Film Review: “One Battle After Another” — One Car Chase After Another

By Peter Keough

Director P.T. Anderson’s latest puts up a fight, but it is for a lost cause.

One Battle After Another. Directed by Paul Thomas Anderson. At the Boston Common, Causeway, Kendall Square, Coolidge Corner, West Newton, Somerville, and the suburbs.

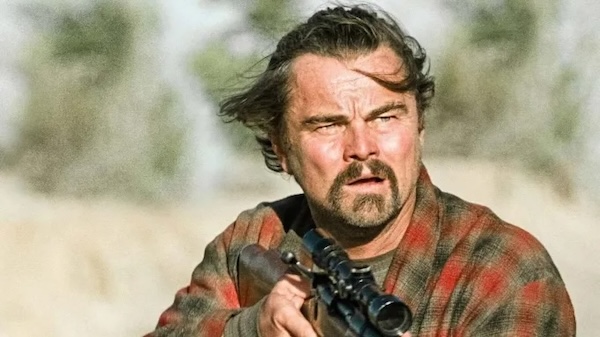

Leonardo DiCaprio in Paul Thomas Anderson’s One Battle After Another. Photo: Warner Bros.

P.T. Anderson’s confused and spectacular One Battle After Another opens like a MAGA wet dream about “Antifa.”

Haughty Black women with names like Junglepussy (Shayna McHayle) rob banks and strut with assault rifles as they terrorize customers and tellers. Buildings that house capitalist enterprises are blown up. An army of guerrillas, called French 75, invade a barbed wire-enclosed immigrant detention center and free those inside. These scenes play like the headlines from the ’60s and ’70s when the Weather Underground and Symbionese Liberation Army were pulling off such actions. But the camps with kids in cages resemble sad scenes from much more recent history. Like Alex Garland in Civil War (Arts Fuse review), Anderson seems to be taking on some of the most divisive issues of our time but only to exploit them.

So when is this happening and in what universe? The Thomas Pynchon novel Vineland on which the film is based had originally been about the travails of ’60s radicals who two decades later are forced to confront their past. But Anderson has decided to awkwardly update the setting to the present day, which would place the guerrilla scenes at the beginning of the film in the mid-’90s, a time when leftist terrorism was virtually nonexistent. That’s just the beginning of Anderson’s problems as, once again, the auteur has, as with Inherent Vice (2014), taken one of Pynchon’s messiest novels and made another mess of it.

But no matter. What is most prominent about the film’s opening is the boner tenting the fatigues of Captain (later Colonel) Steven J. Lockjaw (Sean Penn).

The cause of this indiscretion is Perfidia Beverly Hills (Teyana Taylor). She had gotten the drop on Lockjaw, commandant of the detainee camp, and stolen his hat and gun — and also, apparently, his heart (or some other vital organ). A ruthless Black revolutionary committed to overthrowing the capitalist system and all its evils, Perfidia also becomes, for Lockjaw anyway, a sexual fetish.

Is the attraction reciprocated? It’s hard to say; in the novel, the character (a white woman) has a thing for uniforms. Doltish and deranged and with a bad haircut, the gung-ho martinet, played as a caricature by Penn, is not the most appealing beau. Nonetheless, he tracks down and captures the object of his desire and Perfidia, true to her name, acquiesces to his attentions. She becomes his dominatrix/lover and gives up the names of her fellow fighters for the cause.

That includes her husband Bob “Rocket Man” Ferguson (Leonardo DiCaprio delivers a catchy performance but relies too much on a look of tormented bewilderment), the group’s pyrotechnics and explosives expert. But Perfidia is not the most monogamous type. She breaks free of Lockjaw and returns to Bob, who has gone off the grid. They have a daughter. Who knows? Maybe they could have lived happily ever after had Perfidia not felt the itch and slipped off to resume the struggle for liberation.

