Book Review: “When Caesar Was King” — How Sid Caesar Reinvented American Comedy

By Thomas Connolly

The book argues, convincingly, that Sid Caesar’s genius wasn’t in what he did or said so much as in the anarchistic energy he encouraged his writers to unleash and harness.

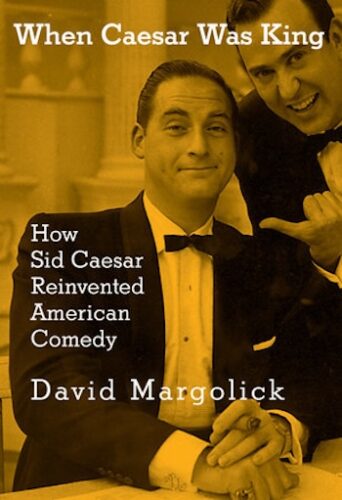

When Caesar Was King: How Sid Caesar Reinvented American Comedy by David Margolick. Schocken Books, 400 pages, $35

When Caesar Was King is more than the story of Sid Caesar and the writers’ regiment he gathered and commanded that revolutionized American sketch comedy. It is a multi-layered examination of how comedy and culture collided in the 1950s. Caesar’s style for getting a laugh was to spray a magnum of champagne rather than a seltzer bottle — it was a quiche in the face, not a pie. Slapstick, yes, but with an accent on angst. Margolick is in on Caesar’s secret, and he brilliantly dissects how what became a TV era of sublime farce was created, in the process revealing that the head man himself was a blank slate, a comic catalyst. Yet Caesar sparked a battery of the most gifted ensemble of writers ever jammed together in a pastrami-strewn room.

When Caesar Was King is more than the story of Sid Caesar and the writers’ regiment he gathered and commanded that revolutionized American sketch comedy. It is a multi-layered examination of how comedy and culture collided in the 1950s. Caesar’s style for getting a laugh was to spray a magnum of champagne rather than a seltzer bottle — it was a quiche in the face, not a pie. Slapstick, yes, but with an accent on angst. Margolick is in on Caesar’s secret, and he brilliantly dissects how what became a TV era of sublime farce was created, in the process revealing that the head man himself was a blank slate, a comic catalyst. Yet Caesar sparked a battery of the most gifted ensemble of writers ever jammed together in a pastrami-strewn room.

Margolick’s book cuts through the nostalgia and legendifying that sugar-coat or, at its worse, homogenize the inspired comic frenzy that produced The Admiral Broadway Revue, Your Show of Shows, and Caesar’s Hour. Neil Simon wrote a play and a TV movie about his experiences working on these programs. Carl Reiner created The Dick Van Dyke Show, a wholesome version of the Caesar’s writers’ room. My Favorite Year, featuring Caesar doppelgänger “King Kaiser,” was produced by Caesar acolyte and lifelong worshipper, Mel Brooks. Woody Allen was in that room too; he’s never written about Caesar directly, but has often acknowledged his debt to him. His screenplay for Bullets Over Broadway was inspired by a Caesar sketch of the same name. The tributes to Caesar started right after his show was cancelled, and they have never stopped. Caesar’s TV reign lasted for seven years but, for over half a century afterwards, his career sadly sputtered.

Margolick’s cold, analytic eye is vital for understanding the reasons behind Caesar’s decline and fall. It’s painful to admit but, if you look at the numbers, it’s clear why he virtually disappeared from television. His show was only a major hit in its first three seasons. The fact is, Caesar never had mass appeal. In 1949, Caesar’s first show, sponsored by Admiral (the television set manufacturer), was credited with increasing its sponsor’s sales from 500 to 10,000 sets weekly. Yet, in a bizarre corporate move, the show was cancelled because Admiral decided the program was too costly. (It would be better to invest in its factories instead.) Nevertheless, producer Max Liebman (“the man who invented Sid Caesar”) repackaged the program with the star and his indispensable partner, Imogene Coca, in Your Show of Shows Your Show of Shows. In 1950, there were televisions in only 9% of America’s living rooms; three years later, 45% of homes had them, and Your Show of Shows had dropped out of the Nielsen top twenty-five.

Nevertheless, Caesar and Coca were still considered a hit team. NBC figured if they split them up, they would have two successful shows. It didn’t work out that way. Margolick argues that Caesar was never the same, and even though Caesar’s Hour contained some great sketches, Your Show of Shows is inevitably the most fervently recalled. Margolick credits the visceral connection between Caesar and Coca. Off camera, they had absolutely nothing to say to each other; one barely even acknowledged the other. But, once it was show time, they were explosively combustible. Along with Coca, Carl Reiner proved to be the perfect straight man as well as a gifted double-talker. Howard Morris, Caesar’s inimitable diminutive foil and virtually a physical prop, completed the quartet. Coca, who had almost no personal interaction with Caesar, always expressed the warmest regard for him. Margolick hints that Reiner may have had an ambiguous attitude toward the star, but he makes it clear that Morris felt trapped by his continual association with Caesar, feeling that it limited his career. Still, all of them were always willing to work with him again.

