Book Review: “Ethel Barrymore” — A Reliable Itinerary, but the Bio Misses the Journey

By Tom Connolly

This biography of Ethel Barrymore briskly traces her mythic career, but brings to life neither the woman nor her theatre.

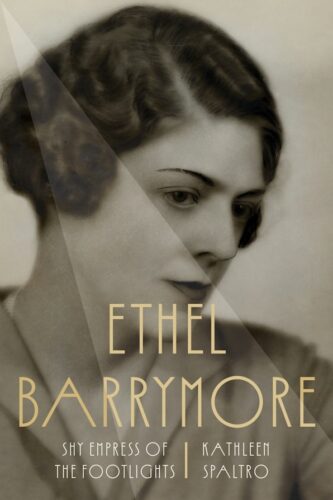

Ethel Barrymore: Shy Empress of the Footlights by Kathleen Spaltro. University Press of Kentucky, 312 pages, $40.

Kathleen Spaltro’s contradictory title reveals the problem at the heart of this biography. Ethel Barrymore reigned over the stage and screen for over seventy years, but she kept her true self far offstage. The actress insisted that the distance she put between herself and her roles are what made her successful performances possible. (She would have suggested straightjackets for the likes of Daniel Day-Lewis and Christian Bale). On the one hand, Spaltro has assiduously assembled the facts of Barrymore’s life. The chronology is straightforward, the documentation comprehensive. What the book fails to do is make Barrymore live on the page, to evoke the stage that she commanded for so long, or explain why we should care about a career reduced to names, dates, and critics’ quotes.

Spaltro’s biography of Mary Astor drew on primary sources to debunk myths which helped to restore some of the fallen star’s luster. Her recent book on Lionel Barrymore proved she knows her Barrymores. But, like this biography of Ethel, the volume suffers from being more of a résumé than a life story. We applaud Ethel’s star turn but she never shows up for the curtain call.

Spaltro focuses on the burden that Ethel’s predetermined destiny placed on her, beginning with her birth in 1879 into theatrical royalty as the granddaughter of the formidable Louisa Lane Drew. Ethel was the daughter of the dissolute matinee idol Maurice Barrymore and the sparkling comedienne Georgiana Drew Barrymore. The majestic figure of Ethel’s grandmother weighed heavily on her throughout her life; Louisa drilled into Ethel the iron discipline required by the theatre, and living up to the demands made by that devotion became a cross to bear.

During her brief childhood, while her parents toured, Ethel shuttled between convent schools and relatives. The nuns encouraged her musical talent and sparked a devout Catholicism that she clung to throughout her life. But her mother’s early death and father’s mental incapacity (tertiary syphilis sent him to an asylum after he tried to strangle her) forced Ethel to surrender her dream of becoming a concert pianist and take up the family business. Spaltro details her breakthrough performance in Captain Jinks of the Horse Marines (1901). She became a pop culture phenomenon — “the Ethel Barrymore girl”– an image of what Ethel was expected to be on stage and a model of fashion for young women from London to San Francisco. Men were drawn to the phenomenon. Winston Churchill was among her suitors.

We’re told Ethel rejected Winston Churchill’s marriage proposal because she didn’t want to be a politician’s wife. Spaltro treats this decision as a box to be checked off rather than as an invitation to explore Barrymore’s complicated sense of self. Similarly, we learn little about her troubled marriage to Samuel Colt and even less about her children (who were devoted to her). Barrymore died in 1959; there are no archives to be mined or diaries left behind to illuminate Ethel’s inner life. We do learn that she escaped “the Ethel Barrymore girl” image by performing in plays by Ibsen, Maugham, and, fitfully, Shakespeare. The chapter on her role in founding Actors’ Equity during the 1919 strike is informative, but it’s airless. We learn the facts but never sense what was at stake that made it a landmark labor struggle.

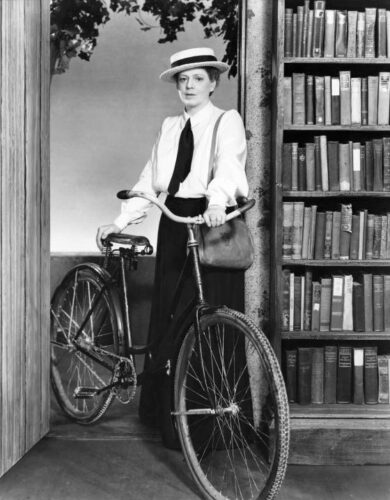

Ethel Barrymore in the original Broadway production of The Corn Is Green (1940). Photo: Wikimedia

The exception in Spaltro’s ‘just the facts’ chronicle is Barrymore’s 1940 renaissance in the Broadway production of The Corn is Green. This is rightly identified as a triumph: the show ran for over a year in New York, toured for years afterward, and returned to Broadway. She performed the play over a thousand times and made a fortune, but, like all the Barrymores, she was terrible with money. Once she aged, she turned to Hollywood. But this extraordinary hit only highlights another unexplored question: why was Barrymore, after decades in the theatre, often so inept at choosing roles for herself? After Corn, her stage career was a series of flops. What accounts for the string of failures? Was it poor judgment, poverty, or something else?

