Musician Interview: Saxophonist, Composer, and Historian of Early Jazz Allen Lowe — An Invaluable Maverick

By Steve Provizer

“I try to balance self-pity with ambition and anger, and it seems to work, at least from a creative standpoint. That’s the edge — a sense of injustice and resentment, which fuels my refusal to just stop.”

Allen Lowe. Photo: Helen Ward

Allen Lowe is a saxophonist, composer, and historian of early jazz and roots music who doesn’t think he’s getting a fair shake from jazz’s gatekeepers, which include bookers, philanthropies, and arts organizations. He’s a 71-year-old white Jewish man, a musical iconoclast who is not afraid to jump on various third rails. In any era, he might have been an outsider. In the current period of wokeism, DEI, and reparations discussions, it’s no surprise Lowe has become a cultural lightning rod.

Let’s begin by establishing that he talks the talk, but he also walks the walk. He’s associated with a long list of important musicians, and it’s not as if they work with him for the money. A partial list of his collaborators would include Ken Peplowski, Aaron Johnson, Lewis Porter, Anthony Braxton, Doc Cheatham, Randy Sandke, Joe Albany, Don Byron, Matthew Shipp, Julius Hemphill, Marc Ribot, Roswell Rudd, David Murray, Gary Bartz, Nels Cline, Ray Anderson, DJ Logic, Kalaparusha Maurice McIntyre, Michael Gregory Jackson, Ursula Oppens, and Hamiet Bluiett.

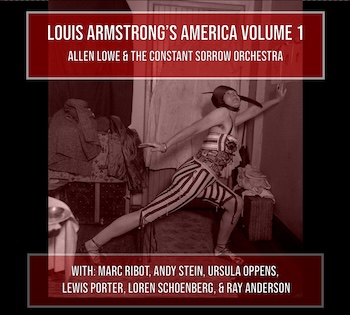

Lowe’s most recent musical project is Louis Armstrong’s America, a two-CD set with 69 tracks, all composed by him. It is one of the most interesting collections of music I’ve heard in a very long time. The music is eclectic in the extreme, touching on many forms — stomps, marches, blues, ballads, jive, boogie-woogie, slow drags, even punk. Lowe says that “it’s work in contemporary forms, but filtered through really old African-American styles; not only African-American styles, but also white hillbilly styles.”

An author, Lowe’s books include:

1996: American Pop – From Minstrel to Mojo on Record 1893-1956.

2000: That Devlin’ Tune: A Jazz History 1900-1950.

2005: Really the Blues? A Horizontal Chronicle of the Vertical Blues, 1893-1959.

2007: God Didn’t Like It: Electric Hillbillies, Singing Preachers, and the Beginning of Rock and Roll, 1950-1970.

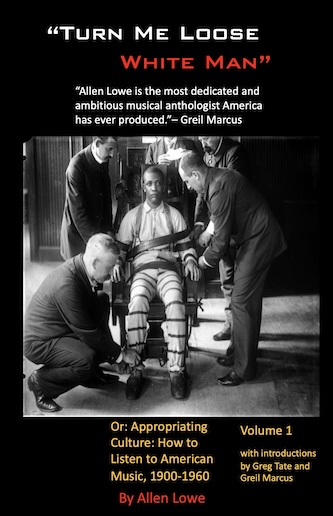

2019: “Turn Me Loose White Man” Or: Appropriating Culture: How to Listen to American Music 1900-1960, a two-volume set of books and a 30-CD set.

Written in clear, nonacademic language, these volumes are deeply researched enough to pass academic muster. In them, Lowe presents an alternative to the standard “great man” narrative of jazz history, arguing for a “bottom-up” approach that listens with fresh ears to each musician’s contribution.

Some of the ideas in Lowe’s writings have been deemed heretical: his undermining of the clichéd link between blues and jazz; the importance of early professional songwriting in creating a repertoire; minstrelsy as a foundational contributor to jazz and other roots music; the current downplaying of the “disreputable origins of jazz,” which Lowe considers to be disrespectful of early musicians, who were proud to play “jazz” and were aware of the social implications of what they played.

Lowe’s biography can be summed up fairly quickly. He grew up in Queens and then Long Island, had a well-traveled college career, eventually getting a degree in Library Science. He was not confident about making a career in music; he didn’t really put himself out there as a saxophonist and composer until he was about 30.

His career received a boost when the late critic Francis Davis named his 1990 CD At the Moment of Impact as a Village Voice pick. That helped him launch an active career in New York City, though he eventually had to move to Portland, Maine, for family reasons. His public musical fortunes plummeted after that, though he continued to write music and books. In 2019 Lowe was diagnosed with cancer: he has been through 20 operations and other treatments. Although not up to full speed, he is currently doing okay.

His career received a boost when the late critic Francis Davis named his 1990 CD At the Moment of Impact as a Village Voice pick. That helped him launch an active career in New York City, though he eventually had to move to Portland, Maine, for family reasons. His public musical fortunes plummeted after that, though he continued to write music and books. In 2019 Lowe was diagnosed with cancer: he has been through 20 operations and other treatments. Although not up to full speed, he is currently doing okay.

In a recent Zoom, Lowe and I discussed some of the subjects that may have thrown his accomplishments into the shadows.

