Visual Arts Review: The Spirit and the Street — Allan Rohan Crite’s Portrait of Community

By Lauren Kaufmann

As an artist, Allan Crite was always observing, drawing, and thinking about his Boston — the buildings, streets, parks, and playgrounds of Lower Roxbury and the South End.

Allan Rohan Crite: Urban Glory at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston, on view through January 19, 2026

Allan Rohan Crite: Griot of Boston at the Boston Athenaeum, on view through January 24, 2026

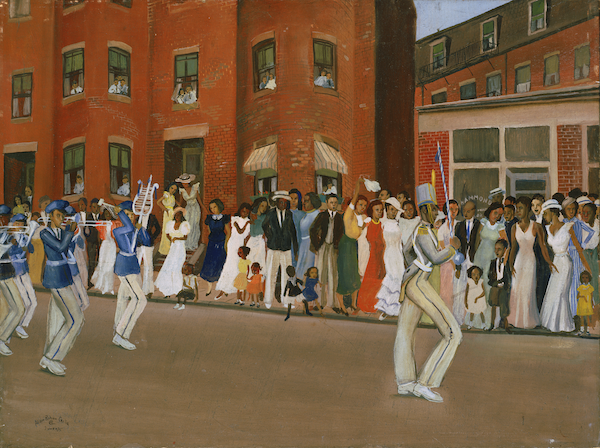

Parade on Hammond Street, June 1935. Courtesy of the Allan Rohan Crite Research Institute and Library. Photo: courtesy of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum

Allan Rohan Crite (1910-2007) was a consummate artist and storyteller. Devoted to telling stories about the everyday lives of his community, he specialized in detailed depictions of quotidian life: a well-dressed couple strolling across a snowy cityscape, children frolicking in a spray of water; commuters bustling outside a trolley stop; a marching band strutting down the street; a choir singer preparing to perform from a church balcony.

What distinguishes Crite’s work is that most of the people that he depicted are Black. Although he was well-known in Boston’s Black community, Crite may be unfamiliar to many. For the next three months, Bostonians will be fortunate to get to know him and his work through two concurrent exhibitions at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum and at the Boston Athenaeum.

Both shows underline the expansive breadth of Crite’s work. The Gardner exhibition is the first retrospective of Crite’s work; it includes paintings, drawings, prints, watercolors, books, and lithographs. The exhibition at the Athenaeum concentrates on Crite’s role as griot, an African storyteller who preserves his village history and retells it through stories, poems, or in Crite’s case, artwork.

There’s no question that Crite was a gifted storyteller. His work revolves around the lived lives of Boston’s Black community — its churches, neighborhoods, parks, and parades. Over the course of his long career, Crite used his artwork to reflect on the changes that took place in the city, particularly those that came from urban gentrification, transformations that displaced many city dwellers, including Crite and his mother.

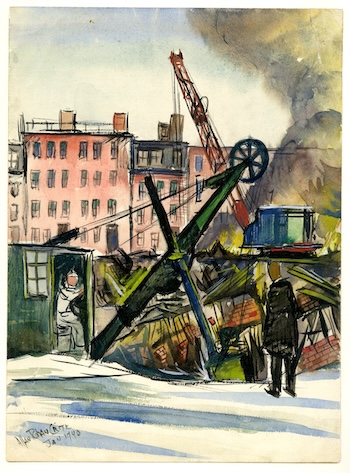

Burning and Digging, South End Housing Project, January 1940. Courtesy of the Allan Rohan Crite Research Institute and Library. Photo: courtesy of the Boston Athenaeum

In Burning and Digging: South End Housing Project, January 1940, on display at the Gardner, Crite looks at how his neighborhood is being demolished. In this case, the project was one of the first of many government-sponsored efforts to provide housing for low-income Black families. This is one of many magnificent watercolors on display in both exhibitions.

Crite was always observing, drawing, and thinking about his Boston — the buildings, streets, parks, and playgrounds of Lower Roxbury and the South End. Through his paintings, drawings, and prints, Crite celebrated community life, elevating everyday events and activities by intently recording them. There are identifiable landmarks that place Crite’s work squarely in Boston, but most of the scenes are from a distant past, a time when people dressed up to go out. Many of his paintings date from the 1930s and ’40s, a time when men and women sported hats in public, and women wore skirts and dresses.

Crite stopped painting in 1950, turning his attention to making prints, which he believed would reach more people than his paintings. In 1955, Crite purchased a lithography press that he set up in his home. Initially, he used it to print church bulletins. The press turned out to be a reliable workhorse, serving the artist for 30 years. Over the course of his career, he used his Multilith press to create numerous prints and lithographs, some of which he colored by hand.

Crite was a devoted member of the Episcopalian church, and the role of religion is central to much of his work. In addition to painting scenes of church interiors, Crite illustrated a book — Three Spirituals from Earth to Heaven. He painted many religious scenes, including some that infused spirituality into city life. Streetcar Madonna, 1946, shows a Black Virgin Mary riding the T with a young Jesus. In this watercolor, Crite uses bright colors and black ink to depict the riders, who appear unaware of their spiritual companions. The artist seems to be hinting that the religious and secular live side-by-side, and that we fail to recognize the spiritual who walks among us every day.

