November Short Fuses — Materia Critica

Each month, our arts critics — music, book, theater, dance, television, film, and visual arts — fire off a few brief reviews.

Classical Music

The phrase “The Musicians of the Old Post Road” is a resonant one for anybody who grew up in New England several decades ago. For the sake of younger folks, the ensemble explains on their website that their primary venues “trace the route of the old Boston Post Road, the first thoroughfare connecting Boston and New York City beginning in the 1670s.”

The phrase “The Musicians of the Old Post Road” is a resonant one for anybody who grew up in New England several decades ago. For the sake of younger folks, the ensemble explains on their website that their primary venues “trace the route of the old Boston Post Road, the first thoroughfare connecting Boston and New York City beginning in the 1670s.”

This latest of their, thus far, eight CDs (click here to order) was partially funded by five music lovers named in the booklet and by a Noah Greenberg Award from the American Musicological Society. The result is utterly lovely, and I’m glad (and a bit ashamed) to be getting to know the group for the first time!

The pieces are all little known—some have been edited and published by the ensemble for the first time—and by German Baroque composers: Christoph Graupner (court composer at Darmstadt, one of whose operas was splendidly recorded by the Boston Early Music Festival), Georg Philipp Telemann (with whom Graupner became friendly), Graupner’s student Johann Friedrich Fasch, and Graupner’s patron, Landgrave Ernest Louis, who was highly trained in music (rather like Frederick the Great of Prussia).

The seven pieces (including four by Graupner) are full of surprises. For example, Graupner’s Sonata in G Major (ca. 1741) is for flute or violin, harpsichord (a fully written out part), plus a separate continuo part for whatever instrument or instruments were available to emphasize the bassline.

The musicians here are Suzanne Stumpf (playing a delectable wooden flute), violinists/violists Sarah Darling, Jesse Irons, and Marcia Cassidy, cellist Daniel Ryan (cello), and guest harpsichordist Benjamin Katz. All are alert to shifts in the music’s moods, and to each other’s phrasing, intonation, attack, and occasional light touches of vibrato. The CD is varied enough to be listened to with continuous pleasure and frequent surprise.

— Ralph P. Locke

Felix Mendelssohn may or may not have been as conflicted about his Jewish heritage as some claim. But there’s no question he thoroughly embraced the musical principles of German Lutheranism. A new series from Harmonia mundi promises to highlight this, both in Felix’s music and that of his sister, Fanny: Volume 1 pairs the younger brother’s incomplete oratorio Christus and setting of Psalm 42 with his big sister’s Lobgesang.

Christus’s echoes of its predecessors Paulus and Elias are hard to miss—“Es gibt ein Stern” sounds like a natural choral outgrowth of the latter—though these excerpts are, generally, so fragmented (the shortest lasts only eleven seconds) as to make it impossible to draw conclusions about the merits of the larger work that Mendelssohn’s premature death robbed us of. At any rate, the performance from soprano Christina Landshamer, tenor Martin Mitterrutzner, the RIAS Kammerchor, Kammerakademie Potsdam, and conductor Justin Doyle is rich, full-bodied, and well-directed.

The collective’s take on Psalm 42 (“Wie der Hirsch schreit”) is, likewise, smartly defined. Schumann admired this score after its 1838 premiere and it’s a wonder the music isn’t more widely recorded and better known. Nevertheless, the present reading does it full justice, especially the achingly beautiful opening chorus.

That Fanny’s output has remained obscure is more the result of misguided social mores than talent, as the Lobgesang makes clear. The beautiful “Introduzione” gives Felix a run for his money in channeling Handel and Bach, while the choral writing is consistently fresh and lively. What’s more, the cantata’s lone aria showcases a keen ear for color, with discreet solos for violin and flute. Doyle and his forces deliver it with a surety, zeal, and understanding that, one hopes, will carry this series—and composer—far into the future.

— Jonathan Blumhofer

Did Franz Josef Haydn ever put a foot wrong, musically? Probably; he was mortal, after all. But the consistency of the man’s invention and his ability to sound fresh and unforced even when working within similar formal and structural constraints remains astonishing. Here was a guy, you come to realize, who, in another time and career track, might have found a way to bring transcendence to cookie-cutter suburbia.

