Book Review: “Queer Moderns” – Party On, Max!

By Trevor Fairbrother

Max Ewing is little known today, but this book celebrates him as a sexually nonconforming bachelor who strove to impress the quirkiest bohemian clique of the Roaring ’20s.

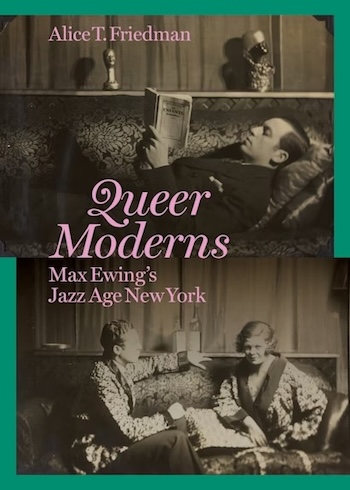

Queer Moderns: Max Ewing’s Jazz Age New York by Alice T. Friedman. Princeton University Press, 280 pages, $49.95

The two 1929 photographs by George Platt Lynes portray Max Ewing and Zena Naylor; they are part of the Max Ewing Papers, Beinecke Library, Yale University

Alice T. Friedman taught modern architecture and design at Wellesley College for 43 years. In Queer Moderns: Max Ewing’s Jazz Age New York, her first book since retiring, she conducts an interdisciplinary study of a young man seeking a name for himself as a pianist, poet, composer, photographer, sculptor, and novelist. Ewing is little-known today, and Friedman celebrates him as a sexually nonconforming bachelor who strove to impress the quirkiest bohemian clique of the Roaring ’20s.

Max Ewing (1903–1934) was the only son of a couple who owned a dry-goods store in rural Ohio. He studied piano from an early age and developed a star-struck penchant for staging at-home entertainments in which he dressed as a vamp. In 1920 he enrolled at the University of Michigan as a student of music, psychology, and literature. Ewing was enthralled by Carl Van Vechten’s first novel, Peter Whiffle: His Life and Works, published in April 1922, and he extolled the writer in his college newspaper. By the end of 1923, he had dropped out, moved to Manhattan, and befriended Van Vechten, whom Friedman describes as a married man “whose queer bisexuality and late-night exploits were legendary.” She says Ewing had “a generous allowance of around $3,000 per year … plus occasional gifts from his parents for special requests.” With New York as his base, he made two extended trips to Europe in 1926 and 1927.

Friedman’s Queer Moderns could not have been written without the Max Ewing archive established at Yale University in 1943. The book pays particular attention to that collection’s assets: letters written frequently to family members and a trove of photographs, including albums and scrapbooks. Ewing’s first objective was to become a concert pianist. Alas, his professional hopes were dashed in 1927 when he permanently injured a finger performing an extremely demanding part in George Antheil’s avant-garde Ballet mécanique. His musical passions were varied: he worshipped Stravinsky and he composed numerous items for Grand Street Follies, a series of musical revues spoofing Broadway’s latest successes.

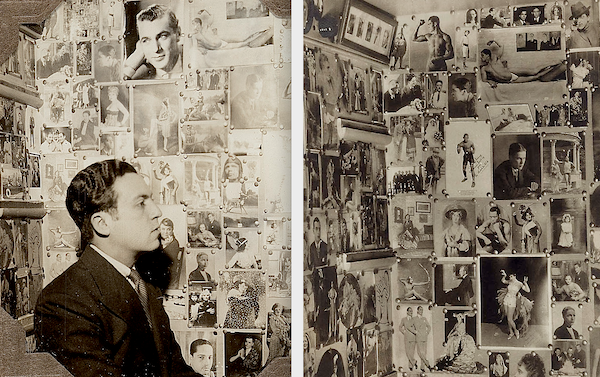

Ewing and his “Extraordinary Portraits” display. Details of two items in the Max Ewing Papers, Beinecke Library, Yale University.

