Book Review: India Through a Daughter’s Eyes: The Turbulent Journey of “Mother Mary Comes to Me”

By Helen Epstein

This account of a formidable mother and equally formidable daughter is an absorbing read that packed the memoir form to the gills and demanded my attention.

Mother Mary Comes to Me by Arundhati Roy. Scribner, 352 pp.

If you have never read Arundhati Roy, this book is a good place to begin. Like her fiction, it features a dazzling and large cast of characters, locales, terms, and references unfamiliar to non-Indian readers and is set in “India’s strict grid of caste, religion, gender, and ethnicity.” But Mother Mary Comes to Me is a mostly straightforward, chronological memoir. Roy’s story is dramatic and occasionally self-dramatizing; her writing, a seductive blend of hawk-eyed description, polemic, and commentary. Though I would have welcomed a map and a glossary, I found this account of a formidable mother and equally formidable daughter an absorbing read that packed the memoir form to the gills and demanded my attention.

Taking its title from the Beatles song “Let It Be,” Mother Mary Comes to Me recounts the author’s relationship to her heroic single parent. After Mary’s death at 89, Roy writes, “Perhaps even more than a daughter mourning the passing of her mother, I mourn her as a writer who has lost her most enthralling subject. In these pages, my mother, my gangster, shall live. She was my shelter and my storm.”

Controversial journalist and activist, author of two best-selling novels, many political essays, and nine books of nonfiction, Arundhati Roy takes on many subjects and themes: two super-strong Indian women and the dynamics between them; the relations between Indian siblings, spouses, generations, sexes, classes, and ethnic groups; the trauma of intergenerational family violence; the legacy of colonialism and importance of the English language; neo-imperialism; the persecution of indigenous people, Sikhs, and Muslims; dams and the environment; free speech; patriarchal norms; and the never-ending war in Kashmir. “India, my dear,” is her ironic, recurrent refrain.

Mother Mary Comes to Me also serves as a sourcebook for Roy’s prize-winning novel The God of Small Things. Its protagonist, Ammu, is modeled on Mrs. Roy. The Imperial Entomologist is Arundhati’s grandfather. “Obviously he was an enthusiastic collaborator with the colonial government,” Roy writes, “and took the Imperial part of his designation seriously.… he whipped his children, turned them out of the house regularly, and split my grandmother’s scalp open with a brass vase.” Arundhati’s uncle G. Isaac stars as Chacko, a Rhodes scholar and Marxist who models failure to his niece by running a pickle, jam, and curry-powder factory in the family home. Both mercurial personalities, Mrs. Roy and G. Isaac help and brutally harm each other till their deaths. Arundhati is, among many other things, an heir of severe family trauma.

After Mrs. Roy reads the book, she asks how Arundhati could remember abuse and arguments that had occurred when she was so young. “Most of us are a living, breathing soup of memory and imagination,” is her reply, “and we may not be the best arbiters of which is which.” Mother Mary Comes to Me, it occurred to me more than once, would be useful reading for psychotherapists.

Susanna Arundhati Roy was born in 1961, the second child of Rajib Roy from Calcutta and Mary Roy from the village of Ayemenem in Kerala. In her brief sketch of the couple, she implies that they were from privileged families. He was a Bengali working as an assistant manager on a tea plantation in Assam and an alcoholic. She was a college graduate from an upper-caste, Keralian Syrian Christian family, who married in order to get away from her abusive father. She suffered from asthma, loneliness, and fury at what she saw as the burden of two unwanted children.

In what was a rare and bold move in the early ’60s, Mrs. Roy left her husband and moved her two toddlers — Lalith Kumar Christopher Roy (LKC) and Susanna — into the late Entomologist’s holiday cottage in a hill station in the state of Tamil Nadu. Her brother G. Isaac (with the support of their mother) tried to evict her. Mrs. Roy called the police, claimed squatter’s rights, and resisted eviction until she retreated to her mother’s home in Kerala. This, too, was “a ledge that we could be nudged off at any minute,” the author writes, where even the family cook grumbled about the shamefulness of fatherless children living among “decent” people. Mrs. Roy never forgot or forgave. She persisted. In 1986, the Supreme Court case of Mary Roy v. State of Kerala established equal inheritance rights for Syrian Christian women. In their senior years, she managed to get her brother evicted from the Entomologist’s mansion.