Or so it seems in this installment (No. 17) of Haydn 2032, the Kammerorchester Basel’s ongoing survey of the Austrian composer’s vast symphonic output. Two of the album’s three symphonies—Nos. 13 and 36—follow the familiar four-movement pattern; No. 13 takes the old, three-movement pattern. So does the Violin Concerto No. 1.

How did Haydn manage to avoid becoming (or, at least, sounding) repetitious in this context?

Textural and gestural variety for one. Take the opening movement of the Thirteenth Symphony, with its prominent wind-and-brass pedal points and trills accompanying tautly pulsing string figurations. Or the Violin Concerto’s beautifully inward Adagio, with its songful solo line floating over a serenade-like bed of pizzicato strings.

Even when Haydn did repeat himself, as in the solo writing during the slow movements of the Symphonies Nos. 13 and 36, the scope and affect he was after in each were completely different. In the former, there’s a short, sweet dialogue between violin and cello, whereas the latter emerges as a deeply searching aria.

Through all of this, the playing of the Basel ensemble, which is led by Giovanni Antonini, is crisp and spirited. Though a period group, there’s a warmth and depth to their delivery of the music’s lyricism that is appealing. Dmitri Smirnov dispatches the Concerto’s solos with a gracefulness that isn’t afraid to show its teeth, especially in the first movement’s double stops.

— Jonathan Blumhofer

Books

The son of a steelworker, Kevin McIlvoy, or Mc as he preferred, turned at age twenty from steelwork to a life in literature—reading widely, publishing ten volumes of prose and poetry, and discovering his extraordinary gift for teaching. ‘Teaching’ hardly does justice to Mc’s approach. During decades helping to shape, among other institutions, the Warren Wilson MFA Program, he led obliquely, by analogy and paradox and humor. The aim was to free his students to hear the voices in their heads, instead of the critics and rule-mongers outside, i.e., ‘learning by the agenda.’ To trust in their work’s ultimate purpose, however meandering or awkward early drafts might seem.

The son of a steelworker, Kevin McIlvoy, or Mc as he preferred, turned at age twenty from steelwork to a life in literature—reading widely, publishing ten volumes of prose and poetry, and discovering his extraordinary gift for teaching. ‘Teaching’ hardly does justice to Mc’s approach. During decades helping to shape, among other institutions, the Warren Wilson MFA Program, he led obliquely, by analogy and paradox and humor. The aim was to free his students to hear the voices in their heads, instead of the critics and rule-mongers outside, i.e., ‘learning by the agenda.’ To trust in their work’s ultimate purpose, however meandering or awkward early drafts might seem.

McIlvoy died, unexpectedly, in 2022. Now Christine Hale, his widow, has compiled a graceful selection of his writing and lectures. A gift for the legion of writers he taught, as well as new and experienced learners everywhere. Willingness: a Writer’s Meditations on Crossing the Flood (WTAW Press) doesn’t offer the usual set of craft chapter headings—place, character, dialogue plot, etc.—in fact Mc had little respect for plot. Instead, the grouped topics are introduced by suggestively inverted koan. For example: Inviting overwhelming engagement, estrange. Inviting overwhelming estrangement, engage.

At 246 pages, the book is not long. But there is plenty to linger over, and reread. Willingness is almost as much a guide to the examined life, driven off McIlvoy’s own struggles with his art, as it is to fearless writing. Vivid metaphors in particular, verging on fables, illuminate rather than preach.

At his desk, “I watched a really large wasp fly into a really small spider’s flimsy made-for-flies-and-gnats web […] The wasp would have escaped pretty fast but the spider hurriedly added webbing to the area near the wasp’s wingtips, and it hurriedly tore down and re-rigged other parts of the web structure, and it meticulously firmed up the little bit of webbing limiting the movement of the wasp’s head, and it very slowly crawled into the basement of the web in order to wrap webbing around the tip of each wasp leg. At all points in this pleasurable working and crafting, the spider, about one-twentieth the size of the wasp, paused, started again, stepped back, started again, paused. I could hear it say to the wasp, “Staying long? Of course you are…of course you are.”

