herself as well as others. That struck me as a particularly revealing confession about what Ayckbourn is up to now—he lets his figures curdle in the world they create for themselves rather than surrounding them with whiz-bang formal contrivances.

In his earlier plays, Ayckbourn drops his characters into a whirligig comic plot even though his men and women lack the fierce desires for sex and respectability that propel the best examples of slammed-door farce. The hyper-combustibility of free-wheeling desire and the need to maintain an untarnished reputation fuels this kind of extreme comedy: a genius like Ben Jonson takes that conflict further, exploring our fetish for desire itself, the addictive pleasures of wanting to want.

But Ayckbourn’s characters don’t seem very interested in sexuality or power; they are closer to cartoonish sit-com characters, whose mild appetites and vapid dreams are meant to be aroused and satisfied in 30 minutes. In his most popular plays, Ayckbourn plunks his soft-headed, bumbling creatures into the manic machinery of farce—and it amusingly chews them up.

In Private Fears the playwright forgoes the customary armor of ingenuity he builds around his characters, letting us look more closely at the poignant comedy created by people whose isolation appears to be mostly self-generated—they are bored with themselves and thus bore others. At least a self-damning acedia is a plausible (and intriguing) explanation for the play’s touching roundelay of relationship misfires.

Christine Power and Michael Steven Costello in Zeitgeist Stage Company’s production of Private Fears in Public Places. Photo by Richard Hall/Silverline Images

Written in 54 cinematic scenes (the script was made into a fine 2006 film by French director Alan Resnais), the play’s ostensible center is the crumbling relationship of Nicola (Christine Power), a young woman looking for a three bedroom apartment for herself and her husband-to-be, Dan (Michael Steven Costello), an ex-army officer who is determined to remain unemployed. Nicole deals with an inadequate real estate agent Stewart (Robert Bonotto), who finds, to his surprise, that the hardcore Christianity professed by his attractive, young co-worker, Charlotte (Becca A. Lewis), may only be skin deep.

Meanwhile, Charlotte is temporarily looking after the randy and foul-mouthed father (the character remains offstage) of Ambrose (Bill Salem), Dan’s favorite bartender, the friendly but ineffective ear for his customer’s soused self-justifications and trivial complaints. Stewart’s middle-aged sister, Imogen (Shelley Brown), lies to her bro about cruising the bars, fruitlessly, for love.

The Zeitgeist Stage Company production is sensitively directed by David Miller, who generally pulls sturdy performances from his cast. As Dan, Michael Steven Costello could do more to show the flickers of panic behind Dan’s bluster. While compelling, the performer sometimes leans too hard into the character’s faux-bravado.

Becca A. Lewis is impishly amusing as Charlotte, the fundamentalist tease; Robert Bonotto provides nimble deadpan as Stewart, particularly through the weird twists and turns of Charlotte’s temptations. Power and Salem get at the anguished power of their humane characters, the only figures in the play who directly convey a sense of loss.

Charlotte is the play’s duplicitous Eve, a game player who amuses and/or punishes herself by inviting lonely men to contemplate their null state. At one point Ambrose, after taking a gander at the Charlotte’s Bible, gently complains about how harsh the Old Testament is. The script’s satiric treatment of religion—how in Charlotte’s hands it doesn’t give comfort but aids and abets despair—suggests that Ayckbourn is taking aim at more than romantic disconnection, but poking at something closer to the spiritual bone.

Pascal defines boredom as “nullity without realizing it.” Ayckbourn has come up with a mordant comedy rooted in his ironic strengths as a playwright—Private Fears depends on the surfeit, rather than the excess, of desire.

.

Tagged: Alan Ayckbourn, Boston, English, Private Fears in Public Places, Theater, comedy