More frustrating is Spaltro’s failure to place Barrymore within the context of her acting contemporaries. What distinguished her work from Katharine Cornell’s passionate intensity, Jane Cowl’s romantic lyricism, Helen Hayes’s technical virtuosity, or Eva Le Gallienne’s aspirational aesthetic? We’re told that Barrymore was great, but not how she differed from the greatness of other stars. Cornell toured constantly, too, but never played so many one-night stands as Barrymore. Was this her strategic way of keeping an edge over Cornell with fans in remote towns, or had Ethel’s reputation for drunken onstage lapses reduced her to such straits? Even so, in 1944, at the height of the war, this headline flashed across Times Square: “GENERAL MACARTHUR LANDS AT LEYTE. ETHEL BARRYMORE’S TEMPERATURE LOWER.”

The book moves onto sounder ground when dealing with Barrymore’s Hollywood years. Spaltro’s discussion of Ethel’s Oscar-winning turn opposite Cary Grant in 1944’s None but the Lonely Heart suggests how Barrymore’s reserve and dignity translated powerfully to film. One observation — that Ethel preferred radio and television to movies because those deadline-driven productions were “sequential, just like stage acting” — offers a window into how she thought about her craft. But even here, the analysis remains surface-level. We learn that Barrymore made films in order to pay bills, that she eventually liked Southern California’s climate, and that her name ensured steady work. What we don’t get is any sense of how she approached a role or why her performances stirred such devotion in generations of fans.

Spaltro’s argument that Barrymore’s career was born from “duty, not desire” is asserted rather than demonstrated. The framework for that reasoning exists: childhood in institutional settings, while parents chased theatrical glory; financial necessity forcing her onto the stage when she wanted to be at the piano; decades of touring to preserve family reputation and income. But duty to what? To her grandmother’s legacy? To absent parents? To some idealized notion of what a Barrymore owed the American theater? The book never attempts to look into what drove Barrymore, emotionally, through decades of a career that she supposedly didn’t want. This matters, because the tension between duty and desire, between the public performance of self and the private withholding of self, is what makes Barrymore an interesting figure. Spaltro identifies the paradox — but never investigates it.

Ethel Barrymore in a scene from 1946’s The Spiral Staircase.

The book’s title promises to illuminate another paradox, the “shy empress.” But, once again, it delivers only the most superficial treatment. We’re told repeatedly about Barrymore’s shyness, her discomfort with celebrity, her preference for privacy. What we don’t get is any sustained exploration of how this allegedly shy woman became the indomitable figure well documented by those who worked with her in later years. The anecdotes are there in the theatrical record: Barrymore’s legendary hauteur, her demands, her ability to freeze out anyone who displeased her, the regal bearing that made directors and co-stars tread warily. On her deathbed, she was read a Variety notice about Bette Davis and Gary Merrill’s poetry-reading tour. She growled, “Thanks for the warning!”

How does the shy girl become the empress, metamorphosing from reticent performer to commanding presence? But Spaltro never helps us understand how Ethel’s shyness and haughtiness coexisted. Which was performance and which was genuine? Was the shyness a form of self-protection that hardened into hauteur, or did each mask serve a different purpose at different moments? There is no attempt here to synthesize Ethel’s dual nature into a coherent image of the actress and the woman.

Ethel Barrymore and Joseph Cotton in 1948’s A Portrait of Jennie.

Consider a moment early in the book when Spaltro mentions that, in 1903, John Singer Sargent saw Barrymore perform in Boston. He was so moved that he begged to sketch her. His charcoal drawing offers a glimpse of Ethel’s elusive charisma. What Spaltro’s biography needs is the literary equivalent of Sargent’s art, lines capturing what made Barrymore mesmerizing. A vignette from Margo Peters’s House of Barrymore conveys more of the actress’s mystique than Spaltro manages in her entire book: “The Corn is Green closed the following day due to the heat and the uncertainty of Ethel’s appearing that evening. [She had just learned of John’s death and broken her ankle running to answer Lionel’s phone call.] But she went on, as she always had. Stella Adler remembered getting off the train one midnight in Pennsylvania Station and seeing ahead of her a tall, straight figure in a dark coat. It was Ethel Barrymore returning from an out-of-town performance, lugging her suitcases, all alone.”

Shy Empress of the Footlights provides a reliable overview of Barrymore’s career, carefully documented and competently presented. The book fills a gap; there has been no full-scale biography before this one, and Spaltro’s research provides future scholars a foundation to build on. For readers interested in the Barrymore dynasty, this volume complements Spaltro’s earlier work on Lionel and provides useful context for understanding the siblings’ interconnected careers.

But the First Lady of the American Theater deserves a biography that understands what theatre is, that it not just a series of openings and closings, successes and failures, but a living art that makes psychological demands, that calls for an artist’s imagination to take risks. Barrymore’s lost theatrical world deserves to be recreated, not just documented. Spaltro has given us Ethel’s itinerary. We’re still waiting for a biographer to take us on the journey.

Tom Connolly is Professor Emeritus of Humanities and Social Sciences at Prince Mohammad Bin Fahd University. He recently edited a historical study (in English) of the 19th- and 20th-century Jewish community of Döbling for the Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Institut für Kulturwissenschaften. His book Goodbye, Good Ol’ USA: What America Lost in World War II: The Movies, The Home Front and Postwar Culture is forthcoming from Houghton Mifflin/PMU Press.

Tagged: "Ethel Barrymore: Shy Empress of the Footlight", Ethel Barrymore