Or this: “A person who wants that unique sound of John Lee Hooker on a song like “The Waterfront” or “Stop Now Baby” will want a guitar that in open tuning has a crunch-huh-howl whenever the F# is fingered on any fret. That flawed wonder is called the “wolf tone,” and it is characteristic of other kinds of stringed instruments. Some cellists choose to correct it with a “wolf tone eliminator” or “wolf suppressor” placed between the bridge and the tailpiece. […] the restorer Ken Meyer says, “the better the instrument is adjusted, the worse the wolf shows. When the instrument is not well adjusted, all the pitches are wobbling. There’s no ring while you play and the harmonics are off pitch. This can hide the wolves or make for just general wolfy areas.” Mc’s point? “to make distinctions between work that we might name as “unconventional” and work we might name as “experimental,” it is worth considering the degree to which the artist has altered the instruments toward dynamic balance and away from equilibrium.”

Alas, no room here for the shitbasket metaphor, or the boat, or the Eternally Returning Biscuits.

Were it only as a smartly annotated MFA reading list, Willingness would merit enduring shelf space. Tolstoy, Baldwin, Baxter, Kundera, Thoreau, Livesey, Robert Nozick, Alfred Lord Whitehead… these are a few of the fifty or more authors quoted and/or cited.

Not everyone will be fully on board with McIlvoy’s manifesto: “I believe a manuscript represents a dynamic convergence of the author’s will, the will of the work itself, and the will of the reader.” That said, who would argue with the wisdom hinted at in the subtitle? The full quote, in the epigraph, comes from the Discourses of the Buddha:

How, dear sir, did you cross the flood?

By not halting, friend, and by not straining I crossed the flood. When I came to a standstill, friend, then I sank; but when I struggled, then I got swept away. It is in this way, friend, that by not halting and by not straining I crossed the flood.

— Kai Maristed

I feel like a party pooper for not joining the ravers about this new “wise,” “exuberant,” and “inspiring” memoir, Susan Orlean’s Joyride (Avid Reader Press/Simon & Schuster, 368 pages), but I found myself thinking of blurbs you never see on a book cover, like: “pleasant,” “uncompelling” and “really?”

I feel like a party pooper for not joining the ravers about this new “wise,” “exuberant,” and “inspiring” memoir, Susan Orlean’s Joyride (Avid Reader Press/Simon & Schuster, 368 pages), but I found myself thinking of blurbs you never see on a book cover, like: “pleasant,” “uncompelling” and “really?”

The author of seven well-researched and very popular books of non-fiction – The Orchid Thief, Rin Tin Tin,and The Library are three – has written a hybrid memoir: part autobiography; part writing manual, and part stories behind her article ideas – for the alternative Willamette Weekly in Portland, Oregon and Phoenix in Boston; and then Esquire, Rolling Stone, Vogue, and The New Yorker magazines.

Born in 1955 and raised in Shaker Heights, Ohio, Orlean (her Polish-Jewish paternal grandfather changed the name from Orlinski) was the third child of a lawyer/ real estate developer and his homemaker wife who dreamt of being a librarian. Orlean identified with her adventuresome red-headed father and, in a rare piece of self-observation, notes, “Being a redhead is more than a mere description. It is a way of being in the world. You stand out. You’re noticed. You’re a minority of a minority, listed for extinction…” She doesn’t delve into how she feels about this – her sharp, reportorial eye seems averse to looking at herself. Even when she includes a memo from a book editor describing her as “32-year-old redhead, Talk of the Town regular….” She doesn’t comment.

In Orlean’s telling, her productive career is due to her life-long ambition to write, her friends, and her luck. In 1977, after earning her BA at University of Michigan, she followed her boyfriend to Portland, Oregon where a friend tells her about new magazine start-up, the Paper Rose. In 1985, another friend finds her an agent. Another tells her the New Yorker needs new writers for Talk of the Town because in the wake of William Shawn’s firing and Bob Gottlieb’s hiring many left. “This was shocking,” she writes in one of her best one-liners. “It was as if the Vatican had put a listing for Cardinals on Craigslist.” One idea she pitches to editor Charles McGrath is “How Benetton stores train their staff to fold sweaters precisely.”

