Arts Commentary: From the Editor’s Desk — By Popular Demand, 2025

Back in February of 2024 I began to write a weekly column for the newsletter on Substack. A few readers have asked that I post these opinion pieces in the magazine.

Here is a selection of last’s year’s standouts: Favorite Columns of 2024

Below is a selection of my top picks of 2025.

—Bill Marx, Editor-in-Chief

December 17, 2025

Nadya Tolokonnikova, POLICE STATE, 2025. Performance documentation from The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA. Photo: Yulia Shur. Courtesy of the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA).

On December 15, the Ministry of Justice, sitting in Moscow’s Tverskoy Court, officially classified the art collective Pussy Riot as an extremist organization. This verdict follows a string of individual charges filed against members of the feminist group. Founder Nadya Tolokonnikova was added to the wanted list and arrested in absentia in November 2023. Peter Verzilov was sentenced in absentia in April 2024. Five members — including Maria Alyokhina, Taso Pletner, Olga Borisova, Diana Burkot, and Alina Petrova — were handed down sentences in absentia in September 2025.

Conceptual performance artist and activist Tolokonnikova created the art installation Putin’s Ashes in January 2023, which triggered a criminal case against her, landing her on Russia’s most wanted list. Her latest piece is POLICE STATE, a durational performance installation that premiered at the Geffen Contemporary at MOCA in Los Angeles, from June 5–14. It later moved to the MCA (Chicago) where the run ended on November 30. As of now, I can’t find any confirmed future exhibitions or tour dates for POLICE STATE.

It would be wonderful if a Boston institution stepped in to bring the work here. I am not holding my breath.

A book documenting the installation features photographs, prison letters, etchings, and artwork by fellow Russian political prisoners, along with documentation of the “ICE” and “No Kings Day” protests held outside the museum during Tolokonnikova’s exhibit, all woven into a narrative of resistance. The artist says that POLICE STATE explores the “paradox of confinement and liberation; it both confronts the brutality of control and insists on the possibility of catharsis and connection.” You can order the volume here.

December 10, 2025

I have been looking around for American novels from the 1930s that address the rise of authoritarianism or fascist leanings in the homeland during the Great Depression. The favorite among commentators is Sinclair Lewis’s 1935 novel It Can’t Happen Here, which of late has inspired several stage adaptations and readings. This solid, earnest narrative, which chronicles the rise of demagogues from the top down, lacks Lewis’s customary caustic tang.

A more provocative, visceral work of political satire, which views the polarizing attractions of White Christian nationalism from the point of view of the underclass, has been neglected: Nathaniel West’s A Cool Million. Published in 1934, the novel is rated far below his masterpiece, 1933’s Miss Lonelyhearts, and is deemed inferior to 1939’s The Day of the Locust, still one of the best fictional assaults on Hollywood. I don’t disagree with that assessment, but A Cool Million’s brutal comic vision of American violence and hatred run amok, cartoonish as it is, conveys a rage at dehumanization that speaks to the viciousness of what we are experiencing today.

The episodic storyline follows the dismantling of its protagonist, Lemuel Pitkin. This sad sack of an optimist from Vermont is methodically dismembered during a series of swindles that are symptomatic of the virulent forces — economic and xenophobic — polarizing a country through which armies of the homeless and unemployed roam. Over the course of the book, Pitkin loses his teeth, an eye, a thumb, his scalp, and finally a leg, his condition ultimately landing him a job as the butt of jokes in a vaudeville act, where he is eventually assassinated — a martyr to the autocratic cause espoused by his would-be despot guru, Nathan “Shagpoke” Whipple, ex-president of the United States, head of the Rat River National Bank, and leader of the National Revolutionary Party, which warns its followers that “your sweethearts and wives will become the common property of foreigners to maul and mouth at their leisure. Your shops will be torn from you and you will be driven from your farms.”

In 1993, dramatist James Lapine adapted West’s book for the stage, titling it Luck, Pluck & Virtue. A 2024 theater version of A Cool Million premiered at London’s Brockley Jack Studio Theatre. Enterprising stage companies — take note.

Note: Critic Leslie Fiedler in his 1963 collection No! In Thunder: “West’s bleakest novel is his funnest, A Cool Million, whose title comes from the “Old Saying”: “John D. Rockefeller would give a cool million to have a stomach like yours.”

December 3, 2025

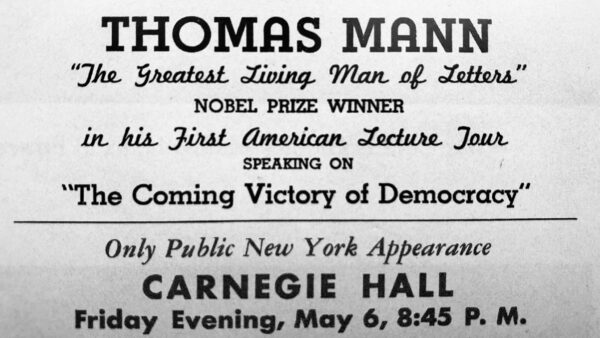

On Dec 1, Brandeis University’s Center for German and European Studies presented a conversation on Thomas Mann’s Antifascist Radio Addresses, 1940–1945 by the editors of the recently published book. You can listen to it here. The excoriating addresses that Thomas Mann broadcast to Germany are fascinating. (Hitler even listened and responded.) What was particularly interesting to me was how prescient the writer was early on, before the world knew just where fascism was headed. In the early 1930s, after he had fled Germany, Mann gave a series of talks in America denouncing the Nazis and the bloody authoritarianism to come. In a 1934 Time Magazine article, Mann said, “As a German, I can understand what has happened and why it has happened. As a human being I cannot justify it. . . . The German people may have learned what it means to be hated; that should only have taught them that vicious hate has no place in the civilized world. … If to be more German means to be less human, I can make only one choice.”

Which of our major artists and writers are touring the country, warning about the ongoing threat that MAGA and the Trump administration pose to democracy? Isn’t there only one choice to make, ‘if to be more American means to be less human’?

November 26, 2025

F. O. Matthiessen with Pansy Littlefield, painted by Russell Cheney, 1926. Photo: russellcheney.com.

This year marks the 70th anniversary of poet and fiction writer May Sarton’s novel excoriating red-baiting and cowardice at Harvard University, Faithful Are the Wounds, which was a finalist for the National Book Award. Mainly set in and around Harvard, Sarton drew inspiration from the suicide of celebrated American literary critic and scholar F. O. Matthiessen—a Socialist, Christian, and closeted homosexual—who died at the age of 48. In his suicide note, Matthiessen wrote, “I am depressed over world conditions. I am a Christian and a Socialist. I am against any order which interferes with that objective.” He had been a target of McCarthyist surveillance of left-wing university academics, accused of being part of so-called “Communist front groups.”

Sarton ignores Matthiessen’s homosexuality, portraying her narrative’s protagonist, Harvard literature professor Edward Cavan, as a monastic figure. She emphasizes his “sheer passionate intensity,” his awkward craving for intimacy and communion. She is much harder on Cavan’s liberal friends and careerist colleagues, who wall themselves off from each other and the demands of the times. What was at stake? One character sums it up in an appearance before a “Washington committee sent down to look into communism at Harvard University.” It is the belief that “the intellectual must stand on the frontier of the freedom of thought, especially in such times as these when this frontier is being narrowed down every day.”

Sarton had this to say about the book in a 1983 Paris Review interview: “I wrote the novel partly because I was very angry at the way people I knew at Harvard reacted after his suicide. At first, as always happens with a suicide, people close to him thought, ‘What could we have done?’ There was guilt. Then very soon I heard, ‘Poor Mattie, he couldn’t take it.’ That was what enraged me, because these people didn’t care that much, were not involved. And Mattie did care. I’m sure the suicide was personal as well as political, and perhaps everything was all wound up together at that point… but he was right in the deepest sense… His belief that people could work together, and that the Left must join, not divide, was correct. It proved to be unrealistic. But he wasn’t nearly as wrong as the people who didn’t care. That’s what I wrote the novel out of.”

It is this response of healthy outrage that makes Faithful Are the Wounds a particularly provocative read today. The story also suggests that the beleaguered F. O. Matthiessen is a critic well worth reevaluating, especially given that 62% of American adults under age 30 hold a favorable view of Socialism. It is this response of healthy outrage that makes Faithful Are the Wounds a particularly provocative read today. The story also suggests that the beleaguered F. O. Matthiessen is a critic well worth reevaluating, especially given that 62% of American adults under age 30 hold a favorable view of Socialism.

November 12, 2025

Last Thursday, I received an Arts|Learning Distinguished Advocacy Award for Media Support of Arts Education at an inspiring ceremony held at the Boston Renaissance Charter Public School in Hyde Park. Critics usually hand prizes to artists – I was honored that this magazine’s nearly two decades of commitment to thinking deeply, seriously, and critically about the arts were recognized by creatives and their supporters.