The years pass, and Bob has deteriorated into a broken man. The cause he fought for has been defeated, the love of his life has left him, and he is left smoking dope and watching The Battle of Algiers (1966) on TV. His daughter Willa, now 16 (played in a convincing debut performance by Chase Infiniti, though undeveloped by Anderson), is like a second mother to him, a suffocating situation she resents as she wonders about the real mother who deserted her.

Still, it’s a life, until Lockjaw returns and brings an army into Bob’s adopted hometown. Then Willa disappears, and Bob realizes he must recover all his guerilla skills, track down his old contacts, dredge up passwords from the fog of his drug and booze besotted memory, and take up the fight once more.

But this time it’s for his daughter. Before it was just a revolution, now it’s about family, and what follows is an often exciting, occasionally grating (what’s with the endless, atonal percussive soundtrack, Jonny Greenwood?), and gleefully implausible series of Road Runner-like pursuits, captures, car chases, crashes, confrontations, and shoot-outs. One sequence in particular, shot over rolling desert hills, is worthy of Hitchcock. Credit Michael Bauman’s dazzling, redolent, and precise VistaVision cinematography for drawing one into the spectacle, whether it’s of a cathedral-like canyon or the funky details of a living space after decades of dissolute habitation.

What is missing, though, is a consistent tone, point of view, and thematic coherence, a weakness reflected in the unevenly drawn characters. Like Colonel Lockjaw, whose name evokes Kubrick’s farcical inventions of General Jack D. Ripper, Buck Turgidson, and Bat Guano in Doctor Strangelove. But this cartoon figure is far less clever. Moreover, Penn’s cartoonish performance lacks gravitas (he seems to combine General Flynn and Jim Varney). In terms of most of the women and people of color, they seldom aspire to be more than stereotypes or, in the case of Perfidia, are initially presented as an individual with agency and depth but are ultimately reduced to a lampoon.

There are exceptions. Like the Native American bounty hunter Avanti (Eric Schweig), who draws the line at offing kids. Or Sensei Sergio St. Carlos (Benicio Del Toro in a quiet, complex, and compelling performance), who runs an underground railroad for immigrants (they are depicted only as huddled masses shepherded through tunnels and onto buses). Sensei proves Bob’s truest ally and could have been the spiritual center of the film had Anderson done more with him.

As for DiCaprio, he has some moments of genius. In his bathrobe, puffing on various smokables, he is a funkier, less funny version of the Dude from The Big Lebowski (1995). He pulls off one of the funniest bits in the film when he careens from frustration to rage to fecklessness to despair in a series of phone calls with a surviving member of the cabal who insists he remember an inane code. Perhaps a veiled critique of leftist purity tests, it has the zany spirit of the classic “Dave’s not here” skit by Cheech & Chong. However, compared to a towering Anderson creation like Daniel Plainview in There Will Be Blood (2007), who balances absurdity, monstrosity, and pathos, Bob is just a minor character.

What are the film’s values and politics? Ambiguity in this area is usually a plus, but when such volatile issues are at the heart of the story, maybe not. Ostensibly it opposes fascist, racist, inbred patriarchal tyranny as represented by a secret organization that bears the feebly Pynchonesque name of “The Christmas Adventurers Club,” an Illuminati-like group of crapulous, racist, right-wing power brokers and other elites who hang out at a Bohemian Grove type country club.

On the other hand, and it might be incidental, I couldn’t help but notice that the biggest snitches were a Black woman and a nonbinary youth (Bob makes a supposedly comic fuss about their pronouns). And tellingly, by the end, it is suggested that maybe all these battles could have been avoided had Perfidia given up the pursuit of her own life and stayed home and minded the kid.

Peter Keough writes about film and other topics and has contributed to numerous publications. He was the film editor of the Boston Phoenix from 1989 to its demise in 2013 and has edited three books on film, most recently For Kids of All Ages: The National Society of Film Critics on Children’s Movies (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019).