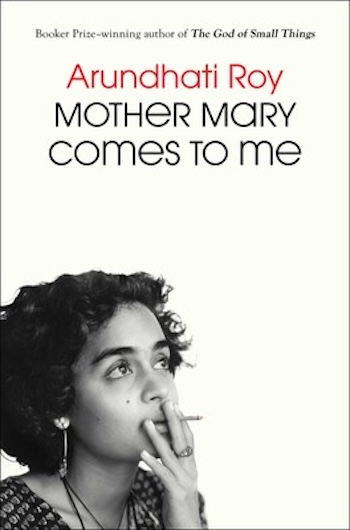

Arundhati Roy. Photo: Mayank Austen Soofi

LKC and Susanna were home-schooled until the ages of 7 and 5 when, with the help of “a middle-aged British missionary lady,” Mary Roy established a tiny school at the local Rotary Club. A talented teacher and administrator, she attracted a loyal staff and so many students that she became a local celebrity. The Roys lived in the school, and her two children were told to call their mother Mrs. Roy, just like other pupils. In public she was brilliant and demanding; in private, she was mercurial and vicious. Her daughter recalls (in italics): “Get out of my car!” “Get out of my house!” “You’re a millstone around my neck,” and “I should have dumped you in an orphanage.”

As each of them turned nine, Mrs. Roy sent them to a six-year military boarding school. In her daughter’s account, she hated being sent away and the mother never let her children forget her financial sacrifice. She measured “the return on her investment” by her children’s report cards. The girl had excellent grades for which she received a hug. The boy, whose grades were just average, was beaten. “Since then,” the author notes, “all personal achievement comes with a sense of foreboding. On the occasions when I am toasted or applauded, I always feel that someone else, someone quiet, is being beaten in the other room.”

Part of the byzantine mother-daughter dynamic is that the daughter believes that her mother can die at any moment. She imagines herself as an extension of Mrs. Roy’s body, an “organ-child” with an extra pair of lungs that help her mother survive frequent asthma attacks. It will not be until she makes a total break with her at 18 that she begins to feel like a separate human being. The author does not linger over this terrain; she spends more time describing the hills and vegetation of her surroundings.

The daughter’s road out appears when Mrs. Roy’s school outgrows the Rotary Club and she hires an architect to construct a new one. Watching him work, her 14-year-old daughter falls for architecture as well as for the architect’s handsome assistant, whom she dubs JC, a “brown Jesus.” He is a student at the Delhi School for Planning and Architecture, to which she decides to apply. Her mother supports her. “Between her bouts of rage and increasing physical violence, Mrs. Roy told her daughter that if she put her mind to it, she could be anything she wanted to be.” Susanna moves to Delhi, where she drops her first name. Now Arundhati, she writes, “I gradually, deliberately, transformed myself into somebody else.”

Roy’s book is so jam-packed, her language so seductive, her tone so sure, and her pacing so rapid that, on first reading, I didn’t question what seemed exaggerated or was left out. I was uneasy but wasn’t sure why. I wondered why Arundhati didn’t seem curious about how Mrs. Roy became the powerhouse she is: what her childhood was like, where she met the man who became her father, whether she had any friends, whether she was like or unlike other feminist women of her generation. But Arundhati writes so fluently that I didn’t wonder for long. I was racing forward with her to Delhi, where she earns a degree, works at low-paying jobs, lives in a hovel, reunites with and unofficially marries JC, then sails with him to a hippie beach in Goa. It doesn’t work out, and she returns to Delhi after two years, “absolutely alone in the world, with almost no money.” Contacting Mrs. Roy is not, in her mind, an option. Her former thesis adviser finds her a job at the National Institute for Urban Affairs, and she rents a cheap storeroom in a slum adjacent to a cemetery. It overlooks the shrine of a 14th-century Sufi saint — a key site later identified in The Ministry of Utmost Happiness.

“Even then, before the epoch of the Saffron Flag and the Hindu Nation, before Muslims were demonized, ghettoized, and turned into second-class citizens, the dargah was not different from the way it is now,” she writes. “Rats the size of cats with stiff bristly fur made off with food and pilgrims’ smelly shoes. Beggars, some with missing limbs and the most spectacular injuries and illnesses, which they put on display like shopkeepers exhibiting their wares, lined the lanes.”

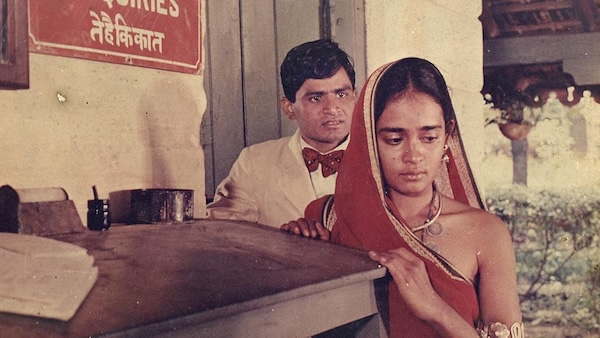

Arundhati Roy in the 1985 film Massey Sahib.

That proximity to India’s impoverished Muslim minority seeds a lifelong commitment to championing their cause but, at the time, she is busy just trying to survive. Smart and beautiful (though she claims ignorance of that), Arundhati writes that she must have had a “cool seraph” watching over her. At work, her boss’s husband drops in, sees her, and instantly decides she should play the female lead in his film Massey Sahib. At 22, she begins a second career — in the movies.