At that event, I heard about an attempt to advance legislation that should be of deep concern to all who love the arts and worry about their future. Earlier this year, The Lowell Mason Arts Education Equity Act was submitted to the Massachusetts State House. If passed, the bill would mandate a 1% increase in Chapter 70 state funding for all school districts across the Commonwealth. These funds could be used solely for arts education, supplying—within the first year alone—millions in dedicated support, largely for new staffing and programs in the arts. Every student in Massachusetts public schools would have access to high-quality arts education across the creative spectrum (dance, music, theater, visual arts, and media arts).

Jonathan Rappaport, Executive Director Emeritus of Arts|Learning, told me that passing this bill is crucial “because we go through cycles when there are terrible budget cuts and you can guess what is cut first — the arts. And those cuts can be devastating. School districts will go through periods in which the arts will thrive. Then come the cuts; it takes six to ten years to revive an arts program in a district because you have to build it from the ground up, develop a feeder program through the elementary grades up through middle and high school. One of the virtues of this legislation is that it does not ask for towns to provide any additional funding for arts education. It would not take anything away from existing programs — you’re not robbing Peter to pay Paul.”

What’s not to like? Inexplicably, there has been little media/arts industry buzz about this effort to bolster arts education at a time when the arts are under direct political attack. Rappaport says that volunteers have tried to get the word out, but their efforts have been limited. Our artistic institutions and organizations are, as usual, AWOL when it comes to living up to their rhetoric about caring for the community. Hell, what about thinking about their future? Do they have a death wish? The fact is, the students in these invigorated arts education programs across the state will be the artists and audiences of tomorrow. Marketing is not going to be enough to sustain interest: it is essential to nurture a knowledge and love of the arts among the young.

The bill was reviewed at a hearing by the MA legislature’s Joint Committee for Education on September 16. They have until November 15th to decide on the fate of this bill going forward. Through this app you can ask for your local state Representative and state Senator to co-sponsor the bill. Rappaport believes there are plans to make big changes to Chapter 70 funding in general, so he is uncertain about what will happen. The committee may decide to kick the arts education can down the road. Still, for him, “it’s very important we get as many people contacting legislators to support the act because then a lot of legislators will know that this is important to people out and around the state.”

November 5, 2025

At the moment, hate is everywhere in dementedly polarized America, each side of the political spectrum fiercely reviling the other. And that is a bad thing, is it not? There is a knee-jerk consensus that the emotion is self-defeating, its weakness summed up by Confucius’s adage “If you hate a person then you are defeated by them.” But is that always true? German journalist Şeyda Kurt, in her stimulatingly acidic polemic Hate: The Uses of a Powerful Emotion (translated by Jackie de Pont), argues that rage can also nurture resistance, over the long haul, against the racist, patriarchal capitalism we live under. Hate has been, and can be, “a driving force for a collective pursuit of change.”

If nothing else, Kurt supplies a welcome kick in the teeth to our Pavlovian army of itching to sing “Kumbaya” at the drop of an empathetic tear.

Like all disruptive critics, Kurt takes aim at a bromide that many hold sacred: in our civilized Western society, grounded in Judeo-Christian values, hate should be reviled. It is an ugly and destructive emotion. But, for her, this wholesale rejection of loathing only reinforces our indifference to social injustice — it feeds an emotional placidity, a consumer-obedient passivity that accepts the status quo. In response, Kurt calls for the cooperative cultivation of simmering rage — fueled by fixation and stamina — aimed at the proper targets. She calls this a strategic hatred: “A hate that is tactical, considered and circumspect. A hate that radically and completely challenges the prevailing dynamics of violence and domination.”

Hate, a best-seller in Europe, makes for a refreshingly spiky read. Like any radical gadfly, Kurt veers off course from time to time. It would have been helpful to have a few examples of how hate helped spur sustained political movements, not just long-term protests. But, as the current administration slides into authoritarianism (even the NYTimes admits it now) and embraces fascism, Kurt gives our accumulating bands of dissenters blissful, fiery permission to hate fully and freely — though strategically.

October 29, 2025

The controversial baby-stoning scene in Edward Bond’s Saved. Sunday Times theater critic J.W. Lambert : “Was there ever a psychopathic exercise so lovingly dwelt on as this, spun out with such apparent relish and refinement of detail?”

Aside from slowly proceeding court cases, America’s theaters are suffering through the Trump administration’s crackdown on artistic freedom (and federal funding) in abject silence, at least from what I can tell. National efforts, such as “Fall of Freedom,” are coordinating public demonstrations, enlisting prominent artists and cultural organizations to protest the administration’s attempts to control museum and arts programming. An action is scheduled for November 21 and 22. (Castle of our Skins is the only Boston participant listed at the moment.) In terms of programming, however, escapism is being marketed as “bold” fare as usual. Trot out the dysfunctional family dramas and comic book musicals. The fragility of democracy is too risky a topic.

Those concerned about the future of self-censorship in America must look elsewhere. The Stage reports that respected Swiss director Milo Rau’s production for this year’s Belgrade International Theatre Festival was blocked by the event’s board. Why? Could it be political revenge for “Rau’s speech at the festival in 2024, which mentioned environmentally harmful mining practices in Serbia and beyond”? Or might it be the show’s violent subject matter: “The Pelicot Trial is based on the high-profile case of Gisèle Pelicot, who was raped and assaulted by dozens of men.” Whatever the reason, the threat to free expression is real, and growing. “It is very concerning to see how quickly limits on freedom of expression are being normalised around Europe,” said Heidi Wiley, executive director of the European Theatre Convention. “Public theatres and festivals are places of open, critical and inspiring debate, where artists from around the world are able to shine a light on the complex realities of today’s world through their performances and creative interventions.”

Apparently, our cultural-industrial complex intends to ignore the menace posed to “open, critical, and free” discourse on our stages. Perhaps our showbiz machinery thinks we won’t notice. But repression of the imagination must be faced and defeated. 60 years ago, on November 3, the world premiere production of Edward Bond’s Saved by Britain’s Royal Court Theatre stood up to State censorship as well as the braying for blood of a cadre of deeply hostile critics, who condemned the script for what they perceived as its gratuitous violence, particularly a scene in which a baby in a pram is stoned to death. The Royal Court responded to the uproar by hosting a discussion in which Bond and director William Gaskill debated with critics of the play, divided between the sympathetic (Kenneth Tynan and Mary McCarthy) and the dismissive (J. W. Lambert and Irving Wardle).

The upshot of this aggressive defense of artistic freedom: the eventual shutdown, three years later, of the Lord Chamberlain’s Office, which in 1737 had been made responsible for granting licenses to theaters and approving the texts of plays. This outcome is proof that — rather than kowtow to the fear generated by an abusive power — our theaters would better protect themselves by confronting, via productions and public discussions, the perfidy of censorship.

October 22, 2025

One would think that somebody would write on one of the 20th century’s most bilious satires condemning man’s yearning for immortality, given the publicized yearnings of uber-rich libertarians, PayPal founder Peter Thiel among them, who are reported to be fascinated by the ideas of the death-evading “transhumanist” movement, with its interest in “heterochronic parabiosis” — the sewing together of two animals in order to create a living chimera. Aldous Huxley is best known for his 1931 novel Brave New World but, after the first of many stints in Hollywood writing screenplays for MGM, in 1939 he published After Many a Summer Dies the Swan, a book critics consider to be his last major work of fiction. Set on the West Coast, this grotesque fable about American delusions is set in a kitschy, Hollywood-crazed wonderland, a huge estate whose grounds include an ornate castle, a children’s hospital, and a mortuary that no doubt served as one of the inspirations for Whispering Glade in Evelyn Waugh’s The Loved One.

Fascism is on the march in Spain, the effects of the Depression are still being felt, but the aging mega-millionaire, Jo Stoyte, is obsessed with longevity, if only to continue to serve his starlet mistress, Virginia Maunciple. To that end, he has hired the gleefully nihilistic scientist Sigmund Obispo to conduct extensive research into how life can be prolonged indefinitely. It turns out that carp guts may be the key to attaining eternal life, though what happens to the human body after kicking around for hundreds of years is highlighted in the hideously hilarious ending. Also tossed into the mix are a couple of scholars, a smug British historian and William Propter, a former university professor who serves as the loquacious spokesman for Huxley’s vision of a pragmatic Buddhism that insists that we must reject the world as it is for the sake of saving it. Doing good — at the very least limiting harm — means rising above the rapacity of the ego, above the divisions of conventional religion and nationalism.