Lowe’s perspective on racial aspects of the music is complex and can seem contradictory. For example, he believes that Black and white musicians are part of a “combined tradition.” He also insists that most American music is African-American in origin. Here a sampling of what he talked to me about:

“As a white musician, I realize that as soon as you begin to absorb the new things that Black musicians have done, they’re on to something new, something different. Hip-hop is very much an offshoot of that. But it doesn’t mean that once it’s absorbed, that white musicians can’t do it. It’s a fact of intellectual and imaginative development that we are, in that sense, on a level playing field, but not on a level playing field economically and racially — clearly.”

“…contemporary America has become so racialized it’s stupid. Where I live, New Haven, arts groups want nothing to do with you if you are a white guy or if you’re not woke enough. Funders want to give money to causes like healing and climate change. I’ve been in this battle against socially linked art. I think it is a big mistake and it produces little good work. At the end of the day, art may have certain political inspirations and origins, but when you produce the work, it’s not social. That moment of creation, of feeling, is aesthetic, and until we understand that, we aren’t going to serve the music well.”

“You put whites in charge of arts organizations and all they see is color. So, they end up advancing musicians who seem to be more socially or image-wise appropriate than musically or artistically accomplished. There are tons of musicians of color who are ignored because they don’t fit the desired image, they don’t play the game… It’s a reverse kind of racism and it’s angered a lot of people. It has angered a lot of white musicians who don’t want to talk about the issue. A lot of white musicians have broken through the racial barriers, but a lot haven’t. I’m stuck in this phantom zone, like in the Superman comics. I am neither in one camp or the other.”

“For example, I don’t get the attention for my projects dealing with the blues because I’m an old white guy. I’m not seen as being authentic enough in this tradition. Most of the major developments in this area have been by Black musicians, there’s no question of that, and it’s not an accidental thing. But my feeling is that blues are no longer folk music, and once that music is out in the world, you can’t prevent people from accessing it and doing the things they want to do with it. You can acknowledge the African-American origin and still understand that these days white musicians can do it as well as Black musicians.”

“People talk about diversity, but all they really want is people who look like themselves. It’s not diversity anymore. I believe that diversity would come from a true alliance between Black and white musicians who understand current social problems, who understand that race is always a factor, but who are also able to work together, professionally, on a level-playing field. Unfortunately, that day, I believe, will never come.”

“People talk about diversity, but all they really want is people who look like themselves. It’s not diversity anymore. I believe that diversity would come from a true alliance between Black and white musicians who understand current social problems, who understand that race is always a factor, but who are also able to work together, professionally, on a level-playing field. Unfortunately, that day, I believe, will never come.”

“Years ago, a study found that imagination and creativity were just as important and valid as experience. My conclusion is that a white person like me could create — after intently listening and experiencing certain forms of Black music — forms that fit authentically within that tradition. I hate to say it, but I think my work has proved that point in the last 10, 15 years. In the Trump years, our nerves have become so raw for political reasons that it’s harder and harder to make that case without seeming like you’re being a reactionary, anti-woke, anti-DEI, things like that.”

“If you’re not famous, they [the jazz business] want you to be young. At the end of the day, people love my music. They don’t care that I’m an old guy with a slightly deformed face with wrinkles and bags under my eyes. We get standing ovations when we play this music.”

Apart from the arts establishment, Lowe aims his most fiery criticism at academic writing, charging that “academic writers almost without exception take a tiny sample and then try to contextualize it as though this sample now illustrates all of this style of music. It’s an abomination. Too many academics do not believe in academic freedom. Several of them have tried to suppress my work. I don’t submit to academic presses anymore. One of the reviews of my manuscripts was vicious. I was called a hobbyist because I don’t have a PhD. I’ve been treated shabbily but, on top of that, they just don’t know what they’re talking about 90 percent of the time.” [Historians Lowe respects: John Szwed, Lewis Porter, and Max Harrison.]

No single voice can speak for jazz and, when someone claims to, I reach to see if my wallet is still there. What’s healthier by far is a civil dialogue among a diversity of voices. And, for his courage in speaking out for his controversial beliefs, Lowe deserves our respect. But, beyond that, the gap between Lowe’s undoubted accomplishments and his lack of payback, needs to be considered. Race, gender, age, and looks have always played a large part in the decisions made by jazz’s gatekeepers. In Lowe’s case, talent seems to have been relegated to an afterthought.

Editor’s Note: Allen Lowe & the Constant Sorrow Orchestra, Louis Armstrong’s America (ESP-Disk) was on the top of the late Francis Davis’s best list of 2024 jazz albums.

Steve Provizer writes on a range of subjects, most often the arts. He is a musician and blogs about jazz here.

Glad to see this. However, I would argue that to the list of “jazz’s gatekeepers, which include bookers, philanthropies, and arts organizations” as people Lowe has gripes with, I would add critics. It’s also worth mentioning that his two-volume Louis Armstrong’s America contains five hours of music. I think I’ve listened to most of it. Which, track by track, was highly enjoyable.

I may not be completely qualified to answer this, but I think his music reviews have been pretty positive, which makes his reception by the rest of the gatekeepers even more egregious.

A wonderful set of albums with such great notes I learned a lot from the music and Allen Lowe’s musical history lessons. I’ve featured it a few times on my Discovering Jazz podcast.