Book Review: “The Power of Adrienne Rich” — An Aesthetic and Political Force

By David Daniel

Poet Adrienne Rich’s journey serves as a model for meeting the challenge posed for artists and the rest of us today, confronted with the rise of authoritarian forces in America.

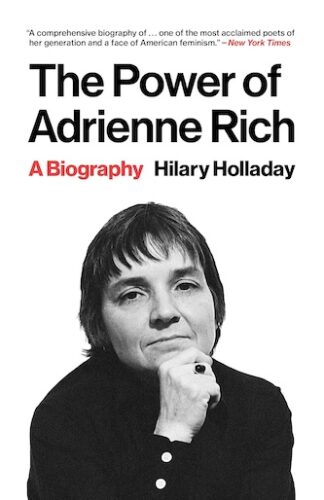

The Power of Adrienne Rich: A Biography by Hilary Holladay. Princeton University Press, 478 pp. Paper. $24.95

In 1950, during her junior year at Radcliffe, Adrienne Rich attended a reading by Robert Frost, then in his mid-70s and comfortably exercising his rustic poet persona. Afterward, in a letter, Rich gushed to her parents that the acclaimed poet “talked so acutely and honestly about poetry that I sat there swelling inside with a great and joyful assent.” That reaction epitomizes Rich’s lifelong, single-minded dedication to the craft of poetry, which was, as Hilary Holladay writes in a preface to her The Power of Adrienne Rich (published in 2020 and newly released in softcover by Princeton University Press), “as close to a religion as anything she would ever know.”

In 1950, during her junior year at Radcliffe, Adrienne Rich attended a reading by Robert Frost, then in his mid-70s and comfortably exercising his rustic poet persona. Afterward, in a letter, Rich gushed to her parents that the acclaimed poet “talked so acutely and honestly about poetry that I sat there swelling inside with a great and joyful assent.” That reaction epitomizes Rich’s lifelong, single-minded dedication to the craft of poetry, which was, as Hilary Holladay writes in a preface to her The Power of Adrienne Rich (published in 2020 and newly released in softcover by Princeton University Press), “as close to a religion as anything she would ever know.”

Born in 1929 in Baltimore, to a southern WASP mother and a Jewish father, Rich was a gifted child. She played Mozart concertos on the piano at age four; at five she practiced handwriting by copying passages from William Blake and John Keats. Her father, a distinguished medical scientist, was a stern taskmaster for his daughter, inculcating in her the belief that hard work was the solution to almost any problem. After some early homeschooling, Rich attended a private school, showing a considerable talent for writing. In her high school yearbook, completing the phrase “wants to be …”, Rich wrote: “remembered.”

At Radcliffe she encountered a heavyweight teaching staff: F.O. Matthiessen, John Ciardi, Archibald MacLeish, and May Sarton. She worked on her poems, which she began to submit to magazines and journals. She got to know fellow students Frank O’Hara, Robert Bly, John Ashbery, and Donald Hall; she had a brief acquaintance with Sylvia Plath, then studying at Smith. This circle of friendships sharpened her commitment to poetry and it would expand over the years to include John Berryman, Hayden Carruth, Robert Creeley, Randall Jarrell, Denise Levertov, Robert Lowell, Tillie Olsen, Richard Wilbur, and others. College also provided the freedom of distance from her family, especially from what she saw as her father’s (and, increasingly, society’s) patriarchal control.

Her first collection of poems was selected by W.H. Auden for the Yale Younger Poets series, and was greeted by good reviews in her final year at college. Upon graduation, and after a year at Oxford on a Guggenheim Fellowship, Rich returned to Cambridge, married a Harvard economist, and became Mrs. Alfred H. Conrad, wife. She continued to work at making a name for herself: in the ensuing years she published volumes of poems and collections of essays; had three children; and taught at various colleges. Her output was steady and garnered admiring attention. In 1970, after a period of estrangement, her husband took his own life. Holladay devotes considerable space and understanding to this tragedy, noting that Conrad’s violent death “transmogrified into a dark gift, for in the absolute failure of her marriage she could no longer pretend she understood how men thought.”

Rich’s sixth collection, Diving into the Wreck, (1973) marked a deepening personal unpacking. A book of “searching, not finding,“ the volume struck a chord with a broad reading public, particularly its long, mythic title poem: “I came to explore the wreck. / The words are purposes. / The words are maps. / I came to see the damage that was done / and the treasures that prevail.” This deep plunge by the poet into her psyche reflected a growing sense of how difficult it was for people to communicate with each other. Along with drawing readers and acclaim, the book also resonated with Rich’s expanding political awareness, symptomatic of the post-’60s reevaluation.