The plot of this acidic farce is minimal; its characters are either thinking about (or voicing) their obsessions, many of which are interestingly pertinent now. Propter is tinkering with solar power and working on schemes to help the lower class. Stoyte’s urge to overcome mortality smacks of the dreams of today’s biotech entrepreneurs and biohackers (a species anticipated here by the amoral Obispo as well as Stoyte), who see it as their individual right to enjoy life indefinitely, to never stop satisfying their desires regardless of the consequences to morality or society. Huxley admired the iconoclastic H. L. Mencken, and in this outlandish fable joins him in zestfully lambasting American monsters: “the solemn mammoths of stupidity, mountain-bodied and mouse-brained … sinister, rapacious, philanthropic beasts.”

October 15, 2025

Jesse Hinson, Omar Robinson, and Dennis Trainor Jr. in the Actors’ Shakespeare Project’s production of Macbeth. Photo: Benjamin Rose Photography

I have not seen the Actors’ Shakespeare Project’s production of Macbeth, but twee notions about political theater in Don Aucoin’s Boston Globe review left me shaking my head. He is outraged that — at one point in the production — “a minor character seizes the spotlight and proceeds to inveigh against ‘MAGA fascism,’ the gun lobby, ‘ICE disappearing people into the black hole of history,’ the likelihood that AI will ‘make us all obsolete,’ Rudy Giuliani, and ‘Democrats who keep voting to fund a genocide in Gaza.’” Yes, we live in “Trumpy times,” the critic admits, “when threats to freedom seem to accumulate every day, alarming Americans who have grown, you know, fond of democracy.” But an injection of raw polemics is just too much. There’s no nuance. Yes, there’s a crisis, but well-behaved theaters don’t do things like this — and to the Bard!

I asked for, and received, ASP Artistic Director Christopher V. Edwards’s response to the Globe review:

“When Shakespeare’s Macbeth was first performed around 1606, following the assassination of King Duncan in Act 2 – the audience would have been treated to the Porter character emerging from the world of 11th Century Scotland and talking about the modern events of 1600s London – with references to English tailors, and the ‘equivocator’ line often thought to be a reference to the Gunpowder Plot led by Guy Fawkes the year prior.”

“We saw it as our duty as stewards of this play to have our Porter (played by Dennis Trainor Jr.) break from the world of Cold War America and discuss the political matters of today – from artificial intelligence to global warming to the genocide in Gaza.”

“Don Aucoin of The Boston Globe clearly did not enjoy that portion. And he’s fully right to have his own opinion on it. But we wish he had been able to see that not as ’straining for relevance’ as he put it – Macbeth is clearly relevant enough for our own times to stand on its own two feet – but the exact opposite, as harkening to the tradition of the piece and how Shakespeare’s audiences would have engaged with this work itself.”

Kudos to Actors’ Shakespeare Project for a rare acknowledgement, at least among Boston area theaters, that these are not normal times. Political theater comes in many forms, from the circus-like satire of Bread and Puppet (currently touring in Texas, where NPR reports that a few audience members have walked out) to the capitalist critiques of Bertolt Brecht and Caryl Churchill, the activist antics of street theater, and the fact-based drama of the Living Newspaper and other strands of documentary theater. Different kinds of political theater aim at distinct goals: to provoke, inspire, shock, amuse, sustain believers, disrupt, and so on. During these dangerous days, how are our theaters reacting? The majority are choosing to play it safe, to hunker down and maintain business as usual. It sounds to me as if the ASP dared to do something different. To hold up a mirror to a nature that is overheating and an America that is drifting toward authoritarianism.

But Aucoin is part of the culture-industry contingent that knows that all will be well, that it is best to hang back and wait. “There will doubtless be many Trump-inspired dramas in the years to come. It would be best if they’re subtle enough to let the people in the seats connect the dots. As with saving democracy, the audience has a job to do.” How is he so certain that “Trump-inspired” shows are on the way? We have seen major universities, mega corporations, media giants, and tech firms bow to Trump’s will; instances of censorship are growing at record rates, along with rising levels of self-censorship. Fear, like courage, is contagious, particularly among the rich and powerful. Perhaps, by “Trump-inspired,” Aucoin assumes the arrival of dramas that will praise the heroic deeds of our fearless leader? Perhaps there will be subtle ones?

Aucoin rightly notes that audiences must do their job to save democracy. But don’t theater companies have a responsibility to protect democracy? To inspire people to fight for its survival? Ironically, Aucoin leaves out an important question: what is the job of the theater critic in these dark times? Apparently, it is to complain when a stage company doesn’t stick to the same old tame, apolitical script

October 8, 2025

Orwell’s Big Brother likes obedience in advance. Censorship is steamrolling along without the need for a rap on a finger, let alone a boot in the face. “Never before in the life of any living American have so many books been systematically removed from school libraries across the country,” warns PEN America in its invaluable report Banned in the USA: The Normalization of Book Banning. The motto for Banned Books Week (through October 11) is “Censorship is so 1984: Read for Your Rights.” The truth is, 1984 is au courant — it is among the most banned volumes in the world. So far, Americans have been dangerously complacent, complicit, or indifferent to the surge in book banning — a direct assault on the freedom to read that threatens to gut democracy and public education, normalizing fear by classifying books and writers as enemies of the state.

The nefarious process is coming along in this state. Objections to the holdings in Massachusetts libraries have more than doubled over the past three years, with the majority of objections churned out by organized movements (ideological pressure groups and government entities) rather than individuals. Among the titles that have been banned or challenged: Worm Loves Worm and This Book is Anti-Racist.

Is Massachusetts doing anything to protect independent voices in an increasingly hostile landscape for writers and readers? Our allegedly liberal state is spinning its wheels. Those who want to fight censorship should support the Mass Freedom to Read Coalition, a group urging state legislators pass a comprehensive Freedom to Read bill that “protects librarians and educators from harassment for doing their jobs, and protects authors, creators, booksellers, and publishers from economic harm due to censorship.” This is the third year the Massachusetts legislature has considered the bill, but it has never moved to a floor vote. Thirteen other U.S. states have passed legislation protecting the freedom to read — including Rhode Island in August of this year. But Massachusetts has not, though passage would seem to be a slam dunk. Why?

I asked Nicholas LaRue, co-leader of the Massachusetts Authors Against Book Bans coalition, about what’s behind the holdup. It turns out that — along with the inertia of politics as usual — it comes down to old-fashioned cowardice. “Our legislators don’t want to draw the ire of the administration in Washington more than they already have,” LaRue told me. “They don’t want all that dark money that’s being pumped into other states for primary candidates to come here. The feeling is, as long as we can keep our heads down and continue to make money, as long as the right people leave with smiles on their faces, the state is in a good position. Why rock the boat? Nobody is going to lose their jobs if we keep the status quo.” Still, LaRue has hope that this year the bill will pass.

This decision to hunker down also reflects our arts community’s passive posture. It is a mistake. From everything we have seen of Trump’s reactionary administration, inaction is targeted as a sign of weakness. “Repression lives off fear,” wrote Belgian-born Russian revolutionary, novelist, poet, prisoner, journalist, and translator Victor Serge. We are not going to protect the freedom to read — as well as many of our other freedoms — by playing possum in front of an authoritarian regime-in-the-making. It only makes us easier candidates for roadkill.

October 1, 2025

German poet/dramatist Bertolt Brecht testifying in 1947 before the House Un-American Activities Committee. Photo: Open Culture.

“As Trump increasingly targets the arts, artists are faced with the question of whether to speak out or keep their heads down” stated the introduction of a segment of a Sept 29 PBS NewsHour. Is anyone who has been paying attention surprised that America’s arts and culture establishment has decided, this time around with Trump, to glue its knees to the floor? New York Times Culture Reporter Robin Pogrebin summed up the creative industrial complex’s docile reaction to the administration’s ongoing assault on democracy, freedom of speech, and the arts: “You see a kind of — much more of a cowed, capitulating stance on the part of the art world, I think a sense of resignation. It may be just something they have to hunker down and weather for the next four years under Trump.” That last point raises an elemental question — what is going to be the condition of arts and culture after four years of Trump? After self-censorship becomes de rigueur, and fear and intimidation routinely undercut artistic freedom?

Don’t worry, be happy. Harvard University’s American Repertory Theater assures us that, with the assistance of its current presentation, 300 Paintings, “It’s time to laugh.” (Though I doubt there is much guffawing happening at Harvard, given Trump’s new effort to block all federal funding from going to the institution.) I agree that it is a damned good time for laughter, but the hilarity should aimed at the inane crudity of the enemies of democracy and freedom.

For chuckles of that type, McCarthy era version, watch this short (31 minute) and amusing dramatic reconstruction of poet/dramatist Bertolt Brecht’s testimony before the House Un-American Activities Committee on October 30, 1947. A Good Example: Bertolt Brecht and HUAC was shot in 1979 by local writer/actor/ producer David Rothauser with help from the Angry Arts Film Collective and Walnut Films. (Rothauser cast himself as Brecht, and he is quite good.)

