Book Review: “The Musical Lives of Charles Manson” — Scenes from a Counterculture

By Trevor Fairbrother

Nicholas Tochka is less interested in crafting a coherent portrayal of Charles Manson’s “musical lives” than in connecting his critical hypothesis of “the invention of the Sixties” to critical theories.

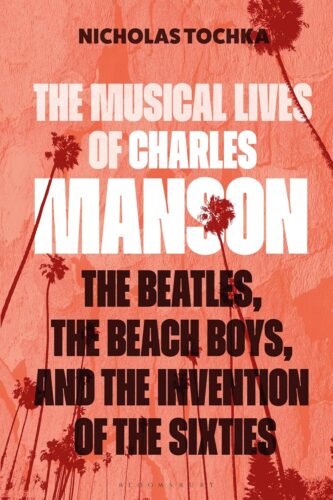

The Musical Lives of Charles Manson: The Beatles, the Beach Boys, and the Invention of the Sixties —or, No Sense Makes Sense by Nicholas Tochka. Bloomsbury, 288 pages, $22.45 (paperback)

When Nicholas Tochka began work on a project about Charles Manson, he envisioned an “experimental biography [that] explores the intersections between rock criticism, postwar narrative forms, and the historiography of ‘the 1960s’ in the US imagination.” The finished book has a title so long that it is abbreviated on the cover: The Musical Lives of Charles Manson: The Beatles, the Beach Boys, and the Invention of the Sixties —or, No Sense Makes Sense. The last four words repeat one of the mind-fuck maxims that Manson wielded as a cult leader. The blurb on the back cover announces “a new take on the story of the [Manson Family] commune – and on rock’s role in fracturing the possibility of writing trustworthy histories after the Sixties.”

When Nicholas Tochka began work on a project about Charles Manson, he envisioned an “experimental biography [that] explores the intersections between rock criticism, postwar narrative forms, and the historiography of ‘the 1960s’ in the US imagination.” The finished book has a title so long that it is abbreviated on the cover: The Musical Lives of Charles Manson: The Beatles, the Beach Boys, and the Invention of the Sixties —or, No Sense Makes Sense. The last four words repeat one of the mind-fuck maxims that Manson wielded as a cult leader. The blurb on the back cover announces “a new take on the story of the [Manson Family] commune – and on rock’s role in fracturing the possibility of writing trustworthy histories after the Sixties.”

Tochka is an ethnomusicologist who teaches at Melbourne’s Conservatorium of Music. He declares his poststructuralist and paraethnographic approaches and acknowledges “the post-truth world we live in today.” In the Prologue, he urges readers not to “take too literally what is written in this book.” Even though the text is scrupulously divided into six chronological sections, from March 1967 to February 1972, it feels more kaleidoscopic than linear. It sets out a mix of facts and fictions carefully sampled from the vast literature on Manson: true crime reports; gonzo histories; memoirs by folks on the scene; and revisionist responses to all of the above. Tochka writes in an accessible scholarly style and he’s good about citing sources.

Manson was born in Cincinnati to an unmarried sixteen-year-old in 1934. He never met his father. He rebelled against his hard-drinking mother and became a juvenile delinquent and grifter. He married twice, in 1955 and 1959. In June 1960 he began a jail sentence for theft, forgery, and pimping. In prison he learned to play guitar and started to write songs. In 1964 he developed an obsession with the “Beatlemania” engulfing the US. After his parole in March 1967, he went directly to San Francisco, where he dropped his first LSD tab under the colored lights of a Grateful Dead show.

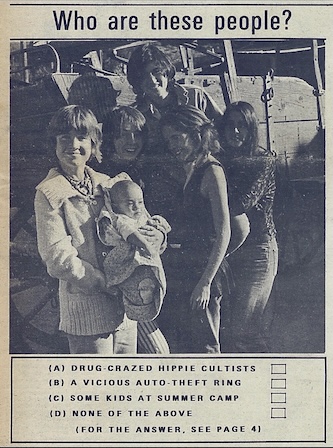

Detail of the front page of Los Angeles Free Press, February 6, 1970.