Tagged: "One Battle After Another", "Vineland", Leonardo DiCaprio, Sean Penn, Shayna McHayle

This is the smartest review I’ve read of this film.

What’s the prose equivalent of VistaVision?

Thanks Lisa!

I concur with Lisa, this is definitely one of the better reviews out there that touches on aspects of the movie that most others leave out while offering only lavish praise for the movie. Its score on RT is baffling, the professional critics really went overboard on this. I didn’t care for the movie at all.

One aspect I’d like to see addressed is that the film depicts a non-existent organized & violent left-wing that gives ammunition to the very real & powerful right-wing who imagines just such a dangerous revolutionary multiracial group & which they will use to justify their military installations in urban areas they view as bastions of left-wing danger.

I concur that depicting Black women as hypersexualized has a long, creepy history in American history & media & which only provided the Sean Penn Lockjaw character with a convenient kink with which to be even more dementedly evil.

I agree — gives credence to MAGA’s Antifa fantasies.

One could argue that Anderson does the same thing to the right as well; i.e. the film depicts a non-existent organized & violent right-wing cabal (The Christmas Adventurers Club), that plays into the fantasies of the portion of the left-wing that imagines just such a dangerous conspiracy.

Paranoia is non-partisan.

Thanks

I enjoy your nuanced review on the movie, but I was not a fan of how One Battle After Another portrayed black people. However, I am still glad you were brave enough to intelligently write on the negatives about the movies (unlike other people on Rotten Tomatoes). You should upload your review to Rotten Tomatoes so people get a real perspective of what they will spend their time on.

Thanks Mike. It has been posted on RT (https://www.rottentomatoes.com/critics/peter-keough/movies). I am among the 4% who gave it a rotten tomato.

Pedantic over-analysis of the details for no good reason other than justification of a thumbs-down review. Since when is a movie supposed to be perfectly coherent down to every exact detail. Lighten up and enjoy the ride like other reviews did.

Sorry, Larry, that’s not what critics do.

I applaud your review! So many critics are wildly praising OBAA when it’s not even a top 5 Paul Thomas Anderson film. I’m honestly dumbfounded at the praise it’s getting.

Thanks Jay

Thanks for this, Peter Keough. Your judgment of the film sure sounds right to me.

worth seeing in vistavision though!

Brilliant review, Peter. I remember you fondly from grad school at Circle( whatever it’s called these days), and looked you up. Been perusing your recent work and enjoying your wit and incandescent prose, as well as insightful analyses. Cheers!

thanks Paula!

Peter – thanks for saving me from wasting an evening on a movie I clearly wouldn’t have found worth my time.

glad to help!

I totally agree with your review I also felt that Anderson just took a political setting to tell a rather shallow story. I do not know the book though, so I don’t know how much of the plot is actually from the book. One small comment: Willa is 16 so the guerrilla scenes at the beginning of the movie don’t take place in the 90‘s but rather 2005ish… Doesn’t really make a difference but just in case you would want to correct it…

Interesting point and I looked into what other people have speculated about the timeline and it ranges from 2016 as the present day to 2040 (I’m sure I had solid reasons for pinpointing 1995 but I can’t remember them at the moment) with a lot of people concluding that it takes place in an alternative universe so the date is irrelevant. Apparently it is a major source of discussion about the film. But I find this ambiguity odd for Anderson because most of his best films are firmly set in a well detailed period. So I agree that the actual date doesn’t really matter and that backs up my point that the film exploits political issues for their emotional resonance without making an effort to comprehend them.

Thanks for your comments!

Peter – thanks for an interesting and thoughtful review. It has helped gel some of my own thoughts about what I think Anderson is doing, which I’ve been ruminating about for several weeks. I’ll post a direct response to some of your critiques a bit later, but there are a couple of things you wrote that seem confusing (or incorrect):

“She becomes his dominatrix/lover and gives up the names of her fellow fighters for the cause.”