Brecht’s responses consist of wry obfuscations and jokes. He often plays dumb or wanders into double talk about how any play that deals with modern times must include references to Marxism. He frequently blames sloppy translation for the committee’s “misunderstanding” of his work and his politics. Still, at the end of the session, Brecht was praised by HUAC chair Rep. John Parnell Thomas (R-NJ) for his cooperativeness. He flew to Zurich the day after the hearing.

Some of Brecht’s thoughts on the clumsy grilling are included in the film, including this chilling, prescient observation from his 1948 speech at Stockholm’s International PEN Club: “From the United States we will see the almost incredible news that some of their best writers will now be sent to jail. I sat next to them on the defendant’s bench in Washington two and a half years ago … my American colleagues were protected by the Constitution; it was the Constitution that was not protected.”

September 24, 2025

A mosque in Gaza destroyed in an Israeli airstrike, 20 February 2025. As of January 2025, Israel had destroyed 815 mosques and 19 cemeteries over the course of the Gaza war. Photo: Wikimedia

There’s been a debate about genocide, but not much discussion about the horrors of cultural genocide. And that silence is deeply disheartening. On September 18, PEN released the report All That is Lost: The Cultural Destruction of Gaza. Everyone in the creative industrial complex should read this terrifying document. It “examines the destruction or partial destruction of 36 cultural, historical, religious, and educational sites, and also includes three instances of deliberate book burnings and two cases of reported looting of archaeological artifacts … The war has inflicted a catastrophic blow to Gaza’s cultural life and heritage, with some of the most important cultural and religious landmarks in Gaza destroyed. Israel’s military campaign has resulted in the total or partial destruction of every university and college in Gaza and 11 libraries, including the total destruction of the Gaza Public Library, which housed 10,000 books in Arabic, English, and French.” Israel has systematically — and shamefully — set out to obliterate a people’s history, arts, and identity. It should be condemned: what the IDF has done provides a blueprint for efforts at cultural extinction elsewhere.

On a less apocalyptic level, the repression of the arts in Hungary and in Israel foreshadows the actions of the Trump administration. This approach draws on direct government intervention in the arts, media, education, and museum sectors. The administration appoints loyalists to major cultural institutions as it shifts funding towards projects aligned with its conservative ideology and cuts others, marginalizing non-conforming artists and institutions. Hungary serves as an authoritarian model for how Trump may want to structure the arts. Independent artists who have not already fled Orban’s fiefdom have organized a bohemian underground that the police keep under surveillance. That two-tiered division – the complicit and the non-complicit – may well soon surface in America. Artists who don’t censor themselves will be targeted as the “enemy within.”

Israel also serves as a model for intimidating free-thinking creators. According to a September 17 report in Haaretz, the government has suspended funding for Israel’s top film prizes, the Ophir Awards, because the movie that won Best Film honors this year, Shai Carmeli-Pollak’s The Sea, is about a Palestinian boy from the West Bank who journeys to see the sea for the first time. The Culture and Sports Ministry claimed that the film “defames” the IDF and Israel. According to the rules, The Sea will be Israel’s submission for the Oscar for best international feature.

Assaf Amir, the chairman of the Israeli Academy of Film and Television, is proud of the Ophir Awards’ gesture of defiance. Let’s hope that legions in America’s arts and culture community find the courage to speak out — and act decisively — against the Trump administration’s growing efforts to curtail artistic freedom. A recent issue of American Theatre details the admirable effort of artists and culture workers to organize nationwide under the banner of The People vs. Project 2025. Boston’s arts community has been puzzlingly mum in the face of repression, content to go about marketing its business as usual. For example, the American Repertory Theater tells theatergoers to book early because “Wonder Awaits” the arrival of its latest Broadway-bound musical. Shouldn’t someone in the arts community be concerned that its not so wonderful that authoritarianism sits around the corner as well?

September 17, 2025

Ben Shahn, Second Allegory, tempera on Masonite. 1953.

I went down to New York this weekend to check in on masterpieces by two of my favorite artists: the Theatre for a New Audience presented a moving production of Henrik Ibsen’s still salient blast at homicidal self-righteousness, The Wild Duck. And there was Burning Bright, a satisfying exhibition of the art of William Blake at the Yale Center for British Art, which owns a fabulous collection of the poet/printer/visionary’s works. What was odd about the Blake show was that the curators had decided to tone down acknowledging the writer’s rabble-rousing side; his rage at tyrannical authority, especially its violence and economic pitilessness. Also ignored: Blake’s utter disdain for what he saw as the cruel, coldly rational God of Christianity. Trump is very much in the rancid mold of Blake’s Nobodaddy – a hollow deity/father figure, transactional and ineffectual.

In contrast, the fusion of artist and activist are celebrated in the splendid show Ben Shahn, On Nonconformity at NYC’s Jewish Museum. Shahn’s political orientation was steadfastly leftist, his socialistic perspective critical of fascism and authoritarianism. His life and art were dedicated to economic equality and social justice, a commitment well dramatized in this exhibition, which could not come at a more propitious time in our history. Artists need to be reminded of their responsibility to question the powers-that-be; critics must get over their knee jerk dismissal of political art. A quotation from Shahn’s 1956-1957 Norton Lectures (written at the tail end of the McCarthy era) sums up the counter-argument: “Noncomformity is the basic pre-condition of art, as it is the pre-condition of good thinking and therefore of growth and greatness in a people. The degree of nonconformity present — and tolerated —in a society might be looked upon as a symptom of its state of health.”

As government repression increases, curtailing thought and action, spreading fear through intimidation, our artists should see it as their task to resist conformity, which inevitably means challenging official strictures regarding what can be seen and said. Shahn also writes in his Norton Lectures that an artist “must never fail to be involved in the pleasures and the desperation of mankind, for in them lies the very source of feeling upon which the work of art is registered.” The temptation is to stick to doling out pleasures. But desperate times are here for many, and our artists are called to be among the witnesses.

Note: I had a spicy conversation about the moribund state of arts criticism (looking at you, Boston Globe, New York Times, and NPR), the growing need for online magazines like The Arts Fuse, and my new venture, Viva La Book Review, with Ellen Clegg and Dan Kennedy on their “What Works” podcast. Check it out.

September 10, 2025

The AP’s recent decision to discontinue book reviews, compounded by cutbacks in book coverage in major national newspapers and magazines, is symptomatic of a book culture in serious decline. It is time for the empire of those who care about books and reading to strike back and do something about it. It is time to call in a rainmaker.

And one has arrived. I am pleased to be on the board of a new nonprofit organization, Viva La Book Review, which is dedicated to turn things around for book reviewing in our country’s community newspapers and online media. According to VLBR’s mission statement, the goal “is to foster thoughtful, well-crafted book criticism that supports a crucial open dialogue among reviewers, authors, educators, librarians, and above all American readers, raising issues critical to all readers, critics, and editors maintaining a healthy democracy.” Our funds and considerable know-how are fully committed to growing book coverage at the grassroots —in print, digital, and audio media — thus increasing the number, as well as the quality, of book reviews in communities across the country. Readers, writers, editors, and publishers need to come to the defense of the beleaguered book review: the effort will not only stimulate readership, but also strengthen threatened democratic values

What is VLBR’s strategy? Downright revolutionary: work with and/or train book critics, pay for book reviews in cooperating publications, subsidize and eventually expand the number of critiques. In addition, build up free educational resources for critics — provide tips on how to write effective book reviews, pick volumes to critique, and pull off a ‘mixed’ review. In the future, online conferences, one-on-one tutorial sessions, and seminars on the craft of book reviewing, led by veteran book critics, will become available. Assistance to local media regarding how to amplify the impact of reviews will be offered, as well as help with spreading the critical word in bookstores, libraries, social media, and other channels.

What am I, my fellow board members, and an impressive line-up of advisors, made up of professionals familiar with all aspects of book publishing, asking? That editors and reviewers in local media get the book coverage ball rolling by contacting VLBR at: contactvivalabookreview@gmail.com. Recently, The New Yorker‘s David Remnick wrote that arts reviews “have the blessing of thinking, of judgment—and thinking about what makes a work of art unique or brilliant or dull or even pernicious is an invaluable part of the job of criticism.” Viva La Book Review believes that the job of a reviewer is of indispensable cultural benefit. Join us in the fight to keep the blessings of thinking and judging around.

September 3, 2025

Another reminder of the bewildering spinelessness of the Boston arts community as the country is confronted with a slide toward authoritarianism. Last week, the National Coalition Against Censorship (NCAC) and the Vera List Center for Art and Politics (VLC) announced the Cultural Freedom Demands Collective Courage: A Nation-Wide Statement of Values and Principles for the Field of Arts and Culture. As of this writing, only two of the city’s arts organizations have signed on, even though the statement doesn’t even (dare) mention Trump.