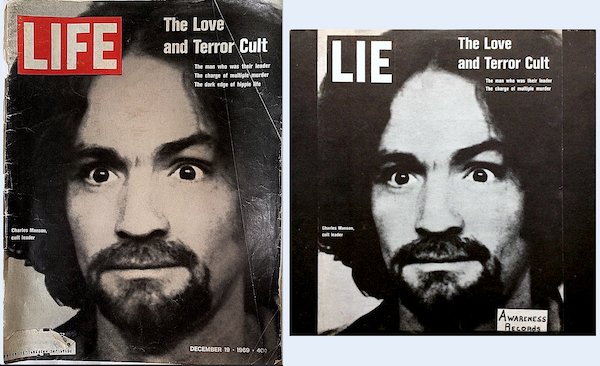

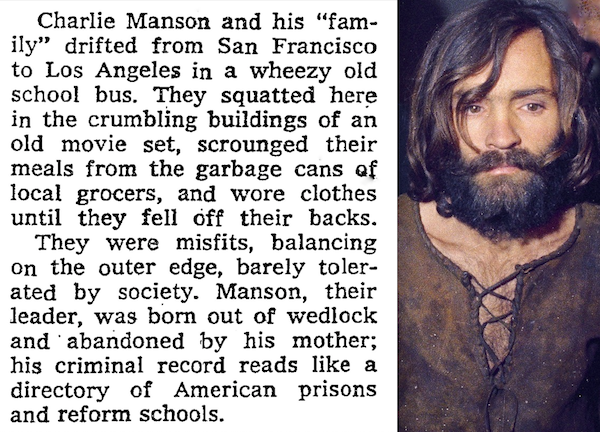

In Haight-Ashbury Manson focused on panhandling and seducing young women he encountered while playing guitar on the street and spieling about love and overcoming inhibitions. He lured vulnerable kids into joining his Family – the flock he guided with music, drugs, and group sex. But the greater American public knew none of this until December 5, 1969, when a grand jury in Los Angeles was asked to indict him for the murder of actress Sharon Tate and others. On December 19, LIFE Magazine published an exposé casting Manson as the embodiment of “the dark edge of hippie life.” The Rasputin-like photograph on the cover was a mugshot taken over a year before, when he and his followers were arrested after crashing their home on wheels – a vintage school bus – in southern Ventura County.

None of the eight illustrations in Tochka’s book shows Manson. The most compelling image is a group photograph first published on the front page of the Los Angeles Free Press in February 1970. The paper ran the snapshot as a quiz, asking readers to decide whether the smiling young women were drug-crazed hippies or car thieves or kids at summer camp or “none of the above.” In fact, they were Manson followers still living in the Family’s lodgings at Spahn Movie Ranch, in the Simi Hills. The paper published an interview with them in which they characterized Manson as a victim of “Big Brother” and “the Machine.”

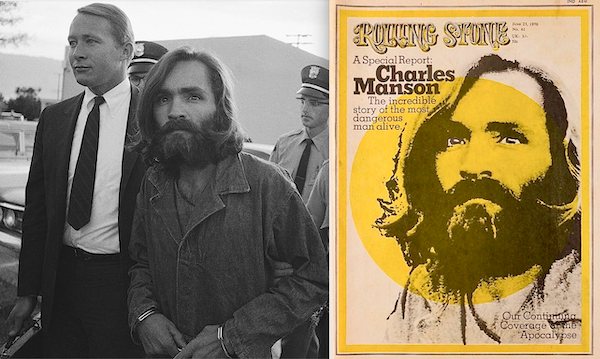

On June 25, 1970, Rolling Stone published a long feature on Manson. Long-haired and bearded, he was picture-perfect for the cover of the pioneering rock magazine founded in 1967. But the captions accompanying his photograph on the cover tagged him as a villain: “The incredible story of the most dangerous man alive” and “Our Continuing Coverage of the Apocalypse.”

During the Tate-LaBianca murder trial the press wrote little about Manson’s activities as an aspiring musician and songwriter, probably because he had no professional stature. In 1967, using an introduction from Phil Kaufman, a former prison mate in Los Angeles, he pitched his songs to Phil Stromberg at Universal Studios. A recording session followed but Stromberg failed to garner any interest. In 1968, two women from Manson’s entourage met Dennis Wilson of the Beach Boys when they were hitchhiking. Soon thereafter Manson and his followers were spending a lot of time at Wilson’s house, partying with the likes of Neil Young. Wilson had his friend Gregg Jakobson do a studio recording of Manson singing. The Beach Boys recorded one of Manson’s songs and released it as a B-side in December 1968. The relationship soured, however, because Dennis Wilson had tweaked the lyrics, changed the title from “Cease to Exist” to “Never Learn Not to Love” and took the songwriting credit for himself. In 1969, Terry Melcher, Doris Day’s only child, auditioned Manson performing, but he too chose not to make a formal offer. (A singer during the surf music craze, Melcher had produced the Byrds’ first two albums for Columbia, and was a director of the 1967 Monterey International Pop Festival.)

Left: cover of LIFE Magazine, December 19, 1969. Right: Manson’s album LIE: The Love and Terror Cult, released on Awareness Records, March 1970.