Roy ascribes this unusual succession of events to luck and downplays her “thin, dark and risky” looks. As she archly declares, she entered her new life “motherless, fatherless, brotherless, jobless, homeless. Reckless.” But I noted that a succession of men — classmates, teachers, fellow workers, strangers — helped the “cool seraph” watch over her. Her staging of herself alone against the world, propelled by bravado, reminded me of Italian journalist Oriana Fallacci.

Pradip Krishen — 10 years her elder — is a distinguished academic turned documentary filmmaker. He lives with his wealthy parents, wife, and two children on the second floor of an elegant house in Delhi. He and his wife have an open marriage. He and Roy begin an affair, Roy gets pregnant, has an abortion without anaesthesia, and recovers in Florence, where yet another man — Italian expat friend and sometime lover Carlo — has found her a residency. Every night, she writes to Pradip. “Not love letters,” she clarifies. Really? “I wanted that brilliant man to write back and say, Have you ever considered becoming a writer? That is exactly what he did.”

Until then, in her account, she has had no encouragement to become a writer, no time nor space for writing, as well as no language “in which I could describe my multilingual [Malayalam, English, Hindi] world to myself.” When she returns from Italy, she uses her savings to rent another cheap room — but this time in a posh neighborhood near her lover. She tries to write a children’s book but can’t get it published. She refuses to go back to architectural work. Then “the cool seraph” arranges for Pradip to shoot a film about the repopulation of rhinos in India, for which she writes the script. Then Pradip’s estranged wife dies in her sleep. The flat, ironic narration made me stop to reread and register this as fact, not fiction. Arundhati eventually moves into the apartment the Krishens share on the second floor of his parents’ home. Mrs. Roy even arrives for a peaceful visit.

Arundhati makes her film debut as an actress in Massey Sahib in 1985, then writes screenplays that Pradip directs. One, based on her experiences at architecture school, wins the National Film Award for Best Screenplay. Other projects are less successful and frustrate her desire for creative control. “I longed to work alone,” she writes. “I did not want to confer with producers and actors, not even with my beloved lover-director.” She broke up the professional partnership but, in what she terms a “short-sighted decision,” married Pradip. By then she was deep into reconstructing her early years in an autobiographical novel, The God of Small Things, perhaps the most introspective and interesting part of her memoir.

Once she finishes the book and shows it to her husband, the “cool seraph” steps in again. A literary friend sends the manuscript to another, and within weeks, she chooses an agent who sells the book to 18 foreign publishers for a total of one million dollars in advance royalties. She is 36 years old. The novel mostly pleases Mrs. Roy, who makes a brief appearance, and it will win the 1997 Booker Prize, but, as Arundhati titles the next chapter of Mother Mary Comes to Me, “things fall apart.”

Roy, never comfortable having money, writes that she shares it with family and friends. She also turns to writing nonfiction about social and political injustices, subjects she describes in the latter part of her memoir. Then her mother-in-law dies and, per Indian law, Pradip inherits almost all the family assets, making her even more financially privileged. Arundhati cannot think of herself “as a landlady.” As for Pradip and his children, “I tried not to judge them, the people I most loved, and I failed.” She moves out.

Arundhati Roy speaking at Cambridge in 2017. Photo: Chris Boland

In 1998, India conducted its first clearly military-inspired nuclear tests and Arundhati was among those horrified. “It wasn’t only the possibility of nuclear conflict with Pakistan that worried me. It was what India was doing to itself. I could clearly see where we were headed. We were journeying back to the horrors of Partition, when Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims had turned on one another, slaughtered one another.” She turned from writing novels to nonfiction.

Since then, she has written — often in The Guardian — essays about international as well as Indian issues. After September 11, 2001, she wrote that “The bombing of Afghanistan is not revenge for New York and Washington. It is yet another act of terror against the people of the world.” After the coordinated Islamist terrorist attacks in Mumbai in 2008, Roy wrote that nothing can justify terrorism, but that such violence must be understood in the context of widespread poverty, the Partition of India, and the ongoing Kashmir conflict. She has called for boycotts of Israel and its cultural institutions for at least two decades and wrote most recently, “If we say nothing about Israel’s brazen slaughter of Palestinians, even as it is live-streamed into the most private recesses of our personal lives, we are complicit in it.”

All of her political writing has sparked controversy within and outside of India, not only from politicians but from fellow writers. If the memoir is any guide, Mrs. Roy — who lived to be 89 — rarely spoke out against her daughter’s views and was often vocal in supporting her.

Throughout Mother Mary Comes to Me, I marveled at how much the memoir form could hold, but also wondered how many readers would be willing to stick with it. I learned more about India than about mother-daughter dynamics and found the reading as much work as it was pleasure. When I finished, I wasn’t sure how much I trusted the narrative or the narrator — an unexpectedly ambivalent feeling after the days I spent engaged with Roy’s fascinating story.

Helen Epstein is the author of 12 books of nonfiction including Getting Through It: My Year of Cancer During COVID, and The Long Half-Lives of Love and Trauma. She has been reviewing for The Arts Fuse since its inception.