Both clauses in this sentence are correct, but in-between them, Perfidia has their child, robs a bank, murders a guard, is caught by the police, and pressured by Lockjaw to name names or be imprisoned for 30 or 40 years. I assume you know this, but the combination of those two facts in one sentence makes them seem sequential in time.

“Who knows? Maybe they could have lived happily ever after had Perfidia not felt the itch and slipped off to resume the struggle for liberation.” – (and at the end of the piece) – “And tellingly, by the end, it is suggested that maybe all these battles could have been avoided had Perfidia given up the pursuit of her own life and stayed home and minded the kid.”

But how would Perfidia staying at home have avoided Lockjaw hunting his potential mixed-race child down to eliminate her (and perhaps also Perfidia herself) in order to join CAC?

Good questions. I got the impression that Anderson was implying that Perfidia’a “perfidy” of denying her role as wife and mother and rebelling against the patriarchy is what instigated this particular battle.. That’s my interpretation, that despite the rebellious trappings this is an essentially reactionary film.

“So when is this happening and in what universe?”

After first watching One Battle After Another and noticing many historical references, I spent a fair bit of time trying to decipher exactly what Anderson was doing with the opening 30 minutes (aside from the necessary narrative setup for the second part). A French 75 and a second watch finally shook some pieces into place.

A French 75 is a cocktail named after the French 75mm cannon (because it’s supposed to have a kick like the gun). And the name works on both a story level (the radical group has a kick like the cannon) and a meta level (the radical group is a cocktail). Specifically, the group is a deliberate mixture of characteristics, history and dialogue from the three most notorious US far-left groups in the ’70s: the Black Liberation Army (BLA), the Weather Underground Organization (WUO), and the Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA) – and very likely others that I missed.

As someone with memories of the period, these details jumped out at me:

BLA: the Perfidia Beverly Hills – Assata Olugbala Shakur similarities.

WUO: an allusion to their Haymarket Police Memorial bombing (“We planted a bomb at the Haymarket office of your re-election campaign.”)

WUO: an allusion to their Marin County Courthouse bombing (“Perfidia and I take the courthouse. Bombs are planted.”)

WUO: at least two lines of dialogue, including the title (“From here on in, it’s one battle after another” / “You got an army growing in your fucking guts and you put it there”), lifted from the WUO publication “SDS: New Left Notes” v4 #32:

“FROM HERE ON IT’S ONE BATTLE AFTER ANOTHER — WITH WHITE YOUTH JOINING IN THE FIGHT AND TAKING THE NECESSARY RISKS. PIG AMERIKA BEWARE. THERE’S AN ARMY GROWING IN YOUR GUTS AND IT’S GOING TO BRING YOU DOWN.”

SLA: the bank robbery that went awry with the unplanned murder of someone, with Anderson using a well-known line from the robbery as dialogue (“Get your noses in the carpet”).

SLA: the massive shootout with police that started a fire, killing some group members from smoke inhalation and burns.

…and I suspect there are many other details I didn’t spot.

But the upshot is that the French 75 is basically repeating half-century old history, and the effect is to situate the opening in two temporal periods simultaneously. Narratively (e.g. Willa’s birth, period details, etc) it’s 16 years in a past that is similar to ours (minus the French 75), but symbolically, it’s 50-55 years in our actual past. In this way, PTA can tell a contemporary story while retaining (and updating) what is arguably Pynchon’s main thesis in Vineland, that the violent far-left ’70s groups were a catalyst for a right-wing conservative backlash in the US that led to Ronald Reagan (and continues to this day – with the Democratic Party continually shifting to the new center; i.e. rightwards).

“What are the film’s values and politics?”

I’m not sure I’d want the film to explicitly state its politics to me, but I’d say Anderson’s creation of Sensei Sergio and his underground network (who aren’t in the book) implies where his sympathies lie.

Thanks Mark for your enlightening comments!

You’re welcome Peter. Thank you for your stimulating review!