In 1928, soon after moving to a commodious top-floor apartment on West 31st Street, Ewing concocted a madcap social coup with a project he called “The Max Ewing Collection of Extraordinary Portraits.” Over the years he had gathered images of inspiring contemporaries and esteemed forerunners, including: spectacular wild women (Mae West, Josephine Baker, Tallulah Bankhead); homosexual luminaries (Oscar Wilde, Serge Diaghilev, Andre Gide); gorgeous aristos (Lady Diana Manners, The Prince of Wales); macho men (Jack Dempsey, Ernest Hemingway, Kid Chocolate), and lots of singers and pianists (Beatrice Lillie, Geraldine Ferrar, Arthur Rubinstein, Myra Hess). Ewing pinned over 200 of them to the walls of a 4-by-4-foot walk-in closet with a sink on one wall, drolly crediting his inspiration to the flock of paintings of famous people housed in Florence’s Uffizi Gallery. The experience he created was a rebuttal of the racist, homophobic and class divisions that prevailed in the socio-cultural mainstream. Thus, Friedman’s “young man with big dreams and a campy queer manner” assembled a fictive family in a snug private space. A family-funded booklet with an annotated checklist of the collection served as Ewing’s means to tempt friends and acquaintances to visit his whimsical sanctuary.

Ewing turned next to sculpture, beginning with a series of shrine-like tabletop figurines of the imperious and audaciously theatrical interior decorator Muriel Draper. In Muriel Enlightening the World (1930) the subject stands beside a column with a functional lightbulb; she wears a fringed evening gown and holds up an axe; the tchotchkes at her feet include a cat and a miniature Statue of Liberty. Ewing’s idiosyncratic style had affinities with the vibrant, playful, folkloric paintings of his socialite friend Florine Stettheimer. The Muriel sculptures are known today only through photographs in the Yale archive.

Ewing and Jack Pollock posing in front of a poster for the 1932 horror film Freaks. Included in an album in the Max Ewing Papers, Beinecke Library, Yale University.

Friedman shows limited interest in Ewing’s writing. For example, she skirts Sonnets from the Paronomasian, the small book of poetry he published in 1924. In that work, which foreshadowed his “Extraordinary Portraits” installation, Ewing dedicated each of the 26 sonnets to a different person; those he honored included Igor Stravinsky, Geraldine Farrar, Mitja Nikisch, Marguerite d’Alvarez, Aline MacMahon, Eva Gauthier, and Glenway Wescott. Late in December 1932, Alfred A. Knopf launched Ewing’s novel, Going Somewhere. Robert E. Locher’s book jacket showed the cast of characters in an Art Deco style, and featured this quote from Carl Van Vechten: “An amusing, amazing, fantastic, scandalous, good-natured encyclopedia of the gossip of our times.” Friedman tags it as “highly mannered” and “frothy” and offers no synopsis. Perhaps her decision to say so little about the novel was influenced by the review in the New York Times: “[Ewing’s] characters are papier-mâché creations that walk with creaky joints and speak in epigrams faintly reminiscent of Proust and Carl Van Vechten. … Despite the title, [the story] doesn’t get anywhere. … On the whole, Going Somewhere is a dreary, labored transcription of remarks that can be heard any day in certain drawing rooms and studios” (January 8, 1933).

