Book Review: Jan Kerouac’s “Baby Driver” — Storming Down the Road

By David Daniel

Baby Driver is a book in the tradition of American road literature, but it moves at a distinctly different pace.

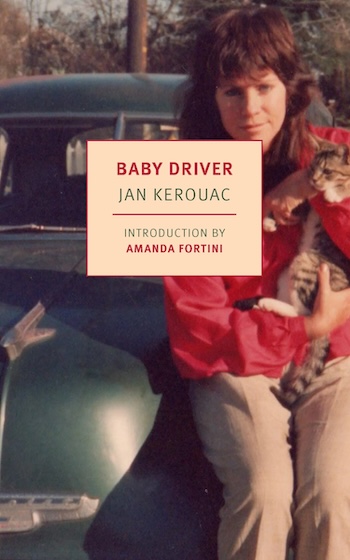

Baby Driver by Jan Kerouac, with an introduction by Amanda Fortini. New York Review of Books Press, $17.95

Near the end of On the Road, the book’s narrator, off the road at last, is back in New York City. One night, trying to locate a party, he calls up to an open window and a pretty girl looks out and invites him up for hot chocolate. “So I went up and there she was, the girl with the pure and innocent dear eyes that I had always searched for…. We agreed to love each other madly.” It’s a feel-good P.S. after wearying travels.

Near the end of On the Road, the book’s narrator, off the road at last, is back in New York City. One night, trying to locate a party, he calls up to an open window and a pretty girl looks out and invites him up for hot chocolate. “So I went up and there she was, the girl with the pure and innocent dear eyes that I had always searched for…. We agreed to love each other madly.” It’s a feel-good P.S. after wearying travels.

Like much of Kerouac’s work, the incident is a transcription from life, as confirmed in Joan Haverty Kerouac’s 1990 memoir Nobody’s Wife. But the real-life marriage between 28-year-old Kerouac and 20-year-old Haverty (“this unhappy interval in both our lives”) was far from storybook. In less than a year it was over, with Haverty pregnant, and returning to live with her mother. The fruit of the relationship was a daughter, Jan, whom Kerouac would never fully acknowledge, and who, in 1981, not yet 30, would publish a novel, Baby Driver, reissued this month by New York Review of Books Press. For an epigraph, Jan Kerouac chose Paul Simon’s song of the same name, though on reflection its lightness is darkened with intimations that her inheritance — a disavowing father — shaped her destiny.

The chapters alternate between memories of childhood (a runaway, juvenile detention homes, a pregnancy at 15 resulting in a stillbirth, Bellevue) and reports on adulthood (a pharmacopeia of drugs, pinballing travel, working as a prostitute). As the gaps between the two narrow, eventually converging, the narrative becomes like watching one of those dashcam video reels of car crashes. Yet what also emerges are flashes of self-knowledge. And a marked freshness of voice: “Deirdre and I forged north, having a festival of beer and junk food along the way in a raunchy delight of careless car existence, drunkenly munching out of crinkling plastic as dry and dusty sceneries swerved by.”

A subtly discernible Beat DNA runs throughout the prose: neologisms and startling juxtapositions (“fruitpeel sidewalks” / a maid’s “insectish shuffle,” being in a mother’s “apronish shadow”). It’s the kind of wordsmithery her father was so deft at, but it would be a mistake to think that her style is an attempt to mimic his. Hers is sharper-eyed, edgier, bearing little of the lyrical sensibility that feather-edges even the starkest of Jack’s writing. One scene, in which she manages to escape from a lover who reveals himself to be menacingly psychotic, is tense as a thriller. And, where his best work intimates an approach to the divine, hers maintains a hard shell, what Amanda Fortini in her introduction calls an “eerie sangfroid.” At one point the narrator is drawn toward the sacred mystery of Catholicism, but rationality prevails and she rejects the experience.