Joyride features writing tips for beginners, accounts of two marriages, living in Ann Arbor, Portland, Boston, New York, and L.A. as well as on a farm in the Hudson Valley, working with excellent editors, and having a book adapted into a movie with herself played by Meryl Streep. It ends with the California fires of 2025. This hybrid memori could have been “Riveting!” had it probed a bit below the surface. Instead, it mostly reads like a witty travelogue.

— Helen Epstein

Jon Fosse’s Vaim (Translated by Damion Searls, Transit Books, 134 pages, $25.95), his first work since winning the 2023 Nobel Prize in Literature, is a ghostly story about imposed domestic relationships that hovers in a Samuel Beckett-inflected realm. Dream and reality interweave; individuals acquiesce to their fate; isolation is a casually accepted fact of life. The thoughts of these working-class narrators are conveyed through long, trampolining sentences held together by commas, their rhythms expertly engineered by translator Damion Searls.

Flickers of Krapp’s Last Tape run through the first and longest of the three interlinked narratives, each told by an emotionally repressed middle-aged male in a rural Norwegian fishing village. Jatgeir, a man with few friends and no family, is seen by a long-lost love who asks him to rescue her — without delay — from a marriage she no longer can bear. (She is Eline, the namesake of Jatgeir’s treasured boat.) What starts out as a wry farce, Jatgeir’s search for a needle and thread to fix a button (he is overcharged — twice), suddenly becomes a gracious drama in which a memory of longing is redeemed.

The narrator of the next section, Elias, was Jatgeir’s only friend. A religious type, he drew away from Jatgeir after Eline came to live with him because the pair never married. One day, Elias is visited by Jatgeir — apparently, after the man has died. The apparition — true or false? — inspires reassurance rather than fright, a sense that Jatgeir is with Elias in a way that he had never been before: “… with a kind of joy he says it is good here, and I, walking up the road in Vaim, I raise my hand and wave at the sky, at where I think Jatgeir is, and everything feels right…”

The final story is told by Frank, Eline’s estranged husband. She came back to him after Jatgeir died, and he accepted — without demur — her no-nonsense invitation to move into Jatgeir’s home with her. Why? He isn’t quite sure, aside from the fact that Eline was a force of nature who could not be denied. “Everything was strange,” he thinks to himself, considering putting that thought on his tombstone. The first in a trilogy, Vaim is a poignant testament to the undeniable demand for comfort.

— Bill Marx

Jazz

Just… Quinn & Barrett, the latest release from New Orleans-based Anna Laura Quinn and Ed Barrett, succeeds as a difficult duet of singer and guitarist: the vocalist has range and appeal and never becomes dull, and the guitarist carries the swing of an entire rhythm section. Quinn has a voice from a bygone era with contemporary phrasing. She’s a bit like a dialed-down and less world-weary Rickie Lee Jones. Guitarist Barrett is from the Kenny Burrell/Joe Pass school, creative but no-nonsense.

“Everybody Wants to Rule the World” is pretty much a jazz standard now, and why not? It has great harmonies, tricky intervals, and built-in syncopation that easily swings (even at this slow tempo) if you just give it a tap. “A Flower is a Lovesome Thing” is another ballad, and Quinn doesn’t oversell it with histrionics. Barrett is right there, speeding up and slowing down along with her, always implying the steady pulse.

“Walkin’ After Midnight” asserts Quinn’s New Orleans cred, and “Plus Je T’Embrasse” shows off her beautiful French accent in high lilting voice. “Just One of Those Things” has Barrett swinging a walking bassline on the intro, and when Quinn scats, they sound like one of those Joe Pass and Ella Fitzgerald sessions on Pablo. It’s also a treat to hear all the juice Quinn can squeeze out of a blue note on “Dreamer’s Ball.”

Two stand-out tracks are the blues “Aged and Mellow,” which Quinn resists turning into a New Orleans raunchy grind for the tourists. She and Barrett build it up and gently put it down. I like their version of “Blue Motel Room” better than Joni Mitchell’s original—it’s sadder, less cute, and more real.

