Book Review: Life in a State of Sparkle — The Writings of David Shapiro

By Michael Londra

You Are the You: Writings and Interviews on Poetry, Art, and the New York School by David Shapiro. Edited by Kate Farrell, Foreword by David Lehman. MadHat Press, 332 pp, $23.95

While David Shapiro’s criticism is audacious, his interviews are self-deprecating and offbeat, filled with surprising reveals.

In On the Road, Jack Kerouac proclaimed that “the only people for me are the mad ones.” Nothing wrong with that; but I dig the sane smarties. Scroll YouTube for Charlie Parker interviews, for instance. You will encounter an intellect capable of parsing the most obscure disciplines. It should be no surprise that Bird’s polymath genius produced revolutionary music that spawned generations of copycats. Whether it’s Jimmy Page gushing over surf guitar or Quentin Tarantino motormouthing about grindhouse flicks — listening to superior artists talk about what they love lights up both their brains and ours. It’s not enough for a “creative” to be sui generis. The best of the best are sui generous — communicating the naïve enthusiasm that generates artmaking and its appreciation. Poetry has its fair share of these charismatic omnivores. David Shapiro — poet, professor, critic, art historian — was one.

In On the Road, Jack Kerouac proclaimed that “the only people for me are the mad ones.” Nothing wrong with that; but I dig the sane smarties. Scroll YouTube for Charlie Parker interviews, for instance. You will encounter an intellect capable of parsing the most obscure disciplines. It should be no surprise that Bird’s polymath genius produced revolutionary music that spawned generations of copycats. Whether it’s Jimmy Page gushing over surf guitar or Quentin Tarantino motormouthing about grindhouse flicks — listening to superior artists talk about what they love lights up both their brains and ours. It’s not enough for a “creative” to be sui generis. The best of the best are sui generous — communicating the naïve enthusiasm that generates artmaking and its appreciation. Poetry has its fair share of these charismatic omnivores. David Shapiro — poet, professor, critic, art historian — was one.

His posthumous, newly published collected prose, You Are the You: Writings and Interviews on Poetry, Art, and the New York School, assembles decades of reflections on a diverse range of subjects. Indeed, You Are the You is reminiscent of a career-spanning vinyl box set; there are a ton of grooves to dip into. Wherever you drop the needle, a stimulating thought emerges. And there are plenty of prime tracks. Effusive and uninhibited, Shapiro was never reluctant to express himself. Each of these essays and conversations reveals an eagerness to engage in brash debate. Joanna Fuhrman — who conducted one of the five interviews included here — put it like this: “David Shapiro’s writing is simultaneously earnest and explosive.” The volume showcases this heartfelt seriousness and take-no-prisoners intensity, a fire that burned inside someone who, at first glance, would seem to be anything but passionate, given the bookishly reserved expression that peers out from the Fairfield Porter oil portrait used for the cover.

This ferocity is never more evident than in Shapiro’s analysis of the New York School Poets, who were his mentors. Shapiro engaged these writers with sensitivity and unflinching honesty. Pulling no punches, Shapiro gives each his due without the blurb-crazed overpraise that often comes when one friend reviews another. The piece “Words in a State of Sparkle,” surveys an entire issue of the legendary magazine “C”: A Journal of Poetry. The probe covers a huge amount of aesthetic territory with dispatch, critiquing flaws and highlighting strengths. Shapiro was able to give Kenneth Koch his due praise in this essay, while silencing the poet’s haters with a 10-word mic drop emblematic of Shapiro’s trademark reviewing style. He wrote this line, according to Farrell’s footnotes, at age 17: “[Koch’s] humor has steel wires in it, as does Mozart’s.”

