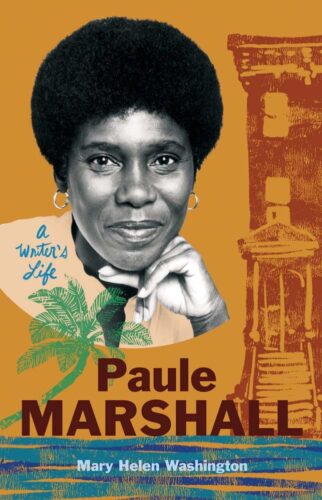

Book Review: A Writer’s Life Reconsidered — Paule Marshall’s Artistry and Influence

By Bill Littlefield

Mary Helen Washington’s biography of Paule Marshall provides a thorough consideration of the writer’s achievement and a convincing case that her fiction and her public speeches deserve continuing attention and respect.

Paule Marshall: A Writer’s Life by Mary Helen Washington. Yale University Press (Black Lives Series), 297 pages, $30.

One indication of the success of Mary Helen Washington’s biography of Paule Marshall is that, having enjoyed the book, I look forward to reading a couple of the Black writer’s novels. The volume presents inviting summary discussions of Marshall’s fiction, so I probably won’t be the only reader inclined to read on. Washington, a professor emerita in the English department at the University of Maryland, also provides a thorough consideration of Marshall’s achievement and a convincing case that her novels and her public speeches deserve continuing attention and respect.

Paule Marshall grew up in Brooklyn, but her heritage was West Indian, and Washington immediately turns to one of the benefits of that background: the music of the island’s language. Marshall’s mother, whom Marshall credits with inspiring her love of words, threatens her daughters with the “dire consequences that awaited us should we become ‘little ring-tail concubines caterwauling about the streets looking for men,’” or come home “‘tumbling big with some wild-dog puppy.’”

In Brown Girl, Brownstones, The Chosen Place, the Timeless People and other novels, Washington contends that Marshall created “fictional women who push the boundaries of social and sexual restraints.” She also credits the woman’s fiction, along with her public presentations at conferences and elsewhere, with dramatizing her “interest in the black global world, the histories and powers of indigenous cultures, the relationship between racial violence, capitalism, and colonialism, and a concern for ‘the wretched of the earth.’” “In all of Paule’s fiction,” Washington contends, “the black middle class is charged with the moral and political choice of aligning themselves with colonial or racist systems or remaining close to the people ‘at the bottom of the heap.’”

Marshall’s writing was also therapeutic. Washington points to a particular literary conference at Dartmouth during which an African-American student hurt the author’s feelings by questioning Marshall’s identification as “Black,” given that her background was West Indian. Exploring issues of identity was an ongoing concern for Marshall throughout her fiction. As the biographer puts it, “in her fictional world, she examined, explored, and/or gave us a heightened awareness of the veils of secrecy and dissemblance experienced by the Black women she imagined.” This perspective did not result in stereotypical stories about the inevitability of empowerment. In her final novel, The Fisher King, its protagonist, Hattie, is left “bereft and apparently powerless.” Marshall was “understandably exasperated with readers who were perplexed about the ‘unhappy’ ending.” Washington quotes Marshall as saying, “Well, the book is not about happiness, for god’s sake. It’s about the way we are as humans.”

Washington adds: “Perhaps she meant it’s the way we are as women artists.”

Marshall traveled widely, sometimes as a cultural ambassador for the U.S. She was twice married and had a son, but ultimately found marriage incompatible with “the writer’s life.” In Washington’s estimation, Marshall did not receive the literary recognition she deserved, either from the reading public, critics, or the literary establishment. Other Black writers who were her contemporaries — perhaps most notably James Baldwin and Ralph Ellison — were more celebrated.

Still, Marshall was hardly neglected. Over the course of her life, she received a Guggenheim Fellowship, a National Medal of Arts Award, the John Dos Passos Prize for Literature, and a MacArthur Fellowship. After her death in 2019, Marshall was remembered in a New Yorker piece (by Edwidge Danticat) along with Toni Morrison, who had died seven days before Marshall did. Washington’s conclusion is that, with this pairing, Marshall finally “was granted the stature she so richly deserved.”

Bill Littlefield’s most recent books are Mercy (Black Rose Writing) and Who Taught That Mouse To Write? (Writing Mouse Press).