Classical Album Review: Samuel Coleridge-Taylor Orchestral Works

By Jonathan Blumhofer

This fine album demonstrates that the music of neglected, mixed-race English composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor is well worth resurrecting.

“I have long been looking for an English composer of real genius,” the publisher August Jaeger wrote his wife around 1895. “And I believe I have found him.” The figure in question was Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1875-1912), a man who, with the triumph of his Hiawatha trilogy just a few years later, achieved a level of global renown few composers of any era have rivaled.

“I have long been looking for an English composer of real genius,” the publisher August Jaeger wrote his wife around 1895. “And I believe I have found him.” The figure in question was Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1875-1912), a man who, with the triumph of his Hiawatha trilogy just a few years later, achieved a level of global renown few composers of any era have rivaled.

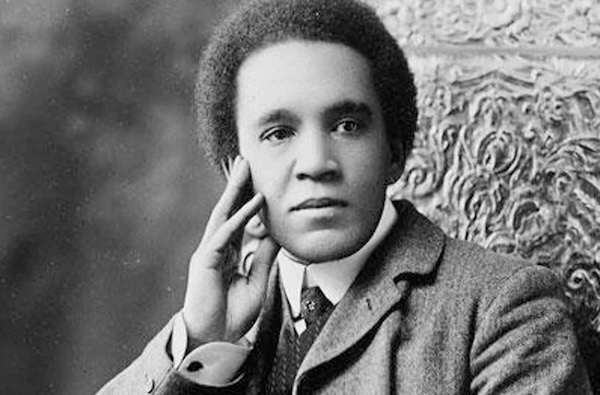

That, today, Coleridge-Taylor isn’t much more than a footnote in music history owes something — though not everything — to his heritage (his father was of Sierra Leonean Creole extraction and his mother was a white Englishwoman). Just as significant was the composer’s sudden death from pneumonia in 1912 and the subsequent revolution in aesthetic taste brought about by The Rite of Spring and the First World War. Like Mendelssohn 70 years earlier, Coleridge-Taylor had the misfortune to die on the wrong side of a major shift in musical values; we can only speculate as to how his career might have developed had he been granted another three or four decades.

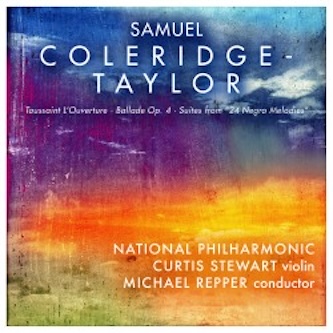

Nevertheless, the body of work Coleridge-Taylor crafted across his 37 short years is significant and a sliver of it forms the focus of a new recording from violinist Curtis Stewart, the National Philharmonic, and conductor Michael Repper. Repper is a longtime champion of this fare, and his familiarity tells in a well-directed account of Toussaint L’Ouverture, Coleridge-Taylor’s concert overture evidently inspired by the Haitian revolutionary.

Granted, the connection between music and title is a bit obscure: certain turns suggest a romance, others a hymn-sing, some more a purposeful march to the Town Green. Yet there’s plenty to admire in the larger work — not least the composer’s wonderful handling of the orchestra and some lovely thematic ideas. Coleridge-Taylor clearly knew his Dvorak and his Liszt, and his writing combines the best qualities of those composers while eschewing their occasional tendencies toward bombast and discursiveness. While the Philharmonic isn’t the most well-blended of recorded orchestras and this music would benefit from a beefier string section, the group captures Toussaint L’Overture’s range of character well.

The collective is also on firm footing in the Ballade in D minor, the work that provoked Jaeger’s enthusiastic response to Coleridge-Taylor in the first place. Cut from the same rhapsodic cloth as shortish contemporaneous concertante numbers by Saint-Saëns, Chausson, and Sarasate, it involves writing of flowing virtuosity and soaring melodicism; the score’s rhythmic swagger periodically seems to anticipate Elgar. Stewart has all its runs and double-stops in hand, though the music would benefit from more warmth and tonal sweetness than it gets on this outing.

The body of work composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor crafted across 37 short years is significant. Photo: Wikimedia

The violinist is completely persuasive, however, in his own arrangements of three movements from Coleridge-Taylor’s seminal 24 Negro Folk Melodies. The original piano versions, which were published in 1905, offer a curious mashup of Black American and African musical source materials heard through the prism of late-19th-century European musical practice.

Stewart’s adaptations of Coleridge-Taylor’s settings of “Deep River,” “They Will Not Lend Me a Child,” and “The Angels Changed My Name” pay respectful tribute to those documents but also take the subsequent 120 years of musical history into account. The results are outstanding: bluesy, soulful, dancing, improvisatory, the set traces a direct line from 19th-century plantation fields to a 21st-century recording studio by way of Jimi Hendrix and Queen. Give it a listen and you’ll hear exactly what I mean.

Perhaps inevitably, Coleridge-Taylor’s own orchestrations of five movements from the Folk Melodies pale a bit in comparison. Some of this is a result of stodgy instrumentation in the outer movements. Also, his version of “They Will Not Lend Me a Child” isn’t particularly compelling, despite affecting writing for solo strings. The intermezzo-like “Don’t Be Weary, Traveler” and noble “Song of Conquest,” however, are profoundly idiomatic and shapely. As in earlier selections, the Philharmonic’s performances are secure if not quite the last word in blend or polish.

Regardless, this album demonstrates both that Jaeger’s verdict was correct and that Coleridge-Taylor’s music is well worth resurrecting. What we now need are mainstream orchestras, ensembles, and leading artists to follow down the trail that Stewart, Repper, and the National Philharmonic have so ably blazed: the composer, the canon, and the audience deserve nothing less.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: Avie, Curtis Stewart, Michael Repper, National Philharmonic