If you’ve only seen the various compilations of sketches from Caesar’s TV programs, you only have scant idea of the range of their content. They were highbrow variety revues. Almost every week, opera stars were invited to sing; sophisticated dance numbers punctuated the comedy. Many of Caesar’s most famous sketches were inspired by foreign films, such as Ugetsu or The Last Laugh. One of Caesar’s greatest bits takes off on Pagliacci’s “Vesti la giubba,” during which he improvises a tic-tac-toe make-up moment.

The usual explanations for Caesar’s fifty-year career slump are burnout and alcohol, accented by pill addictions and depression. Margolick’s subtle analysis of Caesar’s personality versus his persona renders these conventional justifications superficial, though still somewhat accurate. The cri de coeur from all of Caesar’s collaborators was: Why is there no place for Sid Caesar’s genius? The comedian’s first autobiography was even entitled Where Have I Been? Margolick’s book points out that Caesar’s career was headed nowhere, even as his show was winning multiple Emmys and critical huzzahs. The truth is, Caesar’s popularity was a fluke. His success was part of the first golden age of television. The same change in the zeitgeist that rejected Playhouse 90 spurned Caesar’s highfalutin’ double-talking “Professor” character. Explaining the fall from grace isn’t rocket science: the rival who drove Caesar off the air was inane bandleader Lawrence Welk. Jejune tunes trumped edgy satire. Ironically, Welk spoke with a thick German accent, one of Caesar’s prominent shticks.

Imogene Coca and Caesar in Your Show of Shows (1952). Photo: WikiMedia

Margolick notes that Caesar was only popular in urban markets. In the hinterlands, viewers not only changed the channel, they fired off letters to local newspapers and the network bitterly complaining that Caesar must be taken off the air because he thought he was better than they were. The thinly veiled or in some cases open, anti-semitism of Caesar’s haters is a significant characteristic. Caesar and his writers were, of course, all Jewish, and most of them were steeped in Jewish bourgeois culture. (Mel Brooks wasn’t, but Mel Tolkin, the head writer, immersed Brooks in its byways as soon as he could). Engaging in cultural subterfuge, the comedians peppered the double-talk sketches with Yiddish. No overtly Jewish characters or themes were alluded to in the scripts, but the material’s sensibilities were clear. Middle America would have no truck with even a hint of Mitteleuropa.

Be that as it may, those writers had the last laugh. Caesar himself may have broken down, but the comic machine his writers engineered was just getting started. There is almost no major television or movie comedy of the last seven decades that hasn’t been influenced by Caesar’s writers. Not to mention Broadway, what with playwright Neil Simon’s quarter-century of hits. This is not to belittle Caesar—he was a genius. The kingpin’s writers obsessed over him. Margolick reports that they spent almost all their free time “trying to figure out what made their inspirational taskmaster tick. Not only that, Caesar was also one of the greatest improvisers of all time. (His Pagliacci tic-tac-toe bit wasn’t in the script.)

Margolick takes you into that writer’s room, deftly putting Caesar at its center, so that you can see how he wasn’t quite there. The author admires his subject, but doesn’t like him. Caesar was all temperament — yet seemed to have had no emotions. Despite his name, he was more of a sphinx than a Caesar. Caesar’s writers, Mel Tolkin, Lucille Kallen, Michael Stewart, Selma Diamond, the Simon brothers, Brooks, Allen, Reiner, et al., launched their careers from the laughter the Sid Caesar years of tsuris inspired, but the man himself remained an enigma, even to his disciples. When Caesar Was King argues, convincingly, that Caesar’s genius wasn’t in what he did or said so much as in the anarchistic energy he encouraged his writers to unleash and harness. Margolick admires the King and his court, but sees the tragedy clearly: Caesar was the instigator of a cultural revolution he didn’t quite understand and couldn’t survive.

Tom Connolly is Professor Emeritus of Humanities and Social Sciences at Prince Mohammad Bin Fahd University. He recently edited a historical study (in English) of the 19th- and 20th-century Jewish community of Döbling for the Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Institut für Kulturwissenschaften. His book Goodbye, Good Ol’ USA: What America Lost in World War II: The Movies, The Home Front and Postwar Culture is forthcoming from Houghton Mifflin/PMU Press.

I agree with you that Caesar the person is an enormous enigma, something essential missing and empty at the core, the same as later with another comic chameleon, Peter Sellers. Was there really anti-Semitism aimed at the program? I doubt that the audience knew that all the writers were Jewish or noted the Yiddishisms thrown into the dialogue. Yes, Imogen Coca was great but I’d like to note that her replacement, Nanette Fabray, was also excellent, her comic genius spilling over from SINGIN’ IN THE RAIN. Howard Morris was “virtually a physical prop.” I wish I’d said that.