Book Review: “Matisse at War” — The Makings of a Spy Thriller

By Peter Walsh

All in all, this is a crisp, entertaining, and, so far as I can see, accurate account of the last acts in Henri Matisse’s career.

Matisse at War: Art and Resistance in Nazi Occupied France by Christopher C. Gorham. Penguin Random House, 320 pages, $29

For almost all of Matisse at War: Art and Resistance in Nazi Occupied France, the book’s protagonist is seriously ill, debilitated, bedridden, or, according to his doctors, at death’s door. Henri Matisse, one of Europe’s leading artists, spends most of World War II holed up in the Vichy puppet state, first in a commodious hotel apartment in Nice, then in a villa in nearby Vence. With his longtime wife Amelie estranged and living in occupied Paris, his needs tended to by devoted women who take on multiple roles as nurse, housekeeper, business manager, and model, the painter rarely goes anywhere.

For almost all of Matisse at War: Art and Resistance in Nazi Occupied France, the book’s protagonist is seriously ill, debilitated, bedridden, or, according to his doctors, at death’s door. Henri Matisse, one of Europe’s leading artists, spends most of World War II holed up in the Vichy puppet state, first in a commodious hotel apartment in Nice, then in a villa in nearby Vence. With his longtime wife Amelie estranged and living in occupied Paris, his needs tended to by devoted women who take on multiple roles as nurse, housekeeper, business manager, and model, the painter rarely goes anywhere.

This hardly seems like promising material for an arresting narrative. Yet Christopher C. Gorham’s book reads at times like a spy thriller. That’s partly because it is. Two of Matisse’s children, his son Jean and his daughter Marguerite, are deeply involved in the French Resistance (while his other son, Pierre, runs a gallery in New York, which frequently features the work of European refugee-artists living in American exile). Marguerite and Amelie are betrayed to the Nazis, arrested, and imprisoned; Marguerite is brutally tortured and narrowly, almost accidentally, avoids being sent to a concentration camp. For months, Matisse has no idea where his family members are or whether they are still alive. Vichy Nice is invaded by the Italians, then taken over by the Germans, and later heavily bombed by the Allies. Yet, despite it all, Matisse, as obsessed with work as he ever was, continues laboring mightily against his many disabilities, even managing a breakthrough into his final, revolutionary style with the late, brilliantly-colored, cut-out compositions. All this trial, turmoil, and endurance Gorham describes well, in an easy-to-follow narrative and an informal and engaging writing style.

Matisse at War is not a work of original scholarship and does not present any new discoveries or major insights. It is a popular biography, built up from exhaustive reading in the vast corpus of Matisse scholarship, biography, criticism, contemporary letters and diaries, and memoirs. Gorham rarely expresses an overt opinion of his own, though. Instead, his paragraphs are typically pieced together like a mosaic with multiple direct and usually short quotations from other writers. Although these myriad and disparate fragments, which sometimes overwhelm the narrative voice of the author, can be a bit disorienting to read, the technique is less distracting than it sounds. Gorham’s writing skills help blend everything together into a more-or-less smooth concoction.

Where a scholar would engage with his sources, expanding or amending them to form a synthesis, Gorham mostly just compiles. While his bibliography, notes, and knowledge of Matisse’s works are extensive, he tends to quote a few sources repeatedly, such as the artist and memoirist Françoise Gilot, Picasso’s romantic partner in the later war and early postwar years, and the Matisse biographer Hilary Spurling. In Gorham’s collages of quotations, these sources almost never disagree, either with each other or with his narration. When and if these source accounts diverged, or contradicted his own conclusions, Gorham presumably just omits the evidence.

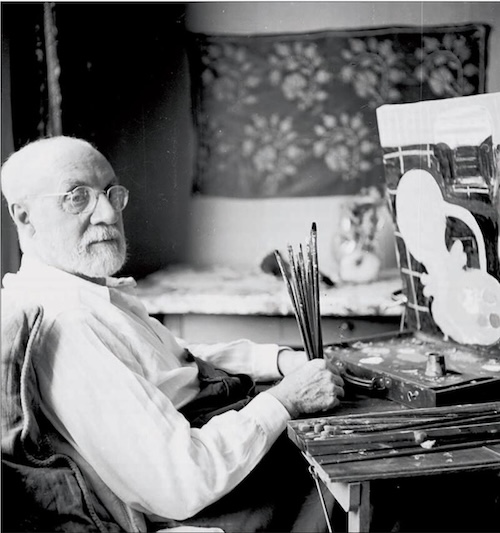

Even in poor health during the Occupation, Henri Matisse was driven to create. Here, he sits in bed at Hôtel Régina in September 1942 with his brushes in hand. © André Ostier, 2025. All rights reserved

Nor does the author follow any of the interesting side paths that might attract a scholar looking to make a splash with new insights. He does not describe in any detail Jean and Marguerite’s work in the Resistance or how it might have impacted Henri’s security. Nor does he speculate about, as others have done, how unapologetically modern artists like Matisse and Picasso managed to survive the cultural suppression of the war years, avoid the vast art confiscations and looting by Nazi officials, and even continue to work, well supplied with artists’ materials during wartime privatizations and restrictions. Did they or their associates make covert arrangements with discreet German admirers in positions of influence? Gorham places the wartime artists in three classes: those who fled France and lived in exile, such as Léger, Masson, and Tanguy; collaborators like Vlaminck and Derain, who even traveled to Germany as visiting artists; and those like Picasso and Matisse, who simply stayed put at home during the occupation. But he doesn’t elaborate on the different experiences these groups might have had during the war, or how they interacted with government officials or other exiles, like Pierre Matisse.

Still, a popular biography of readable length can’t include everything. The book slows a bit near the middle, where much of the text is taken up with Matisse’s poor health, and in the long, postwar epilogue, which has some strange repetitions of chunks of text, a certain level of effusive verbosity, and small errors, likely all the product of hasty editing and the modern practice of typesetting directly from the author’s word processing files.

All in all, though, this is a crisp, entertaining, and, so far as I can see, accurate account of the last acts in Matisse’s career. In the end, by the way, the artist — by then one of the most famous and celebrated on the planet — lived and worked with remarkable productivity well after the war, until the curtain finally came down in Nice in November 1954.

Peter Walsh has worked as a staff member or consultant to such museums as the Harvard Art Museums, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Davis Museum at Wellesley College, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art, and the Boston Athenaeum. He has published in American and European newspapers, journals, and in scholarly anthologies and has lectured at MIT, in New York, Milan, London, Los Angeles, and many other venues. In recent years, he began a career as an actor and has since worked on more than 100 projects, including theater, national television, and award-winning films. He is completing a novel set in the 1960s.