Film Review: “The Shrouds” – Casket Case

By Nicole Veneto

If you think the world’s gotten a lot colder in the last couple years, you’re not alone. David Cronenberg feels it too.

The Shrouds, directed by David Cronenberg. Screening at the Coolidge Corner Theatre and the Landmark Kendall Square Cinema.

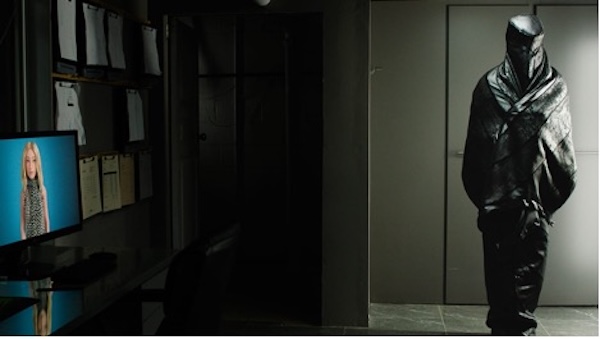

Karsh (Vincent Cassel) dons The Shrouds. Photo: Janus Films

When Denise Cronenberg died in May 2020, David lost not only a sister but a creative partner. His costume designer from The Fly through Maps to the Stars, Denise was responsible for some of Cronenberg’s most iconic wardrobe pieces, including the Mantle twins’ surgical gowns in Dead Ringers and Rosanna Arquette’s fetishistic leg braces in Crash. Three years prior, David’s wife of 43 years, Carolyn Zeifman, had died of cancer. Like Denise, Carolyn had also helped David realize his visions, first as a production assistant for Rabid and then as assistant editor on The Brood and Fast Company. Women are key players in Cronenberg’s films on and off the screen but, as with any male creative, the role women play in their lives and work can be complicated terrain. Infamously, The Brood was inspired by Cronenberg’s divorce from and custody battle with his first wife, Margaret Hindson, who had worked on two of his early shorts as a sound recordist. We don’t know whether Hindson is alive or dead, but her legacy is immortalized in the image of Samantha Eggar licking the viscera from her humanoid rage-tumors.

These women haunt the periphery of The Shrouds, Cronenberg’s late-period exercise in mourning, conspiratorial thinking, and self-criticism. Similar to his previous effort, Crimes of the Future, The Shrouds is only conceptually a horror film. There are mutilated bodies, unexplained bone growths, and decaying corpses, but these all serve as thematic means to satirical (and reflective) ends. This may be Cronenberg’s most introspective outing, a critical interrogation of his own fleshy philosophy and the more nefarious impulses that may accompany the creative process. Viewed in conversation with his other films, The Shrouds is considerably colder about technology’s relationship to the body, probing a deeply unerotic world where human connection has become a matter of digital interfaces, unlimited screen time, and competing corporate interests.

The director’s stand-in is grief-stricken entrepreneur Karsh (Vincent Cassel, sporting Cronenberg’s trademark silver coiffure), a man who’s made a profitable career by exhibiting the bodies of others, particularly that of his deceased wife Becca (Diane Kruger). Once a producer of “industrial videos,” Karsh’s latest business venture is GraveTech, an app that allows its users (Karsh included) to watch their dearly departed rot away in wired graveyards thanks to camera-equipped burial shrouds. (That one of these cemeteries is located in the backyard of a restaurant he owns is a testament to Karsh’s perversely capitalist priorities. That he drives a Tesla is another.) Karsh intends to franchise GraveTech overseas with the help of wealthy foreign investors, but when an act of sabotage desecrates the aforementioned grave plot where Becca is buried, Karsh’s tooth-rotting grief shifts from enterprising corpse voyeurism to untangling a corporate conspiracy that turns up more questions than answers.

