Book Review: “Doc Watson: A Life in Music” — An Inspiring Story

By Gerald Peary

Check out the book to absorb the trajectory of Doc Watson’s career from impoverished guitar player to becoming an icon of Americana and a repeat winner of Grammy Awards.

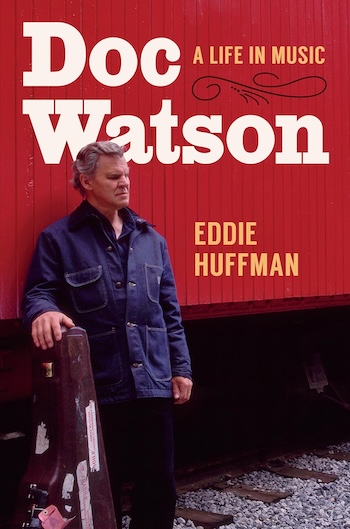

Doc Watson: A Life in Music by Eddie Huffman. The University of North Carolina Press, 288 pages, $30.

I’m fortunate to have seen Doc Watson play twice in the mid-1960s, once solo, once with his son Merle. I had great seats both times in an intimate folk club and, as practically everyone else, I was deeply moved by Watson’s astonishing repertoire of traditional Southern songs, his virtuoso guitar picking, and his so modest and genial manner, as if he was playing to down-home friends in his Blue Ridge Mountains living room. I projected on him an inner glow, a celestial glow.

I’m fortunate to have seen Doc Watson play twice in the mid-1960s, once solo, once with his son Merle. I had great seats both times in an intimate folk club and, as practically everyone else, I was deeply moved by Watson’s astonishing repertoire of traditional Southern songs, his virtuoso guitar picking, and his so modest and genial manner, as if he was playing to down-home friends in his Blue Ridge Mountains living room. I projected on him an inner glow, a celestial glow.

Was I duped a bit? As I read Eddie Huffman’s biography, Doc Watson: a Life in Music, I wondered if there was any dirt in Doc’s seven-decade career, ending at his death in 2012 at age 89. Well, there was one musician in the book who complained that he wasn’t always paid on time. And maybe Watson took advantage of his blindness to guilt-trip Merle into being on the road with him. And there was an occasion after Merle’s tragic death when Doc wasn’t available to his mourning wife in Boone, North Carolina, choosing to play around America to suppress his deep sorrows. For that, Doc was ever-apologetic. Otherwise? He played his music, he minded his business, he adored his family, he worshipped his wife, and he was kind to everyone. Doc Watson was truly beloved, by hundreds of professional musicians and by the locals back in Boone. Nobody ever accused him of having an attitude or putting on airs.

So Doc Watson: A Life in Music is a hagiography. But what else could it be? Though published by the University of North Carolina Press, Huffman’s work is not academic at all. It’s a solid piece of journalism, well-researched with straight-forward writing. And it’s musically knowledgeable enough. Huffman chooses to tell Watson’s life chronologically, and this becomes plodding at times, moving from concert to concert, album to album. And what can I say? Although I applaud Watson’s clean Christian living, it doesn’t always make for a breathtaking personal story.

But it’s assuredly inspiring what happened in Watson’s early years. Born in 1923 into an impoverished mountain family — no electricity, no running water — Arthel (that’s his real name) became blind soon after birth. That could have been it. But his father, named General Watson, practiced tough love. “He’s got to learn like the rest of us,” General declared. “I’m gonna take him out and put him to work.” And Arthel responded positively to having duties, to be involved in life. Huffman: “His responsibilities included cutting up kindling, feeding livestock, and digging up roots and stumps.” Later on, he would become a master electrician.

Meanwhile, Arthel grew up in an extended family filled with amateur musicians playing and shouting out old-time songs. One day, the Watsons got a Victrola 78 RPM record player and the voices of Jimmie Rodgers and the Carter Family floated into Arthel’s house. Arthel was overjoyed. More good news: fifty or sixty records were inherited from an uncle. Said Huffman: “A common thread running through many of the records was exciting, enthralling guitar playing.” Then his dad came through. General got Arthel a harmonica. Then a homemade banjo. Arthel took the banjo with him when leaving home to reside at the State School for the Blind and Deaf. There he was maltreated and undermined as he’d never been at home. But several teachers exposed the students to innovative music like Django Reinhardt. And there was radio, where Arthel first heard and responded to Black music: W.C. Handy’s “Saint Louis Blues,” a woman singer doing “Stormy Weather.”