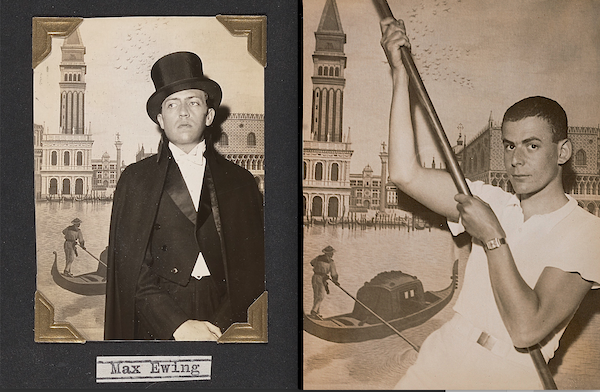

Concurrently, Ewing was actively exploring photography. On January 26th, 1933, the Julien Levy Gallery presented a “one day only” exhibition of 76 pictures titled The Carnival of Venice: Photographs by Max Ewing. He began the undertaking in April 1932 and took all the pictures in his bedroom on West 31st Street. Subjects were invited to pose as they wished in front of a decorative window shade painted with gondolas and a view of Piazza San Marco. Some participants embraced the fantasy: Lincoln Kirstein pretended to be a gondolier, wearing white and wielding a pole, while Paul Robeson posed in costume as Othello. The other subjects included Agnes de Mille, E. E. Cummings, and Isamu Noguchi. Everyone was named in a pamphlet with a text by Gilbert Seldes, the champion of comic strips, vaudeville, and American popular culture. The February issue of Town & Country illustrated four of the Carnival photographs in an article on Ewing and Going Somewhere. The Venetian project was reprised on February 18th when the Waldorf Astoria celebrated Ewing’s double debut as a novelist and artistic photographer with an afternoon tea dance in its Empire Room. General admission was $1.50; two orchestras were on hand; the photographs were hung in a double line on a 40-foot wall. (In a letter to his mother about the upcoming tea dance Ewing noted, “They are going to show all the [Carnival of Venice] pictures I showed at the Levy Gallery except the Negroes, who do not seem to rank at the Waldorf-Astoria!”)

In hindsight, early 1933 was probably the pinnacle of Ewing’s prominence. With a banking panic unfolding and his recently widowed mother fretting and nudging him to move back to Ohio, he decided to quit New York and go west. By September he was in Hollywood, struggling to be a journalist or script writer. Early in 1934 he moved to Ohio to be with his ailing mother. In June, a few weeks after her death, he committed suicide. (Many of Max’s high-strung letters from this period were fully transcribed for the independently published biography, Genius Denied: The Life and Death of Max Ewing by Wallace K. Ewing.)

Ewing and Lincoln Kirstein from the “Carnival of Venice” project. Two items in the Max Ewing Papers, Beinecke Library, Yale University

The person who helped Ewing most in his last years was Jack Pollock, an itinerant boxer and ex-marine who claimed to have been treated badly by his wife. Ewing took a shine to him in 1932 and wrote his mother about hiring a “magnificent athlete” as a trainer. He included a picture of Pollock in the Carnival of Venice exhibitions in 1933. While Friedman constructs a poignant narrative of Pollock’s actions and visits in 1933-34, she is cautious about defining the bond he shared with Ewing. She describes the boxer as a “friend, trainer, and perhaps occasional lover”; notes that evidence of a sexual relationship “is, as usual, inconclusive”; and characterizes the relationship as “flirtatious and undoubtedly erotic, but probably never consummated.”

As an old man, in the 1950s, Van Vechten assembled numerous private scrapbooks. Friedman lingers over them because they include several male nude photographs taken by Ewing. As Jonathan Weinberg observed in The Yale Journal of Criticism, the scrapbooks were “essentially homemade sex books” that were “purposefully vulgar.” On one album page, a full-frontal nude

Friedman stresses the rarity and significance of the Ewing archive: shame has often driven families to destroy “evidence” about queer kith and kin, and pervasive structural homophobia has curtailed institutional record keeping. For her, Van Vechten was an arrogant and controversial figure: she calls attention to his “offensive, failed efforts to portray himself as an expert on African American culture in the 1926 book for which he remains best known.” (The “1926 book” is his fifth novel, Nigger Heaven.) Despite all this, she salutes Van Vechten for persuading Ewing’s relatives to join him in 1943 in donating their letters and papers to establish the archive at Yale.

Friedman took a gamble in choosing to approach the queer social networks of 1920s New York through the eyes of a little-known, lesser talent. The gambit paid off because Ewing’s ambition, the glamorous photographic record ,and his name-dropping letters make for a winning combination. The text becomes repetitive as it keeps tabs on the main players and their sexual jaunts but, overall, Queer Moderns is lively and well written, a sympathetic portrait of a needy dilettante who strove brightly until his tragic emotional crash.

Trevor Fairbrother is a curator and art historian. In 2018, his essay titled “Picture Portraits: Miss Warhol Knows What the Client Wants” was published in the catalogue for the Whitney Museum’s monographic exhibition Andy Warhol – From A to B and Back Again. © Trevor Fairbrother

Tagged: "Queer Moderns: Max Ewing's Jazz Age New York", Alice T. Friedman, Jazz Age, Max Ewing, Princeton University Press, queer