Book Review: Rachel Hadas'”Pastorals” — Everything We Want Poetry To Do

By Jim Kates

Rachel Hadas’s book of prose poems is a set of meditations grounded in a life well lived and much observed, an experimental field for examining the nature of [human] potentialities.

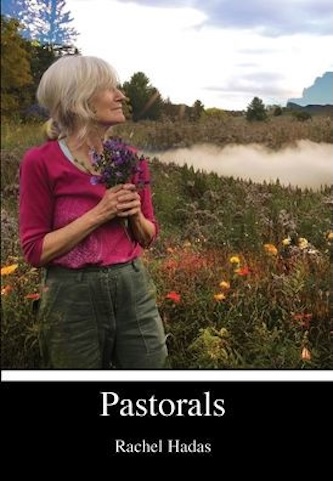

Pastorals by Rachel Hadas. Measure Press, 75 pages, $25

Midway through Pastorals, the poet and Classical scholar Rachel Hadas writes, “I have been struggling to read a book I’d forgotten my father wrote — possibly not his best book, but nevertheless a book I need to read. A book from 1960. He was sixty. Did he know he had six more years to live?”

Midway through Pastorals, the poet and Classical scholar Rachel Hadas writes, “I have been struggling to read a book I’d forgotten my father wrote — possibly not his best book, but nevertheless a book I need to read. A book from 1960. He was sixty. Did he know he had six more years to live?”

In fact, in 1960, the Classical scholar Moses Hadas wrote specifically about the genre his daughter Rachel embraces here: “In the sense that the pastoral poet creates his own world his very artificiality is capable of high seriousness. By disdaining the world of the familiar, fashioning a secluded Arcadia according to his heart’s desire and peopling it with a cast free from the constraints of ordinary convention, the pastoral poet may not only attain the highest reaches of imaginative creativity but also provide himself with something like a rigged experimental field for examining the nature of man’s potentialities.”

Rachel Hadas’s book of prose poems is an earned book, a set of meditations grounded in a life well lived, much observed, and nearer its end than its beginning, a “rigged experimental field for examining the nature of [human] potentialities.” Pastorals is shot through with a consciousness of mortality shaded by the poet’s own knowledge of her Classical antecedents, as well as with an embracing and questioning of her own family — the two activities are inextricably intertwined in this book. If it is an exploration free from the constraints of ordinary convention, that is because the poet’s imagination embraces so very much, without disdaining the world of the familiar. “It’s hard to hear the dead voices,” she writes in one poem. “It’s also a struggle not to listen for them. It was as if nothing seemed to speak, yet everything spoke.”

The poet’s “own world” is one that those of us who live in rural New England recognize easily. Far from being set in a distant Arcadia, this is a deceptively familiar landscape that was depicted and peopled before her by Robert Frost and Donald Hall, among others — a world of apple-picking, flannel nightshirts, spiderwebs, and class 4 roads.

“Don’t forget the phases of the moon. Some nights the moon shines in the window. The hills outside are silver-grey with black shadows. On clear nights when it isn’t overwhelmed by moonlight, the Big Dipper rides above the barn.” (“Windows, Doors”)

Even while I write these lines, outside my window, the hummingbirds zoom back and forth, just the way they do in Hadas’s “Hum of the Season.” The correspondences extend through space and landscape into deep time.

As with Frost and the others, each page is crowded with literary correspondents — from Henry David Thoreau through Thomas Hardy to Elizabeth Bishop — and even when they are not explicitly named:

“The phoebe whose drab color matches the brown and grey of the faded lawn chairs is probably a descendant of the phoebe that built a nest on this same porch one summer late in my father’s life, perhaps even his last summer.”

It is impossible to read this and not hear “Perhaps the self-same song that found a path / Through the sad heart of Ruth, when sick for home …”

What I have always appreciated in Hadas’s poetry is this conversation with other poets, her constant engagement with the time-machine of literature. For her, it is an intensely personal dialogue, the living and dead voices she has lived with her entire life, and the voice she herself has cultivated with care and cunning.

In “Blue Book,” Hadas claims that the waves that do all the work, but it is more than just currents and wind carrying the reader along. There is an artistry that conceals itself in a well-made prose poem — that oxymoron of “a term impossible to define,” as poet/critic Robert Hass has defined it — an artistry honed by a lifetime of immersion in formal verse.

Consider this seemingly simple line from “Dream: The Quest.”

“Dawn. Pale sky. Black boulders line the road. Between suddenly steep banks, a brackish stream is trickling downhill, toward a world underneath this one.”

The alliteration and falling cadences heighten the poetry, propel it on the rhyme of “black” and “brackish” to waters of an Underworld that is not merely geologic, and certainly not theological. It is mythical, Classical, where we meet those who have come before us and with whom we commune. It is also where Rachel Hadas continues to engage with her own people. For all of us, and for all its prose, Pastorals does everything we want poetry to do.

J. Kates is a poet, feature journalist and reviewer, literary translator, and the president and co-director of Zephyr Press, a nonprofit press that focuses on contemporary works in translation from Russia, Eastern Europe, and Asia. His latest book of poetry is Places of Permanent Shade (Accents Publishing) and his newest translation is Sixty Years Selected Poems: 1957-2017, the works of the Russian poet Mikhail Yeryomin.