On a school break, Arthel took his banjo into downtown Boone and started busking. But he had aspirations to take up the guitar. So General borrowed a relative’s truck, and father and son drove thirty miles east to a furniture store which also sold instruments. Arthel walked out with a twelve-dollar Stella guitar. Soon he was playing intently and listening obsessively to records of musicians who inspired him. It’s exciting to know that he not only purchased more Jimmie Rodgers and the Carter Family but he actually bought “race” records by Gus Cannon and the Jug Stompers and bluesman Blind Boy Fuller and Skip James. You can surely hear both white and Black in his future music. Probably the biggest Black influence on both him and Merle: the gentle country blues of Mississippi John Hurt.

One day Arthel was invited to guitar pick on local radio. As the story goes, the radio announcer called out for a more appealing name and a 13-year-old girl shouted back, “Call him Doc.” Soon “Doc” Watson made a name for himself around rural North Carolina as his guitar playing grew better and better and really better. And finally: The Break. He teamed up with an old-timer banjo picker named Thomas Clarence Ashley. In 1960, musicologist Ralph Rinzler came from New York in search of Ashley because of a legendary 1929 record, “The Coo Coo Bird.” Rinzler found Ashley, who was thought dead and, in the process, also took notice of Ashley’s blind musical partner. Rinzler produced their debut LP for Folkways, Old Time Music at Clarence Ashley’s.

In program notes, Rinzler aptly described the talents of Watson: “…unusually gifted both musically and intellectually. His memory for tunes and texts is phenomenal and his technical proficiency on a variety of instruments is absolutely staggering.… He has developed a number of distinct guitar techniques of his own in marvelously unorthodox ways.” A writer about Doc Watson, first solo album for Vanguard in 1964: “In a single concert he covers almost every feature of the Appalachian music complex, including blues…spirituals…ballads. Dance numbers and, perhaps best of all,…dazzling instrumental pieces.”

At this point, can I say to readers check out the book to absorb the trajectory of Watson’s career from impoverished guitar player to becoming an icon of Americana and a repeat winner of Grammy Awards? It’s undeniably an American Dream story, and didn’t Helen Keller herself once speak at Watson’s Blind and Deaf school lecturing the students that they could succeed?

The tragedy and darkness in Watson’s life is all about Merle. His son started out fine, a prodigy as a teenager playing guitar like his pa. Ultimately, he was almost as brilliant an instrumentalist, and the Watsons playing synchronously, trading licks, were aptly described as “one hand with ten fingers.”

In early days, Doc Watson had to strategize how to travel to each concert, often riding for many lonely hours on a bus. Then Merle Watson in his late teens became the designated driver as they navigated America, and he also led his father on and off stage. At first it was fine, but Merle definitely came to regret his obligations. He felt taken advantage of, partly because he had some discomfort with the arrangement — his father was the acclaimed headliner, he was the backup. But then Merle didn’t love audiences the way Doc did. An unsmiling, non-talking presence in concerts, Merle often just wanted to be home in Boone, working construction. Unlike his steady dad, Merle also had a chaotic, destructive side, running through women and wives, boozing and doing cocaine, playing with guns, being arrested for shooting out street lights.

He was probably a bit drunk when he tipped over his tractor in 1985. He fell under it and it crushed him. Neither of Merle’s parents ever got over his death at age 36. The only consolation is the MerleFest in North Carolina, a wildly successful annual music festival in his memory.

And Merle’s bereaved dad? Doc Watson just kept performing, doing much-loved concerts for another 27 years. “The most rewarding thing of my life was to do a song that I loved dearly,” said Doc, “that was dear to my heart, as they say, and find that people were sometimes in tears from the emotion from the good old ballads and songs.”

Gerald Peary is a professor emeritus at Suffolk University, Boston; ex-curator of the Boston University Cinematheque. A critic for the late Boston Phoenix, he is the author of nine books on cinema; writer-director of the documentaries For the Love of Movies: The Story of American Film Criticism and Archie’s Betty; and a featured actor in the 2013 independent narrative Computer Chess. His last documentary, The Rabbi Goes West, co-directed by Amy Geller, played at film festivals around the world, and is available for free on YouTube. His latest book, Mavericks: Interviews with the World’s Iconoclast Filmmakers, was published by the University Press of Kentucky. With Amy Geller, he is the co-creator and co-host of a seven-episode podcast, The Rabbis Go South, available wherever you listen to podcasts.

Tagged: "Doc Watson: a Life in Music", Americana, Doc Watson, Eddie Huffman, Folk