Book Review: Blonde Ambition in Postwar Britain: Lynda Nead’s “British Blonde” and the Performance of Desire

By Peter Walsh

Lynda Nead’s meticulous, competent, and impressively researched approach gives the work weight without making it ponderous; British Blonde seems destined to serve as a text for classes in gender or cultural studies.

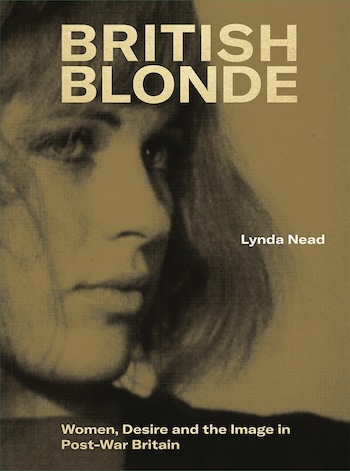

British Blonde: Women, Desire and the Image in Post-War Britain by Lynda Nead. Yale University Press, 240 pages, $40

Is it true blondes have more fun? Maybe not in Britain. The platinum protagonists of Lynda Nead’s British Blonde: Women, Desire and the Image in Post-War Britain include two notorious murderers (one hanged, the other sentenced to decades in prison); an artist who died tragically young, actresses trapped in endless “dim blonde” roles in smutty comedies; and tough products of working class backgrounds who aspired to rise but never quite made it past their accents and bustlines. All of these real women were famous or infamous in their day, though not necessarily on this side of the Atlantic.

Is it true blondes have more fun? Maybe not in Britain. The platinum protagonists of Lynda Nead’s British Blonde: Women, Desire and the Image in Post-War Britain include two notorious murderers (one hanged, the other sentenced to decades in prison); an artist who died tragically young, actresses trapped in endless “dim blonde” roles in smutty comedies; and tough products of working class backgrounds who aspired to rise but never quite made it past their accents and bustlines. All of these real women were famous or infamous in their day, though not necessarily on this side of the Atlantic.

Nead’s diction and vocabulary are academic, but her contexts and scenery are right out of a noir film or a soft-core porno magazine: she takes her readers to the smoke-fogged interiors of West End bars and nightclubs; to the amateur camera clubs where men could, for a fee, photograph nude female models (perhaps even without film in their cameras); to a lonely Yorkshire moor (site of horrific child murders); and to a cramped, almost theatrical courtroom at the Old Bailey. Several of Nead’s blondes enjoy considerable financial and professional success, but, in her book, the category of “British Blonde” comes off as a bit artificial and secondhand, a little downmarket and out of focus, never really respectable if occasionally glamorous, defined by some more authentic, more famous, foreign celebrity. Actress Diana Dors is “the British Marilyn.” Pop artist Pauline Boty is the “Wimbledon Bardot.” Carol White, “a working class version of the more established cinema blondes,” is the “Battersea Bardot,” tagged by one critic as “an actress who looks like Julie Christie and sounds like Clapham Common.”

Nead is an art historian and her study is a serious one, published by Yale’s Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art. Its genre, which may seem fuzzy, is partly elucidated by its subtitle — a well-illustrated, scholarly mixture of art, social history, sociology, sexual politics, political commentary, feminism, visual studies, and cultural criticism, with an emphasis on the last. The book’s structure is both chronological and biographical. Moving along through the 1950s and ’60s, Nead chooses a different blonde, emblematic of British popular culture of particular moment, for each chapter: The British Marilyn, Blond Noir, Carry On Blonde, Sixties Blonde. The book’s chronology ends around 1973, well before the most famous British Blonde of all, Diana, Princess of Wales, appeared on the scene.

Nead doesn’t dwell on it, but it is hard not to think of the contrast between the British blonde and the American variety that the Brits looked at with more than a little envy. As in the still famous Clairol ads, “fun” is the operative word in American blondedom. American blondes are said to love an (ostensibly) innocent good time: fun on the beach or poolside, gliding down the highways in a stylish convertible, dressed, like Barbie, in the latest, form-fitting fashions, hanging out with a handsome boyfriend, enjoying the best of the American dream. American blondes do not aspire because usually they are already there. Their status as a sex symbol is a birthright.

In contrast, Nead’s British blondes struggle with inconvenient, regional accents (like many women of the period, several in the book take elocution lessons) and a suffocating, inflexible British class system. Peroxide blonde Ruth Ellis, described during her trial as a “model” and “nightclub hostess” and as a “typical West End tart,” murders her posh, abusive, race-car-loving paramour, born well above her station. She is famously hanged for the crime at the age of 28, the last woman to be hanged in Britain. Nead shows how Ellis took on the mutually impossible tasks of rising to fashionable respectability while simultaneously cultivating unabashed sexiness. This included the blonde hair that she felt she needed to attract the sort of man who could finally free her from her working class origins. Nead describes, with sympathy, her path: “In her teens and twenties, Ellis sought to better herself; she chose from the limited routes available to her and she transformed her appearance to become the glamorous woman in the dock at the Old Bailey in 1955. Ellis sought to ‘pass’ as a professional, middle-class Englishwoman and to mix in social classes higher than her own; blonde for Ellis was a sign of glamour and sophistication.”