Our theater companies continually proclaim how “bold” and “boundary-stretching” they are. But that is marketing hooey. When it counts, our stages have been — and remain — silent in the face of encroaching tyranny. The Lyric Stage is producing Our Town later this month. The irony is head-spinning: “our towns” in America are being starved of funds; our major cities invaded by deployments of the National Guard (Boston may be on Trump’s to-do list); immigrants grabbed off our streets and shipped to gulags in other countries without due process.

What explains the gutlessness? The inaction among too many liberal power centers during what dramatist Lillian Hellman would no doubt characterize as a “scoundrel time”? Fear, of course, fantasies that they will be able to “ride this out,” and a fatal lack of nerve and imagination that Trump and company have aplenty. Nothing stops them from attempting whatever they can dream of to really push boundaries and consolidate a stranglehold on power. In contrast, our theaters (and other arts institutions) keep their heads planted in the sand, doing what they always do. Praying that all of this unpleasantness will just blow over. And if it doesn’t, well, don’t panic: there will be well-heeled fascists willing to pay big bucks to be entertained on Broadway and elsewhere. You just have to self-censor what you put on stage.

For decades, creative institutions have assured us that they serve the community. Is this what the citizens of Boston want at this time? Have they been asked? No rabble-rousing town halls? No protests led by artists demanding the protection of creative freedom? No shows acknowledging rampant cruelty and the plutocracy’s attacks on democracy, working people, and fairness? No attempts to inspire resisters to keep on fighting for a sane future? The same old, same old — is that all we are called for now? Timidity rather than leadership? Commercial fare that ignores how our institutions and guiding principles are being melted down, as if audiences and the creative class can escape the corruption and ugliness by pretending it isn’t there. It will not work. What will? “Cultural Freedom Demands Collective Courage” — backed by serious coalition building and action. Business as usual is cowardice, and worse — complicity.

August 27, 2025

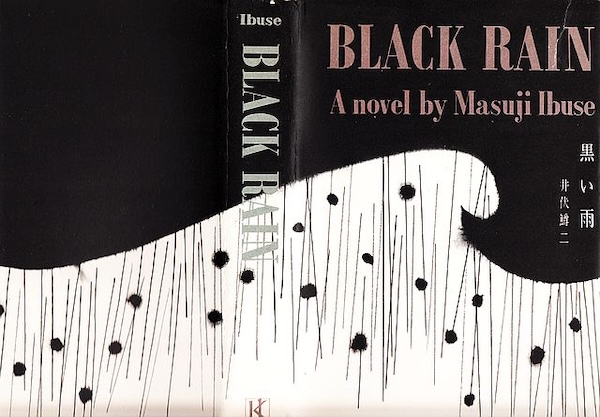

There have been articles on the 70th anniversary of Lolita as well as on The Great Gatsby and An American Tragedy turning 100. But, aside from an academic article or two, the media large and small has otherwise been silent on the 60th anniversary of the first serial publication (in the magazine Shincho) of Masuji Ibuse’s powerhouse novel Black Rain, an unsparing narrative about the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and its aftermath, which won the sought-after Noma Literary Prize in 1966. The neglect is odd, especially given that this month marks the 80th anniversary of the catastrophic strike. Perhaps the book’s graphic detailing about existence in extremis make it an upsetting read. Few works of literature offer as unflinching a vision — poignant rather than sentimental — of surviving through devastation that exceeded the limits of the human imagination at the time.

Born in Hiroshima Prefecture, Ibuse based his novel on journals and interviews with bomb survivors (hibakusha), conveying these experiences through what he called the “crudest kind of realism.” The storyline runs on two tracks: Shizuma Shigematsu writes down memories of enduring the bomb drop as he struggles to resume his life and unite with his family — his niece, Yasuko, and wife, Shigeko. He is undertaking this traumatic exercise to document that Yasuko escaped exposure to the “black rain” of radiation and therefore can marry an interested young man. But, five years after the bomb, Yasuko is starting to display symptoms of the disease. She is asked to report to the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission (ABCC), established by the Allied occupation in 1947 to collect data on the victims. The ABCC was only charged with recording cases like Yasuko’s — it provided cooperating victims no treatment. U.S. censorship regarding radiation sickness at Hiroshima lasted until at least 1948.

In 1989, Shōhei Imamura released a powerful film version of the novel, but he chose to focus on Yasuko’s plight. Ibuse’s novel, translated into English in 1966, offers a more extensive — and fiercely graphic — look at what life was like for the people in the city during and after the atomic bomb drop. The documentary approach can be tedious at times; do we really need to know the diet of middle-class Japanese citizens during the war? But there are amazing episodes, such as when — because the area’s crematoria were overwhelmed — Shigematsu was forced to hold funeral services over corpses that must be burned in makeshift fashion along the banks of a river.

Reading Black Rain now, it comes off as not just a historical novel, a memorable description of horrors, or a protest against the use of nuclear weapons. Ibuse, like Samuel Beckett, chronicled the shock of the new on human consciousness — the denial, bewilderment, hapless disorientation, and numbness generated by an encounter with human destruction beyond what had ever been dreamed possible.

August 20, 2025

In 2024, AI-generated “Shrimp Jesus” images proliferated on Facebook. Photo: Wikimedia

Reading Terry Nguyen’s thoughtful review in Art Review of Medium Hot: Images in the Age of Heat, a 2025 essay collection by the artist and filmmaker Hito Steyerl, I came across this provocative charge aimed at her blasé attitude toward what she sees as the pernicious proliferation of Al Slop: “It’s tempting to wonder, then, what we should dare hope for. Are there any artist collectives or start-ups resisting this widespread computational absorption? Is there legislation being passed to limit resource waste? Disappointingly, Medium Hot doesn’t cohere into a manifesto for the contemporary image worker – the artists, photographers, actors and creative laborers whose work is being subsumed into training data as their livelihoods are increasingly automated.”

What struck me is that this charge, of standing back from critiquing the forces that are undercutting the economic health of culture workers, can be leveled at about all arts critics today. The definition of the job has shrunk to quickie consumer guide or pop culture influencer — jabbing their thumbs up or down on whatever cultural product is under consideration. The notion that critics should take an activist role — posing alternatives to business as usual, lambasting corporate homogenization, condemning philistine editorial perspectives, recommending legislation to protect artists and resources — was a possibility in the past, when writing on the arts was taken seriously by society. But, unlike sports or political coverage, arts criticism has been confined to a narrow lane, a disastrously ironic development at a time the culture is in horrific crisis, with censorship and authoritarianism on the march.

What remains crucial at the moment, concludes Nguyen about our visual culture’s shift toward “probabilistic abstractions” … “is a strong ethical commitment to staying with reality.” There is something at stake for arts critics in what is happening today: they should accept their obligation to fight for our cultural health, to acknowledge a reality beyond the transactional — or be complicit with nurturing a dominant fantasy world of slop.

August 13, 2025

The latest bad news for book criticism – the Associated Press is getting rid of book reviews. From the service’s global entertainment and lifestyle editor: “I am writing to share that the AP is ending its weekly book reviews, beginning Sept. 1. This was a difficult decision but one made after a thorough review of AP’s story offerings and what is being most read on our website and mobile apps as well as what customers are using. Unfortunately, the audience for book reviews is relatively low and we can no longer sustain the time it takes to plan, coordinate, write and edit reviews. AP will continue covering books as stories, but at the moment those will handled exclusively by staffers.”

Book coverage is hovering at the edge at the Boston Globe as well. Nina McLaughlin’s local book column at the paper was recently canned. One reader draws my attention to the fact that “the daily Globe nowadays seems to consist mostly of promoting local novels, often first novels, which tend to be mysteries or romances — you know, beach reads — with special attention to the authors’ extra-literary thoughts and interests. The Sunday section does have a couple of reviews, but they are usually eclipsed in number by various columns. Also, I notice that Kate Tuttle is apparently not the Book Editor. She is described as ‘editing the Globe‘s book section,’ or sometimes, ‘she handles the Globe‘s books coverage.’” For many decades, the paper had a Book Editor: making the position freelance suggests we are moving closer to the final fade-out.

There is a new critic at the Globe, a “TV and pop culture critic.” A staff writer, of course — TV coverage is too important to leave to a freelancer! After all, a lot of people actually watch TV. Meanwhile, in the Globe’s Ideas section, there’s a long thumb-sucker about the mystery of why men don’t read fiction. Maybe they think books are not important. Who gave them that idea?

