Book Review: “James Baldwin: A Love Story” — An Intimate Biography

By Roberta Silman

We have a biography that reads like a novel in its range and intensity, a biography that forces us to dig deeper into our own preconceived prejudices and understand another man — a famous writer — in ways that neither he nor we might have ever thought possible.

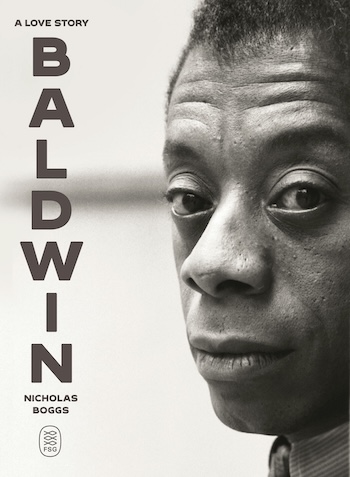

Baldwin: A Love Story by Nicholas Boggs. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 710 pages, $36

This is a remarkable book whose epigraph — “Love is the only reality, the only terror, and the only hope,” from James Baldwin — is the clue to its uniqueness. While there have been earlier, thorough biographies of this profoundly important American writer, this is the first to illuminate Baldwin’s life in such deeply personal and revealing ways.

This is a remarkable book whose epigraph — “Love is the only reality, the only terror, and the only hope,” from James Baldwin — is the clue to its uniqueness. While there have been earlier, thorough biographies of this profoundly important American writer, this is the first to illuminate Baldwin’s life in such deeply personal and revealing ways.

The story of how the book itself came to be is woven into the narrative. As a young gay man, Boggs first read Giovanni’s Room in high school and, like so many of us who encountered it early, was both moved and haunted by it. He soon turned to Baldwin’s essays and came to recognize what made Baldwin’s work so innovative: “Part of what made Baldwin’s work so ground-breaking, I soon realized, was that he did not understand racism as an isolated form of oppression. Instead, . . . he forced readers to confront the connections between white supremacy, masculinity, and sexuality.” Then, in 1996, while a junior at Yale, Boggs stumbled upon Little Man, Little Man, the children’s book Baldwin created with Yoran Cazac about a decade before his death. As Boggs explains:

It began as a quest to bring the forgotten book back into print which thanks to a series of serendipities and the grace and wisdom of the Cazac family and the Baldwin estate ultimately came to pass in 2018. But in the process it also became a search for the truth about Baldwin’s most sustaining intimate relationships and how they shaped his life and art, which has had such an indelible impact on the literary and political landscape of the twentieth century and continues to influence and even offer some measure of hope for the world today. It would not be until close to the end of the voyage that I realized what I had actually been researching and trying to write all along was a new James Baldwin biography. But from the very beginning, I always knew it was a love story.

And so we have a biography that reads like a novel in its range and intensity. A biography that forces us to dig deeper into our own preconceived prejudices and understand another man — a famous writer — in ways that neither he nor we might have ever thought possible.

Baldwin was born in Harlem in 1924 to Emma Berdis Jones and an anonymous father he never knew. When Baldwin was a toddler, Berdis—her preferred name—married David Baldwin, an older man who worked as both a laborer and a preacher, and who brought with him a twelve-year-old son, Samuel. Samuel soon ran away, and over the next sixteen years Berdis and David had eight children together. During this time James took his stepfather’s surname as his own, though their relationship was deeply troubled. David despised white people and strongly disapproved of James’s intellectual pursuits and his white friends—especially the teacher who recognized his talent and exposed him to movies and plays. Toward the end of his life David grew dangerously paranoid. He died in 1943, when James was nineteen and Berdis was pregnant with their last child. From then on, James took on the role of elder brother, charged with helping care for the large and struggling family.

His vision of himself as a paterfamilias was part of his lifelong dream of having a stable family of his own, and after he met the white American economist Mary Painter in Paris when they were both in their twenties, he often fantasized that they would marry and procreate. Because, from early on, he had decided that his writing, especially the stories and novels, depended on his having a conventional, long marriage within which he could love and be loved. Of course, it did not happen; he was Black and bisexual, a man who had sex with women, but clearly preferred men. Although he and Mary eventually went their separate ways, they were close friends until he died, and he dedicated Another Country to her. Yet his deep yearning for such a life, which Boggs grasps so well, is really the key to understanding the profound contradictions in Baldwin’s nature. He always felt deprived, which led to his feelings of alienation, to his need for companionship and sex, to his often dissolute way of life. But his personal dilemma also forced him to think in new ways about his country of birth, his place in it, and the world, and compelled him to write those brilliant essays and early novels which seem more and more relevant with the passage of time.

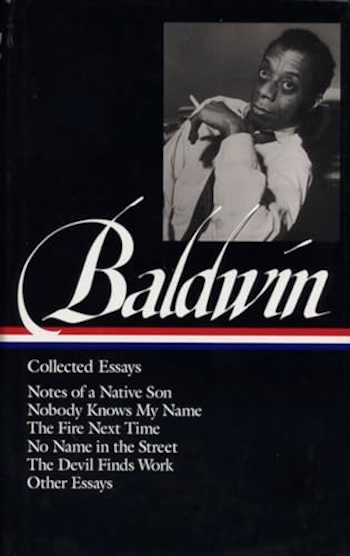

James Baldwin in 1969. Photo: Wikimedia

So it makes sense that this book is divided into parts named for the men Baldwin loved: Beauford Delaney, the Black American painter a generation older than Baldwin, his mentor and father figure, whom he met as a teenager and was close to after Delaney moved to Paris in 1953 and until Delaney’s death in 1979; Lucien Happersberger, the young Swiss man who enabled him to finish Go Tell It on the Mountain, inspired Giovanni’s Room, remained a constant presence in his life, and was at his side when he died; Engin Cezzar, the Turkish actor with whom Baldwin spent long periods in Istanbul, often working as a playwright and director; and Yoran Cazac, the French artist he had first encountered years earlier but with whom he forged a deep bond in the ’70s, who also illustrated Little Man, Little Man. It is striking that the last three were white, married to white women, and fathers—men who embodied the kind of domestic stability Baldwin both envied and found elusive. Beyond them, Baldwin had countless other alliances, some with men whose names are lost, but these four served as ballast: anchors amid a life that was peripatetic and chaotic, marked by both fame and friendship—with figures like Simone Signoret and Yves Montand, Marlon Brando, Katherine Anne Porter, Kay Boyle, Judith Thurman, and so many more—as well as by poverty, despair, and unfulfilled ambitions.