Easily worth a download and a tip on Bandcamp.

— Allen Michie

So, you think you like drums? You must check out Live in Saint Louis, Senegal recorded in 2024 by a combined group led by French drummer Raphaël Pannier and Senegalese percussionist Khadim Niang.

So, you think you like drums? You must check out Live in Saint Louis, Senegal recorded in 2024 by a combined group led by French drummer Raphaël Pannier and Senegalese percussionist Khadim Niang.

The recording teams a contemporary jazz quartet with an eight-piece percussion ensemble which practices a popular form of West-African drumming known as Sabar. The proceedings may, at times, come off as jazz with an expanded percussion section (or vice versa). But, when things come together, the musicians move toward inspired interplay.

“Sine Saloum” bridges cultural gaps, connecting strands of melody and harmony with percussive drive. “Hommage to Doudou N’Diaye Rose,” a tribute to another Sabar master, is a full-tilt drum effort that invites your eardrums to join in.

Recognizable tunes (to jazz fans) like Ornette Coleman’s “Lonely Woman” and Dave Brubeck’s “Take Five” (a composition that Niang reportedly viewed as an important challenge for his group) feature stellar contributions from saxophonist Yosvany Terry. Keyboardist Thomas Enhco and bassist François Moutin also push and pull through the contours of these two masterful compositions. The result is an exciting set of live music.

— Steve Feeney

Popular Music

Though Colombian DJ/producer CRRDR has been working for several years, in 2021 he began posting his edits on SoundCloud, and with his debut album Latincore Legend (Traaampaaa) he is firming up his presence in international club music. At 88 minutes, the recording has got room to sprawl, and it features countless singers and rappers. A testament to his tremendous productivity: he dropped the mixtape Parental Advisory Perreo Content in September.

Though Colombian DJ/producer CRRDR has been working for several years, in 2021 he began posting his edits on SoundCloud, and with his debut album Latincore Legend (Traaampaaa) he is firming up his presence in international club music. At 88 minutes, the recording has got room to sprawl, and it features countless singers and rappers. A testament to his tremendous productivity: he dropped the mixtape Parental Advisory Perreo Content in September.

The opening track in Latincore Legend has Miss Bashful moaning and smacking her lips as she sings “Friki.” As hard as the drums pummel away, her vocals remain breathy. Latincore Legend makes good use of sonic whiplash, often contrasting sounds within songs. A distant, authoritative male voice intones like a radio DJ throughout.

CRRDR changes the moods in his songs by speeding up the drums, chopping up vocals, treating words as if they were percussive weapons. The “core” in “Latincore” refers to his creation of a speedy, heavily electronic version of various Latin rhythms. He’s devoted to decolonizing club culture, placing Caribbean and South American genres like dembow, guarancha, neoeperreo, and reggaetón alongside techno.

Some of Latincore Legend’s tracks manage to sound gentle and hard simultaneously. “Papi Duro” accomplishes this feat by breaking away from rolling drums — to which the word “papi” is glued — into a middle section of vocals and synthesizer. Rather than clinging to a 4-on-the-4 beat, the percussion continually evolves.

Latincore Legend doesn’t feel as though it was made to be heard in one sitting. This is not a cohesive album; it comes off as more of a playlist that has been made to be cut up — a collection of “weapons” for club DJs. The music successfully demands attention on its own, it also works as a backdrop, quick doses of stimulation. One song even confesses: “sorry but the Latincore stays on during sex.”

— Steve Erickson

Holy Sons’ Puritan Themes (Thrill Jockey) gives off an old, smoky aura, as though it had been a private press album dropped off at a thrift store in 1972. The one-man project of Emil Amos, the recording wrestles with molten shards of folk, country, and classic rock, forcing them into a dense, chaotic whole.

Some of the instrumentation on Puritan Themes is discernible, especially Amos’ resonant acoustic guitar. But most of the rest of the instruments have been distorted into an indistinct fog. For example, the finale of “Raw & Disfigured” abandons the song for distant static. A more professional mix would have insured listeners could make out the instrumentation, but Amos is not interested in clarity. He mutters and mumbles his way through “Stand Up Straight Again.” Coherent phrases leap out and then disappear in “Radio Séance.”