Could it be the people that treat arts reviews as disposable? The Globe’s film section has now decided to review trailers rather than major movies. A sampling of recent films left unreviewed by the newspaper: Weapons, a critically acclaimed and popular feature (it receives a rave from former Globe critic Ty Burr in the Washington Post), Final Destination: Bloodlines (a box office winner), Jane Austen Wrecked My Life, It’s Never Over, Jeff Buckley, and Shoshana.

August 6, 2025

The dance field was shocked and saddened by a freak accident at Jacob’s Pillow August 1. Gifted production manager Kat Sirico, who used they/them pronouns, was moving platforms on a dolly down a slope when they tripped and fell and was crushed by falling platforms. Sirico had been part of the Pillow family since a 2005 internship and was an experienced backstage professional. The Pillow cancelled performances the weekend of August 2-3. All of us at the Arts Fuse send our condolences to their family, friends, and colleagues.

The Boston Mayoral Forum on Arts & Culture, moderated by Jared Bowen, host of GBH’s The Culture Show, featuring Michelle Wu, Josh Kraft, and Domingos DaRose.

The Boston Mayoral Forum on Arts & Culture at the Strand Theatre on July 30 was valuable because it focused on how the arts will fare in the city during the corrosive Trump years. Most of the talk was wearily predictable, ranging from host Jared Bowen’s boilerplate questions to the usual pledges from the candidates (Michelle Wu, Josh Kraft, and Domingos DaRose) to celebrate arts and culture, increase inclusive access, and support urban spaces dedicated to artistic creation and performance. The lacunae were glaring and, unfortunately, telling. For example, there was no mention of the precipitous nosedive to come in tourism to the city, not only because of the fears of foreign vacationers to visit America, but also by the hard fiscal times wrought by Trump’s economic policies. (Kraft alluded to it.) As artists learned during and then after COVID, when the fiscal going gets tough, the arts and culture ‘industries’ are among the first to be cut. The survivors are the larger organizations that maintain their power by remaining as homogenized and risk-averse as possible.

Most important, there was no discussion about how Boston’s arts and culture community, with assistance from the city, will meet the crucial demands of the political present: defending democracy against the approach of authoritarianism. Artistic freedom is already under pressure; censorship is on the rise. In what ways might Boston — and our heretofore publicly silent arts community — work together to defend bedrock civic values? Will the cradle of democracy sit out the accession of autocracy? Or might our reticent culture workers and their employers decide to get off their knees and offer dissent?

July 30, 2025

Nicholas Alexander Chavez, Socorro Santiago, and the cast of Camino Real in the production at the Williamstown Theatre Festival. Photo Maria Baranova

Last week, the New York Times undermined mainstream arts criticism by reassigning four of its critics—of theatre, TV, pop music, and classical music—to other duties. What is particularly galling is that, in a memo on the paper’s decision, culture editor Sia Michel insisted that it was part of an ongoing effort to “expand” the Times’ cultural coverage “beyond the traditional review.” For decades, I have been arguing that the extinction of reviews seriously harms the cultural ecology, in part because it diminishes dialogue about the value of the arts. That said, many online sites, like The Arts Fuse, are picking up the slack. This is where first-rate reviewing will be found in the future. What left me flummoxed is this call to go “beyond the traditional review.” What does that mean?

The Boston Globe’s enfeebled arts coverage suggests what it means— arts criticism will morph into utter pablum. Case in point: Don Aucoin’s recent “Critic’s Notebook.” The piece is not a review, but an attempt to go ‘beyond,’ and it asks a good question: Where does dramatist Tennessee Williams’s greatness reside? But Aucoin proceeds not to answer it. He offers no analysis of his own, aside from spouting cliches, among them that the playwright’s “legacy seems up for grabs,” his scripts offer “so many doors to open,” and “there is always something new to discover about the work of Tennessee Williams.” Remove the quotes from director David Kaplan, and the piece is essentially a listicle of recent productions, with no attempt to deepen our knowledge of Williams. An article this lazy and mindless should be an embarrassment for a major newspaper – but it is business as usual for arts writing at the Boston Globe.

Let me tweak Aucoin’s question and provide a response. Why do we need the work of Williams now? The diverting Williamstown Theatre Festival production of the playwright’s mythopoetic circus, 1953’s Camino Real, offers a direct expression of his version of romanticism: “the ability to feel tenderness toward another human being, the ability to love.” It is this respect for care that the play’s characters – Don Quixote, Casanova, Lord Byron, and Esmeralda, among them — must learn to protect against the brutality of a fascist society. The potency of kindness — especially when it is confronted with inhumanity — is at the center of Williams’s dramatic vision. Few major American playwrights have examined that conflict so directly, so powerfully. And, in a world increasingly dominated by the virtual and the transactional, where cruelty has become the point of power — in Gaza, Sudan, Ukraine, and America — tenderness is under mounting threat. That is one reason why we need to see the work of Tennessee Williams – and why he is great.

July 23, 2025

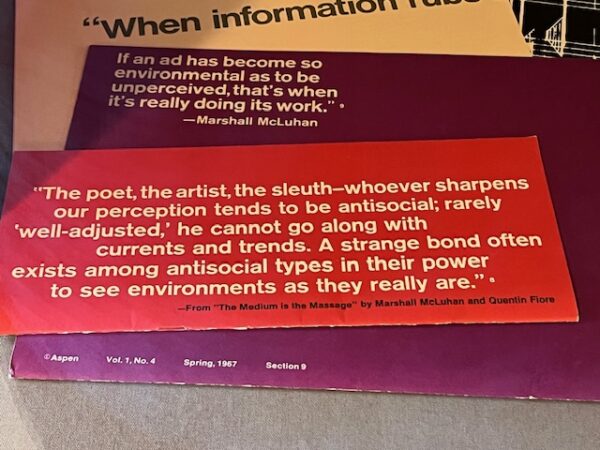

“Aspen: The Magazine in a Box vol. 1, no. 4,“ — author Marshall McLuhan, designer Quentin Fiore. In The Clark’s Bold By Design: Mid-Century Modern Graphic Arts exhibit. Photo: Bill Marx

First, the hopeful news. On July 16, the Healey-Driscoll Administration announced the launch of the Live Theater Tax Credit Pilot Program to support the development and expansion of live theatrical productions in Massachusetts. The program will award up to $7 million a year in tax credits for live theater productions. Its goal is to boost Massachusetts’ arts and culture ecosystem by attracting high-value theatrical productions that draw new audiences and support local industries.

But will this sweetener really energize our stage ecosystem? Boston’s small to mid-sized theaters were devastated by COVID and have never truly recovered. Larger theaters have been consolidating control and absorbing the available resources. A number of stated requirements for the tax credit—including “an estimated budget that demonstrates at least $100,000 of costs and expenses will be incurred in Massachusetts”—suggest that this program is tailored for the high rollers. Small companies are effectively shut out. And that means the Massachusetts theater scene will continue to flounder, both creatively and financially. Small stages are incubators for innovative talent and ideas; they are where the riskiest material is produced. Instead, the tax credit is designed to reward companies focused on producing commercial fare for New York, via pre-Broadway or pre–Off Broadway productions.

Obviously, the tax credit isn’t about strengthening theater as an art form—it’s about generating economic activity. Bowls of warm milk for the fat cats, as the press release spins it: “Through the Live Theater Tax Credit, we’re ensuring our theaters continue to deliver strong economic returns—creating jobs, filling hotels and restaurants, and strengthening communities across the state.” The announcement speaks of theater generating “joy” and “sparking imagination.” Nothing about stage productions as provocation, as art, as dissent. Marshall McLuhan states the counterpoint succinctly: “Whoever sharpens our perception tends to be antisocial” because they possess the “power to see the environments as they really are.” Why do we need theater? Because it delivers “strong economic returns”? This soulless, transactional blather erodes our understanding of the true value of the arts.

Funding for the arts is being clawed back. Free speech is under threat. Authoritarian forces are encouraging self-censorship and successfully curtailing protest. How can we fight back against oppression? Theater should be one answer. What would offer genuine assistance? A tax credit (and philanthropic support) for independent stage companies of all sizes willing to become part of the much needed resistance.