Actress Diana Dors, the British Marilyn Monroe, in the ’50s. WikiMedia

Ellis’s sensationalized trial and pending execution inspired protests. “While British audiences were held captive by Ellis’s story…,” Nead writes, “there was also a powerful outcry against the barbarity of the sentence and the insensitivity of the British legal system.”

Most of Nead’s case studies achieved fame as actresses, underlining her conception of the blonde as a figure on a public stage. They typically trade on their blond hair, attractive features, erotic physiques, and comically large (in Nead’s analysis) breasts. Curvaceous and talented Diana Dors, the British Marilyn, Nead implies, was betrayed by her own glamorous image and enormous boobs. “Dors was a contradictory figure for post-war Britain,” Nead says, “at once, all body and a cartoonish parody; stimulating and vulgar; a national icon and a transgression of British values.”

Barbara Windsor, the Carry On blonde, was best known for being cast in the formulaic “Carry On” comedy franchise (Carry on Doctor, Carry On… Up the Khyber, Carry on Cleo, Carry on Sergeant, Carry on Screaming, etc.) — genre films which, like the satirical Monty Python series, drew on the raucous Victorian music-hall tradition for inspiration. Nead writes that “Carry On films are low comedy, a tradition that goes back to classical Greece and is based on physical humor and bodily desire.”

Carry On‘s blonde in residence, Barbara Windsor. Photo: WikiMedia

Nead sees Windsor as caught between two decades, not quite fitting into either of them. “Barbara Windsor’s ‘glamour’ is not that of a 1950s sex goddess,” Nead writes, “but a cheap and vernacular representation of desire and sexuality in 1960s Britain. She sits on the borderline of being in control of her image and of being manipulated by the people and social forms around her.”

Artist Pauline Boty, the sixties blonde, comes closest to escaping the British blonde stereotypes, though perhaps, Nead suggests, only to fall into another set of stereotypes in liberated “Swinging London.” Born into a conservative, middle class family (her father was a domineering accountant who tried to thwart her artistic education), she studied at the Wimbledon School of Art. She became an important figure in the British Pop Art movement — its only acknowledged female founding member. As a painter, she frequently played with the themes Nead examines in her study: “Boty’s engagement with the performance of blonde is a play on identity and what it is to be a woman and an artist in Sixties Britain; in part critique and in part collusion…” Young and movie-star attractive (she acquired the “Wimbledon Bardot” nickname in art school), Boty frequently used her image and body as material for her art. “Boty references contemporary motifs and themes such as the single girl, the pin-up, desire, class, sex, obscenity, whiteness, and modernity. She exposes blondness as the ultimate masquerade and makes explicit its social and cultural construction.”

The “Wimbledon Bardot,” Pauline Boty. Photo: WikiMedia

Boty’s role as a cultural figure of the sixties was established by her appearance in Ken Russell’s film Pop Goes the Easel, broadcast by the BBC in March 1962. Following that appearance she was offered acting roles in television and theater and appeared in magazine spreads and on BBC radio cultural programs. She worked as an actor, model, and artist for the rest of her short life. She died tragically of cancer in July 1966 at the age of 28.

British Blonde is copiously and appropriately illustrated with period advertisements, magazine covers, tabloid pages, cartoons, comic postcards, movie posters and stills, fashion spreads, paintings, and photographs. Nead’s meticulous, competent, and impressively researched approach gives the work weight without making it ponderous; it seems destined to serve as a text for classes in gender or cultural studies. Her clean prose style, deadpan ironies, arresting cast of characters, and remarkably detailed and exhaustive analysis could have an appeal well beyond an academic audience.

Peter Walsh has worked as a staff member or consultant to such museums as the Harvard Art Museums, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Davis Museum at Wellesley College, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art, and the Boston Athenaeum. He has published in American and European newspapers, journals, and in scholarly anthologies and has lectured at MIT, in New York, Milan, London, Los Angeles, and many other venues. In recent years, he began a career as an actor and has since worked on more than 100 projects, including theater, national television, and award-winning films. He is completing a novel set in the 1960s.

Nice summary of this book. I’ve always been fascinated by the travesty of Ruth Ellis. I believe I once read that she was “the calmest person to ever walk the gallows.” Having just watched Man Bait from 1952 (aka The Last Page) with Diana Dors, your review had my attention. It’s good to know it is not just for academic reading – sounds like a lively read.