Poet and activist Adrienne Rich. Photo: Dorothy Alexander

Rich took common cause with Shelley, agreeing with his idea that poets serve as the “unacknowledged legislators of the world.” She admits that there is no formula when it comes to balancing the discipline of art with the demand for justice. But Rich asserts that “I do know that art … means nothing if it simply decorates the dinner table of power which holds it hostage.” War protest, feminism, racial justice, and lesbianism: she became a potent voice for these issues, both on the page and at the public podium. The personal was, for her, the political. Channeling the autobiographical impulse through bold acts of imagination turned Rich into a lifelong changeling: of forms, language, and thematic concerns. And these social concerns have not dated. Her 1995 poem, “Deportations” (from Dark Fields of the Republic), could have been written yesterday, with its threatening images of shadowy men snatching people: “Neighbors, vendors, paramedicals / hurried from their porches, their tomato stalls / their auto-mechanic arguments / and children from schoolyards.”

Rich’s journey from a ’50s domestic ideal to becoming a groundbreaking lesbian feminist activist, winner of major literary prizes, was years in the making. Her transformation was shaped by what she made of her own lived experiences, reinforced by her dedicated application of the work ethic her demanding father imbued in her. Her journey serves as a model for meeting the challenge posed for artists and the rest of us today, confronted with the rise of authoritarian forces in America.

It is difficult to convey in an artistic biography the invisible processes that inspire art. The butterfly flit of creativity — an evanescent byproduct in which imagination and the rigorous application of craft meet — is understandably elusive. Holladay analyzes by suggestion, her examinations driven through a scrutiny of the manifold applications of Rich’s “power” (more on this later). The biographer skillfully keeps the life story on track, deftly weaving scads of deep research together with critical assessment: “… a pervasive sense of social inadequacy persisted alongside [Rich’s] abundant self-confidence. Both insider and outsider, she felt important to the world, even essential, yet somehow not fully embraced or loved”; and graceful summary,“The ambitious girl and the nation’s oldest university were well-matched dance partners, each twirling the other with grace and aplomb”). Throughout, Holladay offers keen summaries of Rich’s verse, but she avoids extended explication. Her commentaries do not strive to serve as a substitute for engaging with Rich’s writings directly.

The loops and swirls of a “life” time inevitably pose a sequencing challenge for a biographer. Holladay opts for a straightforward chronology, which makes for a smooth read. Each of the book’s 23 chapters covers a meaningful span of years. Some readers may carp that too much attention (or not enough) is given to Rich’s sexual relationships and personal peccadillos. But really, how germane are these to the growth of Rich’s mind and art? The book’s title initially baffles (how much real power does a poet wield in America?), but it proves to be an ideal choice. The word is repeated (power, powerful, empowering) as it is applied to the multiple strands of Rich’s development as an activist, public intellectual, and acclaimed author. Holladay has written an expansive, fully realized biography of a complex American writer who was as much a force as she was a poet.

David Daniel is a regular Arts Fuse contributor. His essays also appear in the Ideas section of The Boston Globe and elsewhere. His most recent book is Beach Town, a collection of stories.

This is a great review that makes me want to read the book. It sparks, or sparks again, the excitement of discovering Adrienne Rich and her contemporaries in college. And this description is beautiful and perfect, like a butterfly itself: “It is difficult to convey in an artistic biography the invisible processes that inspire art. The butterfly flit of creativity—an evanescent byproduct in which imagination and the rigorous application of craft meet —is understandably elusive.”

Great, insightful review.

Yes, a model of courage and self-realization for us all! As both Insider and Outsider, the status and stance Rich embodied, aesthetically, personally, politically, well highlighted in this incisive review.

Well, she got her wish. She is remembered, well-remembered, in Holladay’s biography and in Daniel’s finely tuned discussion of it.

Dave Daniel does his usual good job of summarizing a difficult book about a difficult subject.

What a great review. For such a short piece, it contains so many richly developed details, among them, Rich’s relationship to her father, her marriage, her friends at Harvard, her precociousness. But the thing I like most about the review is that it got me to look up and read the title poem of “Diving into the Wreck” in its entirety.