A thoughtful comment on this column from Jon Garelick:

I appreciate the pitch to make tax breaks available to smaller companies, but, really, pitching the arts as economic development may not be revolutionary but it’s not counter-revolutionary either. It means jobs: for playwrights, actors, set designers, and other theater professionals as welll as the workforce in the surrounding community. Pitching tax breaks as “provocation” and “dissent” and a way to stick it to the Man really doesn’t wash, sorry. Stick it to the Man who just gave you the tax break? How many musicians, carpenters, and actors have fashioned a sustainable livelihood by working in commercial theater? That is, when they weren’t waiting on tables or tending bar in restaurants that service the Theater District. Or, heaven forfend, invest the money they make from big budget films in independent film projects and their own community-based businesses. I don’t mean what’s good for Big Theater is Good for the USA, but $100,000 isn’t exactly Fat Cat expenditure. What’s the annual budget of the Central Square Theater, or other small theaters you could name? So, yes, let’s use that dirty money from the Fat Cats to produce Brecht or that production of “Mrs. Warren’s Profession” that you and I liked so much — or even something new! It beats robbing banks. https://www.bostonglobe.com/

My response:

All good points… but we should consider going beyond “business as usual.” Jobs, by all means, matter, but it’s clear that power is shifting in an authoritarian direction. The state claims it wants to resist this national move toward autocracy. Yet, the tax breaks—targeted at Broadway or off-Broadway-bound productions—are about maintaining the status quo.

This means more theater with little or no connection to the emergencies at hand. As of now, few Boston-area theaters dare to acknowledge the crisis I mentioned in the column’s final paragraph. Nothing in this “tax break” incentivizes a change in repertoire or artistic spirit. The larger theaters show little interest in Brecht or any material that examines urgent issues like war, peace, inequality, climate change, or broken economics. If the state, the arts community, critics, etc., are truly serious about protecting democracy, then they should put their money and/or energies where their mouths are.

Fascist Germany and Italy kept their cultural scenes alive in the same way conventional economies do (for example, Oban’s Hungary). There’s plenty of economic activity, especially for companies willing to ignore what’s happening in the police state and are content to serve up sanitized entertainment, or even praise the autocrat in charge. Of course, free expression is muted, and—as we see in this country today—people are taken off the streets by “deputized” thugs and thrown into jail.

Is pitching the arts as an economic good counter-revolutionary? No — as long as the more essential values of the arts are articulated — as they were not in the state’s PR release. To me, the tax break has been tailored to reinforce the mentality of an arts community that’s afraid of today’s challenge — so fearful of risk that it would rather be oblivious to danger. Or maybe the stage companies know something we don’t — it is all going to work out, just keep your head down and be quiet. Nothing to see here — congratulate yourself for turning a blind eye.

Might the state, or wealthy patrons who care about America’s future, step up and support an “underground” theater committed to defending democracy and other radical ideas? I don’t have high hopes, but it is worth throwing out for consideration.

July 16, 2025

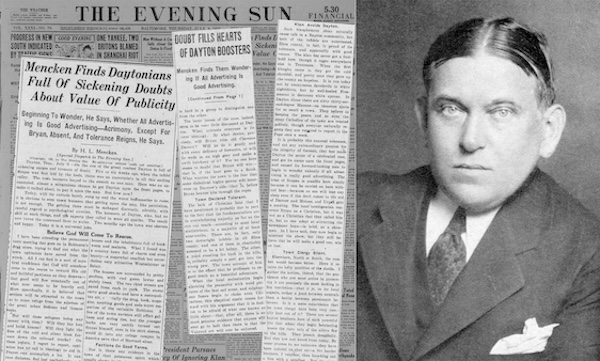

H.L. Mencken reporting in the Baltimore Evening Sun on the first day of the Scopes “Monkey Trial.”

A hundred years ago this week, tongue-slashing social commentator, acidic literary critic, and veteran reporter H. L. Mencken was hunkered down in Dayton, Tennessee during a heat wave, covering what he had proclaimed to be “the greatest trial since that before Pilate!” High school teacher John Thomas Scopes was being tried for violating a state law that forbade teaching evolution to young minds; the proceedings became a national sensation. The Baltimore newspaper for which Mencken worked, The Evening Sun, supplied Scopes’ bail. Mencken had earlier coined the term “The Bible Belt,” and he gifted this legal spectacular with a derisive label that has stuck ever since — “The Monkey Trial.”

At first, Mencken was pleasantly surprised by Dayton. “I expected to find a squalid Southern village,” he noted, “what I found was a country town full of charm and even beauty.” But, from the get-go, he saw that religious fundamentalists were in charge: “It was no more possible in this Christian valley to get a jury unprejudiced against Scopes than would be possible in Wall Street to get a jury unprejudiced against a Bolshevik.” Mencken’s reportage has been accused of being crude and reductionist — the march of Christian Nationalism today, via a combination of realpolitik and fear, underlines the prescience of his vision of religious power-mongering and censorship.

As for the secular forces opposing religious fundamentalism, Mencken offered this trenchant characterization in his 1956 book Minority Report: “Democracy, in the last analysis, is only a sort of dream. It should be put in the same category as Arcadia, Santa Claus, and Heaven. It is always a mistake to think of it as a reality. It never really exists; it is simply a forlorn hope.” A hundred years on, that hope is looking scarily fragile.

July 9, 2025

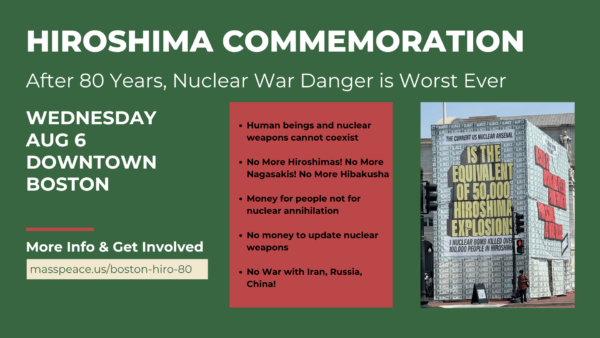

August 6th marks the 80th anniversary of the U.S. military dropping an atomic bomb, from the B-29 bomber Enola Gay, over the Japanese city of Hiroshima. Three days later, Nagasaki would suffer the same fate. Boston’s arts community has taken little notice of the occasion, which is not surprising. America’s performing arts culture is often indifferent to issues of war and peace, particularly when it requires confronting our problematic history of violence. It makes for challenging, rather than empowering, theatrical experiences.

Compelling plays about the bombings exist, such as Michael Mears’ The Mistake and Minoru Betsuyaku’s The Elephant, which tells the story of an atomic bomb survivor (hibakusha) battling health issues along with a society eager to forget the catastrophe. Despite their relevance and power, these scripts—and others like them—are not being produced here.

That said, a coalition of Boston-area peace, justice, and environmental organizations will mark the date with a major event. I also highly recommend Greg Mitchell’s new documentary, The Atomic Bowl: Football at Ground Zero — and Nuclear Peril Today, which will begin streaming on PBS on July 12. For many years, Mitchell has written perceptively and with investigative depth about Hiroshima and Nagasaki; his 1996 book with Robert Lifton, Hiroshima in America: Fifty Years of Denial, is a favorite of mine.

There’s not much buzz about the WWII A-bombs here, but it’s another story in Japan. President Trump’s recent comment, comparing his decision to strike Iran’s nuclear facilities—“That hit ended the war. I don’t want to use an example of Hiroshima, I don’t want to use an example of Nagasaki, but that was essentially the same thing”—has drawn plenty of criticism, including invitations for Trump to visit the cities. I’m not holding my breath on that one. In his soon-to-stream doc, Mitchell points out that Barack Obama was the first—and, to date, only—sitting U.S. president to visit Hiroshima. He did not, however, travel on to Nagasaki.

July 2, 2025

One sign of a dystopian future — an acquiescence to library book purges. Ira Wells’ excellent study, On Book Banning: Or, How the New Censorship Consensus Trivializes Art and Undermines Democracy, chronicles a recent exodus. In September 2023, the school board of the Erindale Secondary School in Mississauga, just west of Toronto, took part in “a new equity-based book weeding process.” Overnight, 50% of the school’s holdings were removed from its library shelves. According to the CBC, the vanishing was part of a regional decision “intended to ensure library books are inclusive … and [it] appears to have led some of the schools to remove thousands of books solely because they were published in 2008 or earlier.”

The offending volumes were deemed a “health hazard,” so they had to be disposed of immediately. And, because the culled books were “causing harm, they [the libraries] were forbidden from donating them to charity.” Not only was there the fear of mold, but the books were not “inclusive, culturally responsive, relevant or accurate (racism, stereotypes, microaggressions, lack of representation or erasure of communities, slurs, oppression, etc.). Fahrenheit 451 got it wrong: books won’t be burned, because big bonfires attract too much attention. Condemned material will be (quietly) trucked off to dumps so it can’t be reused. It is unknown how many thousands of books were trashed by the 259 Canadian schools involved.

Wells’s book discusses the perniciousness of book banning across the ideological spectrum. He emphasizes that both sides are committed to instituting a cutthroat political conformity under the guise of “protecting children from harm.” He helpfully distinguishes between different censorship strategies: parental advocacy groups in Florida push public efforts to eliminate books in libraries; institutional efforts in Canada are much more secretive.

