Book Review: Moments of Cinematic Illumination in Akira Kurosawa’s Uneven “Long Take”

By Gerald Peary

Long Take is a somewhat dry read; there are some great passages, but too many rambling, unfocused sections for it to be a satisfactory sequel to the Japanese director’s 1983 memoir.

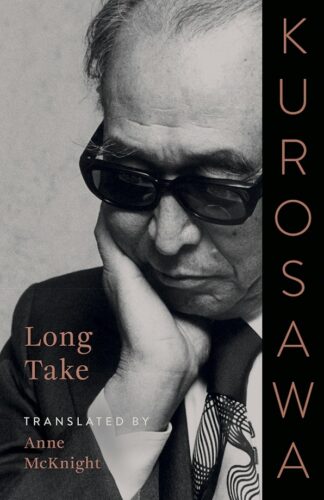

Long Take by Akira Kurosawa. Translated by Anne McKnight. University of Minnesota Press, 240 pages, $12.95 (paperback).

Akira Kurosawa’s Something Like an Autobiography (1983) ended abruptly, with the filmmaker’s sudden leap to international fame in 1950 after making Rashomon. Long Take, published in Japan in 1998 after Kurosawa’s death, seeks to fill in his later days with a combination of interviews, reminiscences, and remembrances. Though capably translated into English by Anne McKnight, Long Take is a somewhat dry read with great passages but too many rambling, unfocused sections to serve as a satisfactory sequel to the director’s actual memoir.

Akira Kurosawa’s Something Like an Autobiography (1983) ended abruptly, with the filmmaker’s sudden leap to international fame in 1950 after making Rashomon. Long Take, published in Japan in 1998 after Kurosawa’s death, seeks to fill in his later days with a combination of interviews, reminiscences, and remembrances. Though capably translated into English by Anne McKnight, Long Take is a somewhat dry read with great passages but too many rambling, unfocused sections to serve as a satisfactory sequel to the director’s actual memoir.

The overall impression is that Kurosawa, who died at 88, led a prosperous, satisfying life, with few hazards in a career of thirty feature films, including such world classics as Ikiru, The Seven Samurai, Ran, Yojimbo, and High and Low. Outside of Japan, he was revered, whether drawing crowds of adulating young cineastes in France or being treated almost like a deity by Spielberg, Lucas, and Coppola when he visited LA. He was pals with Satyajit Ray, Andrei Tarkovsky, Sidney Lumet, and he and his wife rode elephants together with Michelangelo Antonioni and Antonioni’s wife.

And at home? His daughter Kazuko noted, “Because my mother never made my father do anything, and took care of all his needs herself, my father never knew anything but movies.”

Kurosawa’s biggest complaints in Long Take are aimed locally: at the Japanese citizenry for having little interest in their own cinema, and at provincial filmmakers for rarely leaving home, for philistine film producers who cared only about profits instead of good cinema. (When I attended the First Tokyo Film Festival in 1985, Kurosawa imperiously banned all Japanese journalists from a press conference for his new movie, Ran.) In an interview in Long Take, he admitted rarely venturing into downtown Tokyo, irritated by young people who dyed their hair green and whose gender was indeterminate.

So whom does Kurosawa like? An earlier generation of Japanese filmmakers for sure—the three giants, Ozu, Mizoguchi, Naruse—but, in his favor, there are occasional picks of movies of younger Japanese directors like Oshima, Yamada, and Kitano. Above all, America’s John Ford, who, like him, was a self-educated, hard-drinking “man’s man.” He met Ford on a variety of occasions and was in awe. “…[W]hen I appeared… in front of John Ford, I was really formal and on my best behavior, way back then.”

John Ford and Akira Kurosawa meeting during the filming of Gideon’s Day (1958).

He readily admits the deep influence of Ford’s westerns on his own samurai works. There’s an interesting chapter in Long Take in which Kurosawa speaks of his excitement about the first Ford biography published in Japan, Pappy, by Dan Ford, John Ford’s grandson. Kurosawa: “Reading this book really calls up a lot of scenes; I can almost see John Ford appear before my eyes.” It’s clear how much Kurosawa idealizes his favorite director, turning Ford’s infamous belittling of his actors into a virtue (“his grouchiness was all a shtick”), and wrongly declaring that Ford was a liberal in his last days. In truth, Ford in old age embraced Richard Nixon and heartily supported the Vietnam War.

Kurosawa: “John Ford died while I was making Dersu Uzala, but my staff kept the news from me until I was through shooting.”

Long Take is short on revelatory stories about Toshiro Mifune, Kurosawa’s great star, and there’s nothing at all about many of his most noteworthy films. Zero on Ikiru, for instance, or its sublime lead actor Takashi Shimura. But there’s quite a lot about the making of The Seven Samurai. According to its filmmaker, the screenplay is an amalgam of many sources, including War and Peace, an obscure Russian proletariat novel, and Japanese folk tales. It began with the idea of tracing the life of a single samurai — Kurosawa: “Did he really wash his face in the morning? Did he brush his teeth?”– and then expanded arbitrarily to seven. “I just went with a gut feeling, and we felt we needed seven, minimum. To protect the village, that kind of thing.”

Thankfully, there is one chapter of Long Take which is a treasure, “Kurosawa’s 100 Films,” a list compiled by his daughter of his all-time favorites from world cinema, with each title followed by a telling paragraph of praise from the filmmaker. The list is as wonderfully eclectic as one could possibly desire. There are expected masterpieces like Chaplin’s The Gold Rush, Renoir’s Grand Illusion, De Sica’s The Bicycle Thieves, and, from Japan, Ozu’s Late Spring, Mizoguchi’s Life of Oharu, Naruse’s Floating Clouds. But there are also delightful Hollywood popular films like The Thin Man, Ninotchka, Daddy Longlegs, Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?, and It’s a Wonderful Life (an influence on Ikiru?). And, incredibly, Godzilla!

And an anime, My Neighbor Totoro. And a 1956 western I’ve never even heard of, The Proud Ones, directed by someone named Robert E. Webb. Kurosawa: “That was a wonderful movie. Webb used Robert Ryan so well in his role, and the camerawork is amazing. As always, Lucian Ballard is just a model cinematographer.”

Kazuko Kurosawa: “My father would be overjoyed if readers of this list ended up even seeing one new film, as he loved movies with all his heart.” Will anyone join me for a viewing of The Proud Ones?

Gerald Peary is a professor emeritus at Suffolk University, Boston; ex-curator of the Boston University Cinematheque. A critic for the late Boston Phoenix, he is the author of nine books on cinema; writer-director of the documentaries For the Love of Movies: The Story of American Film Criticism and Archie’s Betty; and a featured actor in the 2013 independent narrative Computer Chess. His last documentary, The Rabbi Goes West, co-directed by Amy Geller, played at film festivals around the world, and is available for free on YouTube. His 2024 book Mavericks: Interviews with the World’s Iconoclast Filmmakers, was published by the University Press of Kentucky. His newest book, A Reluctant Film Critic, a combined memoir and career interview, can be purchased here. With Geller, he is the co-creator and co-host of a seven-episode podcast, The Rabbis Go South, available wherever you listen to podcasts.