Book Review: “Sixties Surreal” — A Jingle-Jangle of an Alternative Take

By Trevor Fairbrother

While I heartily recommend Sixties Surreal as a provocative revisionist compendium or almanac, I know the volume will frustrate those who expect to find a conventional survey.

Sixties Surreal (Yale University Press, 403 pages, $50) is the hefty and engrossing catalogue for an exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art that featured over 150 works in various media, including painting, sculpture, assemblage, collage, photography, and film. It was edited by the team in charge of the show: Dan Nadel, Laura Phipps, Scott Rothkopf, and Elisabeth Sussman. The book can be glimpsed in a rapid-fire video posted by Yale University Press.

In the “Foreword,” the Whitney’s director (Rothkopf) takes credit for the “germ of an idea” that sparked the show. Back in 1999, as a Harvard undergraduate, he wrote a thesis titled “The Other Sixties: The Return of Surrealism in American Art and Culture.” Rothkopf took his cues from an agitational exhibition that Gene Swenson curated in Philadelphia in 1966: The Other Tradition. Swenson insisted that the proponents of American formalist abstraction were prejudiced against the alternative current embodied in Dada, Surrealism, and Pop Art. In hindsight, Rothkopf regrets that his youthful remapping of the ’60s focused “almost exclusively on white artists and critics living in New York.” No surprise, then, that he wanted Sixties Surreal to encompass creative networks in San Francisco, Los Angeles, Chicago, Houston, and Austin, and to feature a racially diverse group of more than 100 artists, half of them women.

The director’s statement is followed by a somewhat woolly introductory essay authored by Nadel, Phipps, and Sussman. They position the project as a radical new reassessment of the decade. This is their description of the lay of the land: “The specific qualities of societal distrust that rendered the 1960s destabilizing pushed artists to imagine new futures: surrealism gave explosive, kaleidoscopic dimensions to those imaginings.” Vowing not to rehash history and redouble categorizations, the curators set out to help artists who were overlooked and undervalued in recent decades. They fashion a counter-canon aimed at the deficiencies of art historical orthodoxies that purportedly took hold in the early ’70s: the notion of “a single formalist mainstream centered in New York” and the “proscribed definition of ‘Art’ that privileged formal considerations over content.”

Things become confusing because they attach the word “surreal” to two different trends. The first concerns the abiding interest in Surrealism, the literary and artistic movement that flourished in Paris in the ’20s in response to André Breton’s first “Surrealist Manifesto.” The second refers to “the surreal,” by which they meant the “broader and more generic dissemination” of Surrealism. They dub this a “popular cousin” of Surrealism, and describe it as an archetypically ’60s savoring of anything weird or dreamlike or off-kilter.

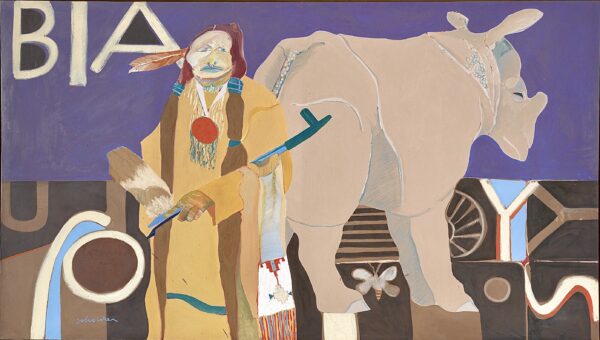

Fritz Scholder, Indian and Rhinoceros. 1968; Oil paint on canvas. Collection of the National Museum of the American Indian; © Estate of Fritz Scholder

Over 360 pages of this book are devoted to an evenly paced mixture of 11 essays and 15 timelines for the years 1958 to 1972. The essays are relatively short and range in approach from engagingly insightful to pedantic; some focus on one person or a particular exhibition, while others offer broader takes on art made by Blacks, Chicanos, feminists, queers, and West Coast assemblagists. The idea for a 15-part chronology emerged when the research team was gathering biographical information about all the artists in the exhibition. Their next goal was to map the connections those people experienced, either as art students or contributors to such key thematic exhibitions as Hairy Who (Chicago, 1966), 66 Signs of Neon (Watts, California, 1966), Eccentric Abstraction (1966, New York City), and Funk (Berkeley, California, 1967). Together, the timelines chart a unique historical narrative keyed to the lives and experiences of the artists chosen for the exhibition. The information they contain is amplified in a remarkable group of comparative illustrations – images of artists, art galleries, posters, and period publications.

I did not visit the exhibition, but enjoyed the short, amiable video – Stroll through Sixties Surreal – that the Whitney made for its website. In addition, I need to note that I could not judge the merits of catalogue without taking account of the considerable press coverage that the show attracted. Things got off to a lively start with the preview published in the New York Times two weeks ahead of the opening. The writer, Deborah Solomon, hailed the project as a “thrillingly revisionist history” and anticipated a “socially relevant and ethically concerned exhibition.” The title of Solomon’s article – “Roll Over Warhol: Taking The ’60s Beyond Pop Art” – referenced Chuck Berry’s “Roll Over Beethoven.” It was a clever way to say that Sixties Surreal intends to move beyond the ideologies about Pop Art and Minimalism established decades ago. Solomon spiced her article with quotes from conversations with several insiders, including Rothkopf, who confessed to making last-minute adjustments to the show. After the catalogue had gone to press, he added one work by Andy Warhol and one by Jasper Johns. Clearly, these “recognizable figures” were supposed to boost the show’s blockbuster potential.