Streetcar Madonna, 1946. Courtesy of the Allan Rohan Crite Research Institute and Library. Photo: courtesy of the Boston Athenaeum

The new wing at the Gardner offers curators an opportunity to stretch beyond the permanent collection, and it’s been inspiring to see how they have been using the space to spotlight modern artists whose work resonates with the museum’s mission. Interestingly, there’s a strong connection between Crite and the Gardner. Growing up in Boston, Crite visited the Gardner often — his mother once met Isabella Stewart Gardner. The exhibition includes a drawing of the Gardner that a young Crite made after visiting the museum.

As an adult, Crite was inspired by Isabella Stewart Gardner’s transformation of her home into a museum, and he set out to replicate her success by trying to turn his home a museum. Unfortunately, Crite faced too many obstacles — both bureaucratic and financial — to realize his ambitious dream. Nevertheless, Crite’s home remained a popular destination for his friends and local Black leaders, who convened to see his artwork as well as discuss the issues of the day. Civil rights activist Ted Landsmark supplies a wonderful statement about the atmosphere of Crite’s home: “Every drawer, every wall, every crevice had some drawing or book that he had produced. And so walking into the house was like walking into a culture that he had created … his vision of what Boston was.” Landsmark was a friend of Crite’s and served as co-curator of the exhibition at the Gardner.

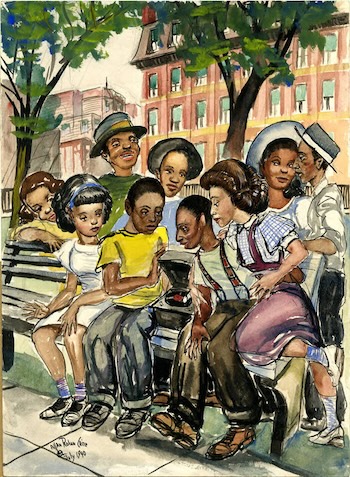

A Course in Music Appreciation, July 1940. Courtesy of the Allan Rohan Crite Research Institute and Library. Photo: courtesy of the Boston Athenaeum

Crite also had a strong connection with the Boston Athenaeum. He exhibited his work there throughout his life and used the library for research. In 1968, the Athenaeum published one of Crite’s pamphlets — Towards a Rediscovery of the Cultural Heritage of the United States. In the ’70s, he donated a significant number of artworks to the museum, including 16 oil paintings, 39 watercolors, and more than 50 drawings. Many of these works are on display in the current exhibition.

A Course in Music Appreciation, July 1940, is a watercolor celebrating the everyday joys of community life. In this scene, a small group gathers together in a park, listening to the music coming from a portable Victrola. The setting is Madison Park, which was ultimately destroyed by urban renewal. The label at the Athenaeum suggests that the grouping includes future State legislator Michael Haynes and his brother, Vinnie. Their brother, Roy Haynes, went on to become a celebrated jazz drummer.

Crite was deeply engaged with the Boston religious and artistic communities. He served as a mentor to up-and-coming artists. John Wilson, whose work was honored in a retrospective at the Museum of Fine Arts earlier this year, testifies to Crite’s influence: “Back in the ’30s in Roxbury when I was about 15 or 16 trying to paint and draw, I found it difficult to even think about the idea of art as a life’s work. There were no black people who made paintings and drawings as serious careers that I had even heard of … until someone told me of Allan Crite.”

Wilson goes on to credit what he calls “a sense of dignified humanity” that Crite conveyed in his work. It is one among a number of significant qualities that make Crite’s work compelling, enduring, and worthy of our attention.

Note: The City of Boston recently recognized Crite’s lasting contribution to the local cultural landscape by naming November 13th “Allan Rohan Crite Day.” The Gardner Museum sponsored a day of special programming, including a panel discussion about urban renewal, with a focus on how the city continues to preserve diverse neighborhoods.

Lauren Kaufmann has worked in the museum field for the past 14 years and has curated a number of exhibitions.

Well written and so interesting! Thank you, Lauren!

Thanks, Charles. We’re so fortunate to have two exhibitions devoted to Crite’s work–ample evidence that his life and work are worthy of our attention. His talent as visual chronicler of Boston’s Black community shines through in both exhibits. I hope that many people get out to see these exhibitions and learn about the crucial role that Crite played for many years.

Thanks for an empathetic and insightful review. Crite was a master too long marginalized in Boston. He was a major influence on the emergence of generations of artists of color. This recognition is long overdue. When Crite was shown at NAGA Gallery i was there when MFA curator Cheryl Brutvan visited. It was telling that she failed to view the work or comment on it to gallerist Arthur Dion. A prior show at the St. Botolph Club occurred during Covid and nobody got to see it.

Another insightful critique from Lauren.