Manson’s only personal record release happened while he awaited trial. He persuaded Phil Kaufman to make a vinyl LP, which was released on March 6, 1970. Titled LIE: The Love and Terror Cult, it featured 13 songs from the demo sessions. It was a move to convince people that he was not guilty. The design of the album sleeve parodied LIFE Magazine‘s Manson cover. Kaufman made 2,000 copies and the local bootlegging company he hired sold only 300. To recoup his investment, he signed an agreement with ESP-Disk to distribute the album nationally.

Given that Tochka’s book is promoted as the “first comprehensive examination of the Manson Family’s music,” I expected to read about the origins, influences, and characteristics of his songwriting. This was not the case, nor could I tell if the author rated Manson’s songs highly or not, except for a couple of favorable asides. My background research led to an early article that Tochka does not mention. On October 4, 1970, the New York Times published Carman Moore’s review of Manson’s album LIE (the ESP release). Moore rated Manson a middling talent and “a competent sometimes interesting worker.” He said the guitar playing “leans heavily on the quasi-calypso slap and strum style popular among current folk singers.” He called Manson’s voice a “not unpleasant but hardly spellbinding low tenor.” While he found the lyrics to be “of uneven quality,” Moore thought Manson’s “putting down of modern society” was “quite fresh.” In particular he liked the “almost stream-of-consciousness” observations and the “other-worldly, Zen-like” abstractions that seemed to advocate resignation.

Left: detail of Wally Fong’s photograph of Manson being led to court, December 3, 1969. Right: cover of Rolling Stone, June 25, 1970. Photo pairing by author.

While Manson’s music has probably not grown in stature in the intervening decades, it is now within easy reach online. Propitiously, in 1982, the California post-punk band Redd Kross recorded his song “Cease to Exist.” Numerous Manson demos were featured in Mary Harron’s 2018 movie Charlie Says and in Errol Morris’s 2025 documentary CHAOS: The Manson Murders. Several years ago Neil Young told interviewers the songs were fascinating and Manson was “quite good.” But he also noted that Reprise Records turned Manson down, adding, “He wasn’t what you call a song writer, he was like a song spewer.”

Another topic Tochka examines is Manson’s love of the Beatles. During the indictment process, the press reported that several songs on their recent album had deeply affected him. Manson claimed that Black revolutionaries were about to start a race war by targeting the white middle-class. He said that he received these prophecies when listening to several tracks on The White Album – “Helter Skelter,” “Piggies,” “Blackbird,” “Rocky Raccoon,” and “Revolution 9.” When the authors of Rolling Stone‘s 1970 feature on Manson asked the inmate why he was so sure about this he allowed that the Beatles may not have deliberately and overtly expressed the messages he intuited: “This music is bringing on the revolution, the unorganized overthrow of the Establishment. The Beatles know in the sense that the subconscious knows.” Others in Manson’s circle told the reporters that Manson’s tone had recently shifted. Sgt. Pepper (May 1967) was trippy and “made Charlie very happy.” The White Album (November 1968) was more of a downer.

Left: detail of a New York Times article, December 7 1969. Right: Manson arriving at his arraignment in 1969. Photo pairing by author

I concluded that Tochka was ultimately less interested in crafting a coherent portrayal of Manson’s “musical lives” than in connecting his critical hypothesis of “the invention of the Sixties” to critical theories. When reading his book, I found it helpful to have at hand Todd Gitlin’s The Sixties: Years of Hope, Days of Rage (1987), an excellent synthesis of narrative history and personal recollection. Gitlin situated the Tate-LaBianca killings in a precise sociocultural moment: “In those plummeting days, every stark fact was pressed into world-historical significance.” Teenage vandalism was sedition, guerilla attacks were revolution, and

Manson arrived as a new and unique villain. He was an “acidhead” with a “harem-commune.” He was “readymade as the monster lurking in the heart of every longhair, the rough beast slouching to Beverly Hills to be born for the next millennium.”

Trevor Fairbrother wrote his first essay for The Arts Fuse in 2023 (Boston and Sargent, For Better, For Worse). Vis-à-vis the Los Angeles subcultures of the ’60s, he contributed A Deep Dive into The Mothers of Invention’s ‘Plastic People’ in 2024.

Tagged: "The Musical Lives of Charles Manson", Charles Manson, Music Criticism, Nicholas Tochka, The Beach Boys, The Beatles, The Sixties

A prolific writer (and once president of SDS), the late)Todd Gitlin’s book is terrific. While journeying down the nostalgic rabbit hole of crazy, I also recommend Jeffrey Melnick’s Creepy Crawling: Charles Manson and the Many Lives of America’s Most Infamous Family, another informative history of what went on in LA during the time that Manson was colonizing young brains.

Thanks for your good feedback, Tim. I haven’t seen Melnick’s book but I checked and saw that Nicholas Tochka commended it in the first of his many endnotes. He also pointed to Jeff Guinn’s fine 2013 biography, which I appreciated because I knew little about Manson prior to writing this review.