Baby Driver is a book in the tradition of American of road literature, but it moves at a distinctly different pace. Walt Whitman sauntered, John Steinbeck meandered, and Jack Kerouac drifted. Jan Kerouac storms. She is not merely shambling after the “mad ones”: she is one of them, rushing from place to place, person to person, happening to happening. It is exciting at first, like a series of screen captures snapped from a speeding car. Even the fringiest characters are sharply etched. But soon they are gone, swept away in the slipstream as the protagonist skedaddles; the tale takes on an aerodynamic thrust that makes it hard for a reader to get a handhold. Which may have been Kerouac’s intent; she was, by her own account, mind-fogged much of the time. But, as the journeying continues, there’s an exhaustion of spirit despite her youthfulness, glimmers of a thwarted longing to form lasting personal connections.

The strongest bond in the book is between the control-resistant Jan and her heroic, free-spirited mother. They lock horns but their affection endures. Jan only saw her father two times. The first was as a child, when she and her mother went to seek child support (“I couldn’t take my eyes off [him], he looked so much like me. I loved the way he shuffled along with his lower lip stuck out”). The final time, which was when she was grown, occurred when she sought him out in Lowell. By then, Jack Kerouac was a pathetic figure, ensconced “in a rocking chair about one foot from the TV, upending a fifth of whiskey and wearing a blue plaid shirt. He was watching The Beverly Hillbillies.”

In Jack Kerouac’s loutish resistance to parenthood, one sees panic, a man frightened by having birthed something so unlike anything he had brought forth from his imagination. Fear, too, at the threat parental responsibilities would pose to his creative cocoon. Could the man who, rather than changing sheets of typing paper, chose to write OTR on a teletype scroll, embrace the idea of changing diapers?

Jan characterized Baby Driver as fiction, but the book carries a strong flavor of memoir. Actual character names have been retained, including Jan’s own. And the plot is thin, haphazard. Fortini suggests, perceptively, that a way to deal with the dichotomy between fact and fiction is to place the novel in the tradition of the picaresque. What we have here is an artfully written, semi-autobiographical novel with a protagonist who, despite the harsh vagaries of her life, never plays victim or casts blame, and displays unflagging resilience.

As a writer, Jack Kerouac achieved something few literary artists ever do, and some of the heavy cost for the achievement was paid by his family. But the life lived and written about here is Jan’s alone and, in the end, Baby Driver deserves to be judged on its own merits — and as a poignant pointer to where her impressive talents might have taken her.

Note: Jan Kerouac published two more books, Train Song (1988) and, posthumously, Parrot Fever (2005). She died in 1996 at age 44 of complications from liver failure. She is buried in Nashua, New Hampshire.

David Daniel is a novelist and contributor to The Arts Fuse and The Boston Globe. He is a former Jack Kerouac Visiting Writer in Residence at the University of Massachusetts, Lowell.

Intriguing and insightful.

Well-written, as always, in that Daniel style of writing. Clear, crisp, rhythmical.

I was reminded of the sins (and blessings) of the father remain.

Thumbs up.

Great review.

I heard about this book when it was first published, but I was never tempted to pick it up. Until now.

A trove of sharp insights here that enlarge and deepen our view of a great writer from Kerouac-savant Dave Daniel. Tracing the sad tragic cost of the high, Post-Beat road toll, Daniel deftly unearths glints of gold in daughter Jan Kerouac’s work. Now I will approach rereading this virtual Father and Child reunion in a new light.

Another wonderful review. One who is confronted by a paradox of rationality and lets go and drifts into “the sacred mystery of Catholicism” sees the world and the layers of possible worlds through that mystery. If the past, present, and future coexist like particles of wind, maybe David Daniel’s words ride the wind to a fellow writer and in some way are changing her path.

i always learn more in Dave Daniel’s reviews about people, places and things, like writing, than from other reviewers who avoid “tangents.”

Thank you, everyone who responded. Your comments enlarged my understanding of the book and its author.

“And once upon a pair of wheels

I hit the road and I’m gone…”

Yep—Jack, Jan, and the rest of us—right behind.

Well done Dave.