“Book banning,” Wells argues, “is a form of coercion, an attempt to not only control what children read, but also what they think.” And he points out that censorship is inevitably accompanied by violence. Librarians have been fired, and in some cases killed, because of the books on their shelves. “No one should be threatened for providing access to information,” Lisa Radha Vohra, Director of Collections and Membership Services at the Toronto Public Library, told him, “I’m not so naïve to think it couldn’t happen here.” Is anyone clueless enough to believe that it couldn’t happen here?

June 24, 2025

Public art by Martin Firrell presented on digital billboards in the UK in 2019.

Why is the Boston-area artist community so complacent in the face of oppressive censorship and draconian budget cuts? One dismaying answer was provided by a recent opinion piece warning against autocracy on the march in the Commonwealth Beacon. It was signed by Michael Bobbitt, director of the Mass Cultural Council; Brian Boyles, executive director of Mass Humanities; Kayla Coleman, executive director of the New England Museum Association; and Emily Ruddock, executive director of MASSCreative. Unfortunately, those expecting fire in the belly will end up wondering if the pilot light in the oven is lit.

Here is the quartet at its fever pitch: “Our jobs often find us celebrating the successes that unfold in communities that embrace the arts and the humanities. Today, however, we must sound the alarm. In its first 100 days, the Trump administration took steps that represent a clear and present danger to the cultural vitality of the nation and, we believe, to our democracy. We call on the people of New England to respond proactively to these threats.” How are “the people,” particularly arts organizations, supposed to fight back? The piece doesn’t mention protest, resistance, activism, defiance, or mass demonstrations. Our leaders offer no concrete ideas or pragmatic suggestions about how “the people” are supposed to galvanize dissent. No demands are made that repertoire be changed or shaken up to confront the threat. The alarm bell is softly sounded — as if we are expected to keep on sleeping through it.

“We call on public and private supporters to honor the history of New England by celebrating our right to courageous dissent.” Celebrate? Throw parties? That is nonsense. People will join with an arts industry that is seen to be fighting for its survival. And that means the cultural powers-that-be must get off their privileged butts and encourage, organize, and fund protests fighting to preserve the arts and democracy, events that defy authority, that short-circuit business as usual. (Hint: check out our review of The War of Art: A History of Artists’ Protests in America.)

Decades of bureaucratizing and commercializing (every creator an entrepreneur) have turned the artistic community scarily obedient, trained to tumble robotically through hoops for the sake of garnering grants for officially approved advocacy and education goals. The muscles ordained for disobedience, for defiance, for screaming ‘hell no,’ have atrophied. The state’s arts leaders’ weak-kneed rhetoric is symptomatic of that paralytic anemia. The hour for battling back is growing late. New England’s cultural sector needs to snap out of it and tap into its rebellious muscle memory, to flex its brawn as art has done over the centuries when faced with a crisis. We need to bite — as hard as we can — the hand that refuses to feed us, that wants to steal our liberty.

Evidence that Major Arts Organizations Don’t See Autocracy as a Problem: The subject line for the latest marketing email flogging the American Repertory Theater’s production of its Broadway-bound musical Two Strangers (Carry a Cake Across New York) — “We Ask the Tough Questions: What’s Your Favorite Rom-Com?”

June 19, 2025

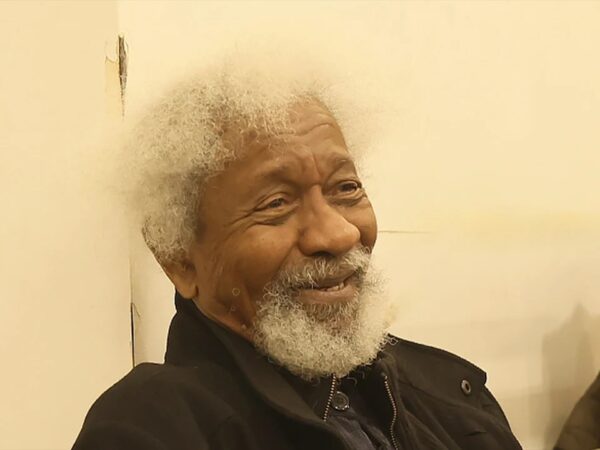

The late East African writer Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o. Photo: Wiki Common

The encomium is overused, but Kenyan author Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, who died on May 28 at the age of 87, was indeed a giant whose writings and actions fused the political and the literary. His iconoclastic perspective, as a novelist, dramatist, activist, and social critic, created the groundwork for debates on the decolonization of literature and thought (in Africa and elsewhere), a commitment that runs through the essays in his latest book, Decolonizing Language and Other Revolutionary Ideas (published last month). “A people can be deprived of wealth and power,” Ngũgĩ argues in the title piece, “but one of the worst privations is depriving them of the means of perceiving and articulating their deprivation, and thereby developing a vision and strategy and tactics for fighting it.”

In America, Ngũgĩ is better known as a novelist than as a dissident dramatist. That is unfortunate, particularly now, given that his stage productions are powerful examples of defying autocracy. In 1977, he and Ngũgĩ wa Mirii co-authored I Will Marry When I Want, an anti-government script produced by the Kamiriithu Community Education and Cultural Centre, an experimental theater — built in a Kenyan village and maintained by peasants, factory workers, and primary school teachers — dedicated to presenting dialogue on cultural and political issues. Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o was arrested and carted off to a maximum-security prison, where he would be kept without trial for nearly a year. During that period, he wrote, in secret (reportedly on toilet paper), two books: his prison memoir, Detained: A Writer’s Prison Diary, and the powerhouse novel Devil on the Cross, a critique of capitalist corruption that demanded the end of dictatorship.

In 1982, Ngũgĩ’s musical Mother Sing For Me was set to be staged at the Kamiriithu Centre, but Kenyan dictator Daniel arap Moi forbade its production. The higher-ups took censorship a destructive step further: the Centre was demolished by the police.

Since Trump’s return to power in January, there has been scant protest against the threat of encroaching authoritarianism in America’s theaters. Ngũgĩ‘s risk-taking should serve as an inspiration for our stages to speak out, despite the pressures from corporations and various vested interests for them to remain silent — and complicit.

June 11, 2025

Dramatist Caryl Churchill. Photo: Marc Brenner

As for the power of artists to inspire dissent, English dramatist Caryl Churchill recently withdrew a script for production at London’s Donmar Warehouse because one of the theater’s major sponsors, Barclays, has alleged links to defense companies supplying arms to Israel. Unsurprisingly, her decision has not been reported widely in our country’s mainstream media. But the choice of a renowned British dramatist to refuse a production—on humanitarian grounds—draws much-needed attention to the relationships between theater companies and their corporate funders. In Churchill’s words, “theatres used to say they couldn’t manage without tobacco sponsorship, but they do. Now it’s time they stopped helping advertise banks that support what Israel is doing to Palestinians.”

According to The Guardian, “more than 300 arts workers and creatives, including the actors Alfred Enoch, Samuel West, Tim Crouch, Harriet Walter, and Juliet Stevenson have signed an open letter supporting Churchill’s decision.” Aside from stimulating the debate about Israel’s actions in Gaza, Churchill’s choice highlights how giant banks have long gotten away with using arts sponsorships to improve their public image. For example, JPMorgan Chase was identified as the world’s top fossil fuel financier in 2023, committing $40.8 billion in that year alone. Other humongous U.S. banks, such as Bank of America, Citi, and Wells Fargo, are also listed among the world’s largest lenders to big oil. Perhaps, someday soon, a noted American dramatist will publicize that issue by refusing to have a play produced by a theater company that receives money from banks that are funding the despoliation of our world.

As Mark 8:36 asks, “For what shall it profit a man, if he shall gain the whole world, and lose his own soul?” At this point, what with global warming accelerating and oligarchy on a quick march, it is a question those who run arts organizations should be asking themselves.

Note: This just in — Bank of America, a longtime supporter of Trinity Repertory Company, recently made a $3 million commitment to support transformational capital improvements and artistic programming at the theater, which was announced at the theater’s 2025 Pell Awards Gala on Tuesday. “At Bank of America, we believe that investing in the arts has a decisive impact on the community,” said Kevin Tracy, president of Bank of America Rhode Island. “Trinity Rep is a vital organization that makes the arts more accessible through bold and original theatre and stimulating education programs. We are eager to support Trinity Rep as they make major building renovations that will keep this important cultural resource in downtown Providence providing entertainment to Rhode Islanders of all ages.”

In 2024, Bank of America provided financial commitments to fossil fuel interests totaling almost $34 billion. This amount places them in the top three fossil fuel financiers, along with JPMorgan and Citi, according to Utility Dive and NBC News.

May 28, 2025

One of the Ibo Yam Knife masks worn in stagings of the Okumpka plays. During these performances, youth had dramatic license to criticize questionable behavior of elders without fear of penalty. At the Fitchburg Art Museum. Photo: Bill Marx