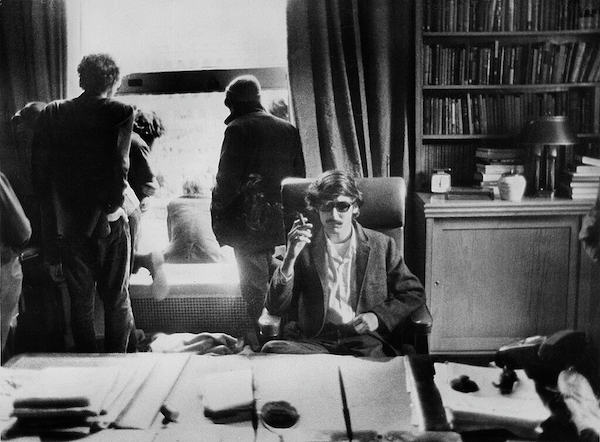

Shapiro was, in fact, a prodigy. Admitted to Columbia University as a 16-year-old, he tasted notoriety after a snapshot of him appeared in a 1968 Life spread on Vietnam War protestors. He broke into Low Library with fellow student activists and the picture was taken after he had commandeered the leather desk chair of Columbia University’s president, Grayson Kirk. Wearing dark sunglasses and wielding a cigar, Farrell notes that the photograph “came to represent …‘the era’s revolutionary zeal.’” This iconic black-and-white image (included in You Are the You) shadowed Shapiro throughout his life. It was appended to his New York Times obituary; he died from complications of Parkinson’s disease in 2024. Reminiscent of photos of Miles Davis and Patti Smith as they swaggered in their rebellious pomp, Shapiro’s rock star pose strikes the viewer like a challenge, proclaiming poetry to be the new sheriff in town. What are you gonna do about it?

Shapiro’s bravado is what gives his criticism its bite, particularly in the essay “Urgent Masks: An Introduction to John Ashbery’s Poetry.” Here he appraises a 20th-century poet that many critics have found difficult to elucidate. The customary strategy is to lean on perfunctory mentions of surrealism, along with tacked-on tributes to Ashbery’s use of colloquial speech. “Urgent Masks” might be the strongest attempt yet to come to grips with Ashbery’s elusive sonic effects, simply because Shapiro is adept at approaching material from slant angles. Other adventurous trips include looking at cultural theorist Walter Benjamin as a poet, along with original reflections on James Schuyler, Elizabeth Bishop, Donald Hall, Edwin Denby, Denise Levertov, Anne Porter, Ron Padgett, and Frank Lima. Shapiro was also interested in visual art; there are inventive considerations of painters Cy Twombly and Jasper Johns.

Student activist David Shapiro sitting behind University President Kirk’s desk smoking an appropriated cigar during a six-day campus uprising and protest at Columbia University, New York in May, 1968. Photo: The LIFE Magazine Collection, 2005

While Shapiro’s criticism is audacious, his interviews are self-deprecating and offbeat, filled with surprising reveals. For the New York Quarterly, Shapiro advocates dissent as the best guide to aesthetics: “I believe in uncontrollable beauty, and I believe in the subversive aspects of beauty.” Gesturing to his flamboyant literary style, he concedes, “Some people seem to think I have a Catherine Deneuve complex.” His greatest influence, interestingly, turns out to be “being born a violinist,” an eye-opener that emphasizes that, for him, the links between poetry and music aren’t just lip service — the relationship is symbiotic, not symbolic. On that point, however, Shapiro at times strains too hard for musical sublimity. For example, at times his valuable essay on Wallace Stevens shoots into the incomprehensible: “The ‘the the’ is objet trouvé and the given of language.”

One strong candidate for the central text in You Are the You is “Van Gogh, Heidegger, Schapiro, Derrida: The Truth in Criticism,” an essay that whirls its ideas. At its heart, this is a scholarly, yet accessible, examination of Van Gogh’s painting Old Shoes. Leaping with verve into a notorious three-way dust-up on the picture among art scholar Meyer Schapiro, Derrida, and Heidegger, Shapiro educates and entertains, holding the trio’s feet to his fire: “What Heidegger and Derrida forget is this sense of the bohemian in Van Gogh, especially in the Paris period, but also before. Van Gogh, like Rimbaud, is observant and self-observant.…[s]ome theories may not foreground the human, but it is an inescapable part of art.”

Concluding the volume is the eponymous poem “You Are the You,” which also serves as Shapiro’s farewell to his readers — we are all the “you.” You Are the You is an eclectic anthology filled with the passions that animated Shapiro across 50 years, enthusiasms that he wanted to spread to us all. In this final lyric, Shapiro offers the consolation that everything will pass. Faith in the world is tenuous; or as he puts it, “boats break.” Hearts also “break.” Death gets the last word. But poems — and the love that shapes them — will endure:

To look up into your face

Is like looking into the devastated stars

Lights of all kinds I traced,

You and you and you and you.

You are the you of this poem, mon amour.

Boats break.

Michael Londra’s fiction, poetry, and reviews have appeared or soon will in Restless Messengers, Asian Review of Books, The Fortnightly Review, The Blue Mountain Review, spoKe, and Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, among others. He contributed the introduction six essays to New Studies in Delmore Schwartz, due next year from MadHat Press, and authored the forthcoming Delmore&Lou: A Novel of Delmore Schwartz and Lou Reed. He lives in Manhattan.

He was my brilliant, younger brother. This was a beautiful testament to his brilliance. There are so many experiences unwritten about him that reveal who he was- not enough, can ever be said about him.