I can still recall with visceral immediacy the impact of Baldwin’s “Letter from a Region in My Mind,” published in The New Yorker in 1963, when I was a young mother. That essay soon became the anchor of The Fire Next Time. Yet it was another piece, a story published two years earlier in The Atlantic—“This Morning, This Evening, So Soon,” about an interracial marriage—that pierced my heart, a story I have returned to many times throughout my life. It encapsulated Baldwin’s anxiety whenever he returned to the United States and, I now realize, also envisioned the very life he had imagined for himself. It also made me understand that if you wrote from the depths of your heart and honed your craft into authentic prose, you had a chance.

And yet, strangely, I had never read a biography of Baldwin until this one. So I had no idea how varied and rich Baldwin’s life was, how widely he traveled, how much time he spent in Europe, and how impossible it was for him to make a home in his native land. What Boggs does so well in this richly detailed book is to weave Baldwin’s private fears and disasters together with his public triumphs and renown. He offers a vivid account of Baldwin’s activism in the civil rights movement, including his devastation at the murder of Medgar Evers in 1963—a moment that scarred Baldwin just as it scarred my husband and me. That was the first of the many assassinations in the 1960s that shaped our lives in so many ways. I was also struck, having recently read David Greenberg’s biography of John Lewis, by Baldwin’s uneasy position in Black political circles, and the degree to which he was sidelined—most starkly at the 1963 March on Washington—because of his sexual identity. I had not known how well-known he became in Turkey, where he spent years at a time directing plays, or how many people, both celebrated and obscure, made pilgrimages to his home in St. Paul de Vence in southern France. There, at last, he put down roots, building the “family” he had always longed for. And where he died, far too soon, in 1987 of esophageal cancer at 63.

In 1973, a young Henry Louis Gates submitted an interview with James Baldwin and Josephine Baker to Time, only to be told that “Baldwin is passé, and Baker a memory of the thirties and forties.” Fifty years later, Baldwin is anything but passé—and the wonder of this fabulous book is that it arrives at exactly the moment we need it most. I will close by recommending it as highly as anyone can. I also leave you with two passages. The first comes from a 1977 interview Baldwin gave to Robert Coles for The New York Times Magazine. When Coles asked about his relationship to his native land, Baldwin replied:

I left America because I had to. It was a personal decision. I wanted to write, and it was the 1940s, and it was no picnic for blacks. I grew up on the streets of Harlem, and I remember President Roosevelt, the liberal, having a lot of trouble with an anti-lynching bill he wanted to get through Congress—never mind the vote, never mind restaurants, never mind schools, never mind a fair employment policy. I had to leave; I needed to be in a place where I could breathe and not feel someone’s hand on my throat.

I left America because I had to. It was a personal decision. I wanted to write, and it was the 1940s, and it was no picnic for blacks. I grew up on the streets of Harlem, and I remember President Roosevelt, the liberal, having a lot of trouble with an anti-lynching bill he wanted to get through Congress—never mind the vote, never mind restaurants, never mind schools, never mind a fair employment policy. I had to leave; I needed to be in a place where I could breathe and not feel someone’s hand on my throat.

The second passage comes from the conclusion of Baldwin’s great 1953 essay, “Stranger in the Village,” in which he reflects on the peculiar relationship between white and Black people, grounded in his experience living in a small Swiss village while he was writing his first novel. He observed that this relationship is unique in the United States because it is inextricably tied to slavery and to the nation’s very founding—a connection unlike that in any other part of the world. Written nearly seventy-five years ago, the essay still speaks with undiminished force. It closes with this prescient paragraph:

The time has come to realize that the interracial drama acted out on the American continent has not only created a new black man, it has created a new white man, too. No road whatever will lead Americans back to the simplicity of this European village where white men have the luxury of looking on me as a stranger. I am not, really, a stranger any longer for any American alive. One of the things that distinguishes Americans from other people is that no other people has ever been so deeply involved in the lives of black men, and vice versa. This fact faced, with all its implications, it can be seen that the history of the American Negro problem is not merely shameful, it is also something of an achievement. For even when the worst has been said, it must also be added that the perpetual challenge posed by this problem was always, somehow, perpetually met. It is precisely this black-white experience which may prove of indispensable value to us in the world we face today. This world is white no longer, and it will never be white again.

Roberta Silman is the author of five novels, two short story collections, and two children’s books. Her second collection of stories, called Heart-work, was just published. Her most recent novels, Secrets and Shadows and Summer Lightning, are available on Amazon in paperback and ebook and as audio books from Alison Larkin Presents. Secrets and Shadows (Arts Fuse review) is in its second printing and was chosen as one of the best Indie Books of 2018 by Kirkus. A recipient of fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts, she has reviewed for The New York Times and Boston Globe, and writes regularly for The Arts Fuse. More about her can be found at robertasilman.com, and she can also be reached at rsilman@verizon.net.