Written after Carolyn’s death, Cronenberg has metastasized his own grief into a sardonic drama where the tension between creation and exploitation finds analogs in the director and his protagonist. Karsh is a man haunted by his wife’s image, both in the form of her twin sister Terry (also Kruger) and in his AI assistant Hunny (Kruger yet again), a hideous Meta avatar who has been designed in Becca’s likeness. GraveTech is Karsh turning bereavement into an investment opportunity — a particularly morbid case of a man transforming (immortalizing) his muse’s image into a consumer product. He laments the loss of her body — “the only place I really lived” — whenever Becca visits him in his dreams, each time missing a limb, a breast, and a functional hip due to experimental cancer treatments. (Notably, Karsh almost exclusively refers to Becca as a “body” throughout the film.) And, as Becca proves to be the common element linking GraveTech’s international expansion with its sabotage, Karsh’s paranoia melds with jealousy when a business rival turns out to be her former oncologist/ex-lover.

Karsh (Vincent Cassel) looking over his entrepreneurial grounds in The Shrouds. Photo : Janus Films

The same can (and has been) said of Cronenberg to a certain extent, though the director has denied any one-to-one correlation with his fictional counterpart. Yet modelling Karsh so much after himself suggests a conscious awareness for how the women in his life figured into his work. After all, the last time a woman inspired one of his films he reimagined her as a vengeful she-devil in a twisted version of Kramer vs. Kramer. (It’s also entirely possible that Terry’s embittered ex-husband Maury (Guy Pearce) represents yet another facet of Cronenberg.) Karsh and Cronenberg may be brothers in mourning, but they diverge in how they’ve decided to resurrect their muses post-mortem. The women of The Shrouds aren’t just commodified memory images, they’re white rabbits beckoning Karsh deeper into 21st century psychosis. Like another famous film about a man haunted by doppelgängers, chasing a woman’s image induces a case of Vertigo; to paraphrase Cronenberg, falling down rabbit holes is its own grief strategy.

As The Shrouds morphs from speculative sci-fi with an autobiographical-bend into an elusive conspiracy thriller, there’s a high chance casual and horror hungry audiences will be left cold. This is by design. If anything at all, The Shrouds is a litmus test in whether you understand what Cronenberg’s entire deal is. In broader terms, his thesis examines how the internal takes on external form — how modernity inscribes itself onto the body and vice versa. All body horror owes a debt to Canada’s Baron of Blood, but the truth is that Cronenberg’s interests have never been about grossing you out. He has a vast respect for bodies and their transformative potential, hence his preference for the term “body beautiful” over “body horror.” But if “body is reality” in Croenberg’s world, what happens when our current reality is so enslaved to technocratic designs that we hold Teslas in higher regard than people’s bodily autonomy above (and below) ground?

Whatever erotic possibilities between flesh and technology posited by Crash have diminished two decades into the 21st century; corporeality is subjugated to whatever the algorithm and its Silicon Valley overlords dictate. Sexual desire has been sublimated into the hysterical white noise on our apps. The only thing that gets us off nowadays are conspiracy theories. Thus the film’s sole sex scene reverses the one between James Spader and Deborah Kara Unger in Crash. Karsh’s day to day life is as sterile and automated as his choice of vehicle (a deliberate creative choice some have mistaken for frivolous product placement), a techno-futurist tomb of his own making designed by Carol Spier. Returning cinematographer Douglas Koch swaps Crimes of the Future’s intestinal hues for a deliberately subdued color palette, invoking the placidity of our own digital apocalypse. If you think the world’s gotten a lot colder in the last couple years, you’re not alone. Cronenberg feels it too.

Grief has supplied Cronenberg the opportunity to once again diagnose the modern condition. That he’s also used it as a springboard to reflect on his own corpus and the women who now exist as memory images within it is an added stroke of genius. We’re in the twilight years of an entire generation of filmmakers, many of whom are struggling to find funding as the clock runs out. We’ve already lost one David this year. We owe it to the other not to wait until after he’s gone to see his late-period films on their own (burial) grounds.

Nicole Veneto graduated from Brandeis University with an MA in Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, concentrating on feminist media studies. Her writing has been featured in MAI Feminism & Visual Culture, Film Matters Magazine, and Boston University’s Hoochie Reader. She’s the co-host of the podcast Marvelous! Or, the Death of Cinema. You can follow her on Letterboxd and her podcast on Twitter @MarvelousDeath.

A thought-out and sterling defense of a film I found confusing, tiresome, off-putting. I don’t like The Shrouds more but I respect it more from reading your review.