Film Review: James L. Brooks’s “Ella McCay” — A Clumsy Misstep for a Master of Ensemble Comedy

By Tim Jackson

The film skims across topical issues aimlessly; it strives for relevance but never achieves it.

Ella McCay, written and directed by James L. Brooks. Screening AMC Cinemas, Alamo Drafthouse, and Apple Cinemas Cambridge

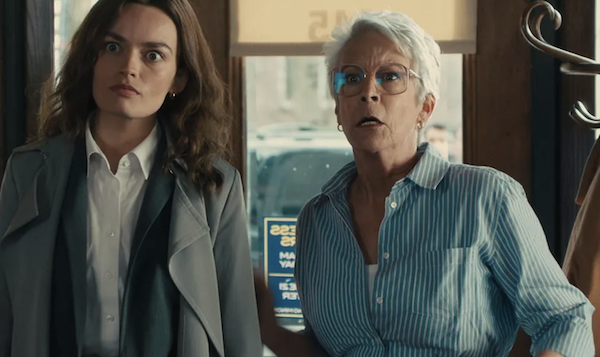

Emma Mackey and Jamie Lee Curtis in a scene from Ella McCay.

For over 40 years, James L. Brooks has assembled some of the most memorable ensembles in film: Debra Winger, Shirley MacLaine, Jack Nicholson, Danny DeVito, Jeff Daniels, and John Lithgow in Terms of Endearment (1983); Holly Hunter, William Hurt, and Albert Brooks in Broadcast News; Jack Nicholson and Helen Hunt in As Good as it Gets. Brooks helped usher Wes Anderson’s first film, Bottle Rocket, into theaters, and he was a producer for the Mary Tyler Moore Show and the Tracey Ullman Show. He was also the first to hire Matt Groening, creator of The Simpsons.

These accomplishments are worth mentioning because Brooks’s latest film, Ella McCay, which he wrote and directed, strains for the same chemistry. The film boasts a first-rate ensemble of actors, tempers its comedy with social observation, and exudes a bittersweet understanding of human fallibility. But the film feels like a throwback to the past in the least flattering sense; it is a movie in which characters serve as catalysts for comic situations rather than people with interior lives. The film skims across topical issues aimlessly; it strives for relevance but never achieves it. The result is a movie that wants to matter, but falls short.

Ella McCay, is played by Emma Mackey (of Netflix’s Sex Education series) in a plot that lurches from scene to scene. Since childhood, Ella has been estranged from her father (Woody Harrelson). His philandering ways have split the family apart, though he continues to pop back up into her life, asking forgiveness for his past. In his absence, Ella was raised by her overprotective aunt (Jamie Lee Curtis). Despite this challenging family situation, Ella rises to the position of Lieutenant Governor of an unnamed state. When the acting governor (Albert Brooks) accepts a position in the Presidential cabinet, Ella is suddenly thrust into the governorship. She is full of idealism, but her personal life remains a mess. Her husband — her former high school sweetheart (Jack Lowden) — is grasping and insecure. Her brother Casey (Spike Fern) has both emotional and personal issues. All this domestic turmoil is commented on by a narrator, Ella’s faithful secretary, Estelle (Julie Kavner).

Brooks seems to have lost control of his characters, who are unconvincing and don’t belong in the same movie. Emma Mackey is beautiful and charming, but comes off like a nervous high school valedictorian, not a woman who could rise through the ranks of state politics. Jamie Lee Curtis’s performance is a litany of smirks and gestures, screeches and admonishments. Scottish actor Lowdon, whose lengthy credits in theater, film, and series television include Benediction and the series Slow Horses, is given free rein to overact through a succession of annoying arguments. There’s no chemistry between the performers; gratuitous flashbacks do little to create belief that there was once a viable romantic connection between the two. As Ella’s repressed brother Casey, Fern (another British actor), supplies a mumbling impression of Mark Ruffalo. Both Harrelson and Brooks rehash their standard personas — they play poor imitations of themselves. Brooks’s awful white wig is so badly fitted it looked like it might come loose at any minute. The real nails-on-the-blackboard ingredient is Julie Kavner’s Marge Simpson-like narration. When she’s on camera, she overdoes every waddle and glance. I grew so tired of watching her that I started looking at the background actors. Even they seem to be overacting. To make matters worse, sloppy editing and poor continuity, compounded by ill-timed close-ups, make the film difficult to watch.

Writer-director Brooks, now 85, has let his cast gallop free when restraint was demanded. It doesn’t help that unnecessary music cues are used when the emotional tone of a scene is perfectly clear. Continuity issues abound, and the editing rhythms are jumpy. In earlier films, Brooks has successfully combined character quirks with compelling stories that embrace larger themes. But Ella McCay‘s script moves incoherently from scene to scene, without maintaining a consistent tone. The story barely feels credible; some scenes are gratuitous and/or incomplete. Working with a director with a well-earned reputation for helping to create engaging, sharp performances must have been tempting for actors who love to overplay; making Ella McCay may have been fun for the ensemble. But this ambitious attempt to satirize contemporary issues of gender and politics never gains a firm grasp of what it’s supposed to be.

Tim Jackson was an assistant professor of Digital Film and Video for 20 years. His music career in Boston began in the 1970s and includes some 20 groups, recordings, national and international tours, and contributions to film soundtracks. He studied theater and English as an undergraduate, and has also worked helter-skelter as an actor and member of SAG and AFTRA since the 1980s. He has directed three feature documentaries: Chaos and Order: Making American Theater about the American Repertory Theater; Radical Jesters, which profiles the practices of 11 interventionist artists and agit-prop performance groups; When Things Go Wrong: The Robin Lane Story. And two short films: Joan Walsh Anglund: Life in Story and Poem and The American Gurner. He is a member of the Boston Society of Film Critics. You can read more of his work on his blog.

Tagged: "Ella McCay", Albert Brooks, Emma Mackey, James L. Brooks, Jamie Lee Curtis, ebecca Hall