Classical Music Album Reviews: “Somnia” and Eastman & Tchaikovsky Symphonies

By Jonathan Blumhofer

Denis Kozhukin is an inspired guide to music geared toward young players by Sergei Prokofiev and Tchaikovsky; Cleveland Orchestra and Franz Welser-Möst serve up mixed rewards in performances of symphonies by Julius Eastman and Tchaikovsky.

Perhaps it’s unsurprising that music written for children — even music by major composers for children — should fly under the radar. Yet dismissing this catalogue out of hand can be foolish, as anyone who’s heard (or played) Schumann’s Album für die Jugend or Kinderszenen should know.

Perhaps it’s unsurprising that music written for children — even music by major composers for children — should fly under the radar. Yet dismissing this catalogue out of hand can be foolish, as anyone who’s heard (or played) Schumann’s Album für die Jugend or Kinderszenen should know.

Jean-Yves Thibaudet reminded us as much with a recent traversal of excerpts from Aram Khachaturian’s Pictures of Childhood. Now Denis Kozhukin is reinforcing the point, and a bit more thoroughly, with Somnia, a survey of music geared towards young players by Sergei Prokofiev and Tchaikovsky, as well as the Piano Sonata No. 2 by Alexey Shor.

The two big takeaways from the Prokofiev and Tchaikovsky sets: first, they date from each composer’s maturity and second, neither man made major stylistic concessions for their intended audiences. True, Prokofiev’s 1935 Musique d’enfants doesn’t channel the mechanistic spirit of his Symphonies Nos. 2 & 3 or the Scythian Suite. But the work dates from around the same time as Romeo and Juliet, and it sounds like it.

While there’s no obvious cross-pollinating going on between those scores, there’s not much spiritual distance between the latter’s languorous first-act Introduction and the former’s dreamy “Morning” — or, for that matter, Romeo’s “Dance with Mandolins” and Musique’s Mozartian “The Moon Strolls in the Meadow.”

Kozhukin’s has a wonderfully characterful grasp of all of it, getting the crafty little “Waltz” to lilt just so and mining the cheeky swagger of the echt-Prokofievian “March.” He’s just as sensitive to the music’s darker turns, like “The Rain and the Rainbow’s” pungent dissonances and the touchingly phrased, very direct “Regret.”

The Russian pianist is on similarly firm footing in Tchaikovsky’s Children’s Album. Written in 1878 — the same year the composer completed Eugene Onegin and the Violin Concerto — this is a marvelously fresh and varied bouquet of miniatures. Sometimes, as in the opening “Morning Prayer,” its textures and mood recall Schumann. At other times, the music inadvertently looks forward: you get a hint of where Stravinsky was coming from listening to Tchaikovsky’s “Kamarinskaya”—and there’s a direct preview of The Nutcracker in the “Neapolitan Song.”

Throughout, Kozhukin’s an inspired guide. He draws out the whimsical resonance of “The Accordion Player” and the glinting sparkle of the “Lark Song.” A surprising degree of pathos emerges in the short “Old French Song,” while “The Sick Doll” and “The Doll’s Funeral” result in some Gould-ish humming from the keyboard, captured on tape.

The last is, admittedly, a bit distracting. But what goes right here more than compensates.

That includes Kozhukin’s performance of Shor’s Piano Sonata No. 2. This isn’t music that reinvents the wheel, but especially in this context, the three-movement score fits agreeably. Its songful Adagio is framed by two energetic sections that bubble with vitality. In the second of those, some syncopations and slightly bluesy turns add welcome shades of contrast to the larger proceedings.

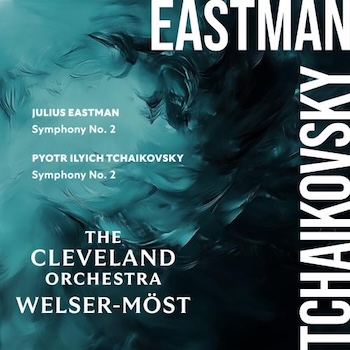

What makes a symphony a symphony? In the case of Julius Eastman’s Second, it seems to be because that’s how the composer styled his score — no more, no less.

What makes a symphony a symphony? In the case of Julius Eastman’s Second, it seems to be because that’s how the composer styled his score — no more, no less.

In many regards, Eastman, who died forgotten in 1990, is not a composer one expects to have explored this genre. Most of his output is experimental and for smaller (and sometimes undefined) ensembles. And, indeed, this work, written in 1983, was lost until the 2010s.

Like most of Eastman’s undertakings, the Symphony reckons unapologetically with the composer’s homosexuality; in this case, the subtitle “The Faithful Friend: The Lover Friend’s Love for the Beloved,” alludes to a specific failed relationship. Accordingly, the music is marked by a brooding, searching quality. In its rhythmic and textural density, and its seeming references to sung melodies (the opening theme vaguely evokes the character of a spiritual), it calls to mind Ives, though its denouement is nihilistic rather than transcendent.

This new recording, from the Cleveland Orchestra and Franz Welser-Möst, brings a refinement to Eastman’s music that one doesn’t always find in it. That’s more than welcome. Playing with trademark warmth and depth of tone, theirs is a solid, focused, well-balanced performance — but one that doesn’t quite put to rest doubts about the effectiveness of the score’s structure, content, or shape.

Tchaikovsky’s own Symphony No. 2, which fills out the album, is better-established in the repertoire, though it’s sometimes dogged by failures of performative nerve. This time around, Welser-Möst and his forces turn in excellent accounts of its first two movements — plush, stately, noble, well-directed — and then completely lose their way over the last two.

Not that the Clevelanders’ playing is at fault: for crisp articulations, rhythmic unanimity, and color, they deliver. Rather, the reading is undercut by inexplicably sluggish tempo choices that sap all the tension, life, and excitement out of the music. The Scherzo plods. So does the finale, which drags whenever it needs to drive. The results are mystifying and frustrating, especially as this can be one of the canon’s truly thrilling scores.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: "Somnia", Cleveland Orchestra, Denis Kozhukin, Franz Welser-Möst, Julius Eastman