Puritan Themes’ opacity suggests that is a private, deeply personal project. Looking back to the time when indie artists began to embrace folk and classic rock, it sticks to an outsider ethos. The nearly instrumental “Radio Séance” treats samples of vocals and guitar as guides through a maze of grief. It rings out with immense feeling, drawing on the traumatic life experiences of a man who began using drugs daily as a teenager and later worked for 13 years at a homeless shelter.

Despite the haziness of the sound, a hidden discipline underpins Puritan Themes. “Chain Gang” longs for optimism, without quite finding it: “this is our world to celebrate the flames/I push on but the weather remains the same.” The ‘70s references aren’t nostalgia; rather, they’re a reminder that the nightmares of American life began long ago. (As well as suggest an alternate past, where Crosby, Stills & Nash-style soft rock evolved into a more experimental style.) Making music this cluttered and ambiguous mean something — it is very hard work. But Puritan Themes pulls it off.

— Steve Erickson

Visual Art

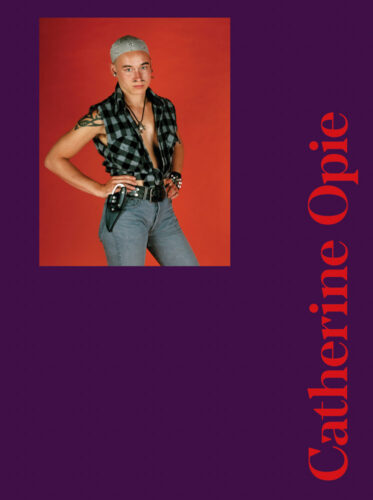

During the Culture Wars of the ’90s, photographer Catherine Opie came to national prominence with her images of leather dykes along with self-portraits that featured cutting and piercing. She quickly joined an iconic pantheon that included Robert Mapplethorpe’s pictures of erotic deviance and Nan Goldin’s diaristic slideshows. Her art became collected and shown world-wide.

During the Culture Wars of the ’90s, photographer Catherine Opie came to national prominence with her images of leather dykes along with self-portraits that featured cutting and piercing. She quickly joined an iconic pantheon that included Robert Mapplethorpe’s pictures of erotic deviance and Nan Goldin’s diaristic slideshows. Her art became collected and shown world-wide.

In 2024, Opie had her first solo exhibition in Brazil at the Museu De Arte De São Paulo Assis Chateaubriand. Sixty-six of her photographs (taken between 1987 and 2022) were placed in lively dialogue with twenty-one classical oil portraits from the museum’s collection. This sly curatorial conceit not only highlighted how Opie’s opulent compositions fit into art history — it underscored the varied ways she celebrates unsanctioned queer desire.

Catherine Opie: Genre/Gender/Portraiture (KMEC Books, 176 pages, $45) documents the Brazilian show, pairing her resplendent photos with the complementary paintings. Insightful essays discuss Opie’s indispensable contribution to queer representation, examining her performative staging of such topics as gender, taboo, and the social construction of identity.

Also included are color saturated prints of actor Elliot Page, singer Justin Bond, swimmer Diana Nyad, and performance artist Ron Athey, along with less formal black and whites from Opie’s Girlfriends series. Leather gendernauts are amply represented, pictured with tattoos, piercings, fake mustaches, costumes, and fetish gear, along with pictures of settled lesbian couples at home.

Opie’s provocative self-portraits from her early years are also included. In Self-Portrait/Cutting (1993), the focus is on a crude drawing carved into her back of two female stick-figures — the etching’s contours are still bleeding. Opie wears a black hood in Self-Portrait/Pervert (1994) — there are needles in her arms, the word “Pervert” carved in oozing letters across her bare chest. Goya’s Portrait of Fernando VII is paired alongside this picture.

The harshness of some of these photos is counterbalanced by the sweetness of such images as Self-Portrait/Nursing (2004). Here. Opie gazes lovingly at her son as she breastfeeds him. This image is ingeniously matched with Bellini’s The Virgin with Standing Child.