Two works from Nancy Graves’ 1968-69 Camel series (National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa) installed at the entrance of Sixties Surreal in 2025.

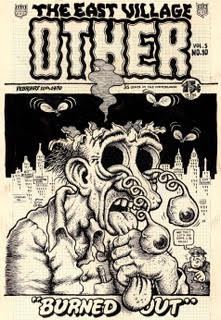

Critical responses to the Whitney’s exhibition were lively and mixed. It was generally greeted as a significant achievement; readers were assured that they would find a sufficiency of amazing and challenging works. The list of treats included: Harold Stevenson’s gargantuan male nude painting (The New Adam, 1962); Martha Edelheit’s self-portrait in the act of painting a panorama of naked women (Flesh Wall With Table, 1965); Fritz Scholder’s tragicomic take on the relationship between Indigenous nations and the antiquated, untrustworthy Bureau of Indian Affairs (Indian and Rhinoceros, 1968); Nancy Graves’s three realistic, life-size animal sculptures (Camel VI, Camel VII and Camel VIII, 1968-1969); and Robert Crumb’s repulsive homage to the urban walking wounded (Burned Out, a 1970 cover design for The East Village Other).

The exhibition had a singular capacity to get under the skin of those tasked with reviewing it, as these comments suggest:

- “The show is organized around five intersecting themes: the mutation and Americanization of Surrealism; the psychosexual as both liberation and trauma; the fantastical as escape and confrontation; revolutionary politics in all their tragic intensity; and a spirituality or mysticism unbound by doctrine. What [the curators] have foregone is any attempt to link them together.” (Saul Ostrow, Tussle)

- “[The] grey-on-grey Andy Warhol Marilyn from 1967 … feels about as surreal as a pancake.” (Ben Davis, Artnet)

- “The net has been cast so wide that nothing much gets caught. Ask yourself, what Sixties artwork couldn’t be shown here? What wasn’t surreal, somehow?” (Jackson Arn, Art in America)

- “By the end of the exhibition, I felt like I’d lost the plot on what ‘surrealism’ even means – a pretty surreal experience of the unintentional kind.” (Lisa Yin Zhang, Hyperallergic)

- “The connection to anything surreal is absent from most of the art here. … While the view of surrealism may be hazy at the Whitney, the lasting impact of the ’60s has never been clearer.” (Brian P. Kelly, Wall Street Journal)

- “It’s a big mess of a show, full of both first-rate and third-rate work, strung together with little cohesion or argument.” (Philip Kennicott, Washington Post)

Robert Crumb, Burned Out, 1970. (Lucas Museum of Narrative Art, Los Angeles)

The decision to install the works of art according to thematic groupings probably backfired with some visitors, as it did with several critics. The curators arrived at several straightforward topics: art protesting war and racism; collages and assemblage sculptures; and art made by women. Other subjects were less obvious: art exploring spirituality and ancestral culture; art inspired by the body’s sensual feelings; art presenting the strangeness of modern life, especially the onslaught of televised information; and art offering a look “underneath the slick surfaces of consumer culture and Pop Art.” Imposing a subject-based reading on any work of art requires considerable curatorial ingenuity and finesse, especially when the work was made by an artist who eschewed categorization. In her preview, Deborah Solomon included this comment by 94-year-old Martha Edelheit, whose work had not previously been exhibited at the Whitney: ” I don’t know why I was asked to be in it. The title of the show bewildered me because I don’t think of anything I do as Surreal.”

As one would expect, the catalogue for Sixties Surreal proves more helpful with regard to subject matter. While I heartily recommend the publication as a compendium or almanac, I know that it will frustrate those who expect to find a conventional survey. It serves the lesser-known artists very well, but assumes that established figures need little or no introduction. Sol LeWitt, whose name is synonymous with Minimalism and Conceptual Art, is a case in point. His work was absent from the exhibition and not illustrated in the catalogue, but his name, unsurprisingly, appears in the index. Alas, the text does not discuss his art and career. In this project’s interpretive framing, he is singled out for his stalwart and generous friendships with the artists Eva Hesse and Lee Lozano (both included in the show and catalogue) and the curator Lucy Lippard (whose exhibition Eccentric Abstraction was the subject of a catalogue essay). I know from personal experiences of working with LeWitt that he was a generous and thoughtful individual. He surely would not mind that Sixties Surreal salutes his humanity rather than his art.

Trevor Fairbrother wrote about Salvador Dalí for The Arts Fuse in 2024. As curator of contemporary art at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, in the 1990s he guided the acquisition a large sculpture by Sol LeWitt and two examples of his wall drawing practice.

Tagged: "Surreal Sixties", Dan Nadel, Elisabeth Sussman, Laura Phipps, Scott Rothkopf, Sixties art