– John R. Killacky

Artist Jorg Van Daele working on his sculpture. Photo: Andres Institute of Art

The 25th Annual Bridges and Connections Sculpture Symposium at the Andres Institute of Art (Big Bear Mountain, Brookline, NH) included a keynote speech by an award-winning community activist/comic book artist/educator, an introductory presentation of this year’s sculptor fellows’ portfolios, celebratory community meals, concerts, a panel discussion by three previous fellows, and opening and closing (including sculpture unveilings) ceremonies.

Unlike other years, there were ridiculous difficulties with an international visa issue. Regretfully, a previously invited artist from India was not able to attend, thanks to unwarranted resistance from our State Department. The three 2025 participating mid-career artist fellows were Parastoo Ahovan, formerly from Iran and now living in Connecticut, Robert Leverich of Olympia, Washington, and Jorg van Daele of Kalmthout, Belgium.

During their three-week residency, each sculptor created a permanent addition to the existing 104-piece collection on the site.

Parastoo Ahovan is a multimedia artist who grew up in Iran where she received her BFA. Moving to the US, she studied at Pratt and Boston University for her MFA. Her piece at AIA combines metal and granite and is entitled Intervention. It boldly suggests a comet intersecting with a structure or the piercing of a hard membrane by a porous particle.

Robert Leverich is trained as an architect, craftsman, and sculptor. Each of his works are thoughtfully elegant and often gracefully detailed. Robert’s artwork at AIA is entitled Gnomon, a reference to a sundial’s shadow-caster. The sculpture investigates the notion of time–present and past, permanent and fleeting.

Jorg Van Daele’s work is distinguished by how he puts different structures into his sculptures. They look as if they had been fabricated with several separate stones. But that is an illusion: his sculptures are mostly made of one meticulously carved single stone. At AIA, his evocative sculpture Peace Decisive Piece deftly demonstrates this ingenious technique.

— Mark Favermann

Television

Toni Collette in Wayward. Photo: Netflix

Wayward (Netflix) This Canadian thriller series, created by comedian/actor Mae Martin, starts off promisingly. Two Toronto high school students, Abbie (Sydney Topliffe) and Leila (Alyvia Alyn Lind), spend their days smoking weed and skipping classes. When Abbie’s parents ship her off to Tall Pines Academy in Vermont, a private school for troubled teens, Leila hitches there to break her out. She ends up being “admitted” to the facility, which seems more like a prison than a school, complete with corrupt “guards” and a tense social order. Meanwhile Alex (Martin), a police officer and transgender man, moves with his pregnant partner Laura (Alias Grace’s Sarah Gadon) to the town of Tall Pines, where Laura was once a student.

If it sounds like a riff on Twin Peaks, well, the town is indeed a strange place, with no small children and no crime. The school is run by a cult-like founder (Toni Collette) who uses questionable techniques to get students to mend their ways. When Alex is called to the school to investigate a missing student, Abbie begs him for help, and the cop commences a covert effort to investigate further. Local police chief Dwayne (the excellent Brandon Jay McLaren, seen in The Killing) treats Alex as a friend, but he seems determined to hide the town’s rather dark secrets. Meanwhile, Laura is mired in past trauma, and exploiting pain is seemingly what Tall Pines Academy is all about. It’s all fairly suspenseful and weird, with superior performances throughout, especially by the young actors playing the students. Unfortunately, the compelling story wraps up a bit too quickly and neatly in an contrived, unsatisfying finale.

— Peg Aloi

Tagged: "Catherine Opie: Genre/Gender/Portraiture", "Into the Light", "Just… Quinn & Barrett", "Live in Saint Louis Senegal", "Puritan Themes", "Vaim", "Willingness: a Writer’s Meditations on Crossing the Flood", Andres Institute of Art, Anna Laura Quinn, Christina Landshamer, Christoph Graupner, Ed Barrett, Emil Amos, Giovanni Antonini, Holy Sons, Jon Fosse, Jorg Van Daele, Joyride, Justin Doyle, Kammerakademie Potsdam, Kammerorchester Basel, Kevin McIlvoy, Khadim Niang, Martin Mitterrutzner, RIAS Kammerchor, Raphaël Pannier, Robert Leverich, Susan Orlean