Book Review: “Banal Nightmare” — A Smart Lampoon of the White and the Privileged

By Ed Meek

Although novelist Halle Butler portrays the lives of millennial women (and men) as unhappy, anxious, and stressed, she does so in a highly entertaining way.

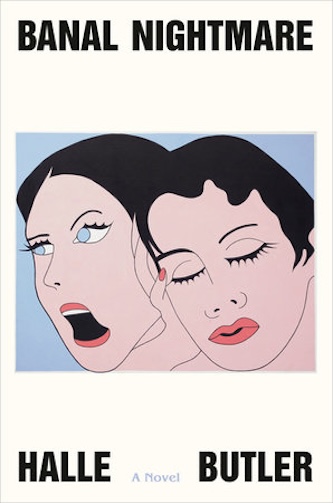

Banal Nightmare by Halle Butler. Random House, 336 pages, $28

Halle Butler is a screenwriter and novelist. She co-wrote two screenplays for independent movies and she has published three novels. She was born in Bloomington, Illinois and lives in Chicago. The New Yorker labeled The New Me, her second novel, a “definitive work of millennial literature.” The Chicago Tribune called her first book, Jillian, “the feel-bad book of the year.” Butler has her thumb on the pulse of the point of view of educated professional white women in their thirties and their partners (professional minority women should also relate to the world of Banal Nightmare). Although Butler portrays the lives of millennial women (and men) as unhappy, anxious, and stressed, she does so in a highly entertaining way. It helps that her characterizations and cultural comments are both accurate and funny.

Halle Butler is a screenwriter and novelist. She co-wrote two screenplays for independent movies and she has published three novels. She was born in Bloomington, Illinois and lives in Chicago. The New Yorker labeled The New Me, her second novel, a “definitive work of millennial literature.” The Chicago Tribune called her first book, Jillian, “the feel-bad book of the year.” Butler has her thumb on the pulse of the point of view of educated professional white women in their thirties and their partners (professional minority women should also relate to the world of Banal Nightmare). Although Butler portrays the lives of millennial women (and men) as unhappy, anxious, and stressed, she does so in a highly entertaining way. It helps that her characterizations and cultural comments are both accurate and funny.

The novel follows a thirty-something woman, Moddie, who breaks up with her boyfriend of ten years after he has started seeing someone else. The new girlfriend, Gracie, gets along well with Nick’s friends whereas Moddie does not. We learn that Nick’s best friend, Alan, sexually assaulted or raped Moddie. She told Nick about the abuse but he refused to believe her. This caused a rift between them. To help herself deal with the break-up, Moddie returns to her hometown and her high school friends.

Her old friends are all professionals and academics so Moddie finds herself in the midst of a status competition. The protagonist can hold her own; she says what she thinks. She is funny but can be mean; the competition among her friends is an updated, grown-up version of the movie Mean Girls. The women, who are either married or with partners, are all unhappy. The men in the novel are asexual or, in Alan’s case, abusive. They are versions of the women in the HBO series Dystopia and, before that, the females in Lena Dunham’s Girls. They haven’t adjusted well to adulthood, their relationships are all dysfunctional, and they aren’t having much sex. The novel also matches up with the stats in a number of recent books about women in the post #metoo era. Marriage rates are down. There’s less sex. Successful women can’t find men. Too many men won’t grow up, preferring to hang back psychologically, to be incels, bros, and tech nerds. There is a growing political and emotional divide between women (who tend to be liberal) and right-wing men.

As the novel begins, Moddie tells us: “If she stayed with Nick, she … would continue to live this dead, boring life.” She tells us about her role in the relationship. “She did all the laundry, cooked all the meals, took out all the trash, cleaned, shopped, paid the bills, all of it…” Here is what Butler says about Nick: “He even talked to her in baby talk… he was always so very hungwy.” When Moddie returns to her hometown, walking on a college campus, “she stared in curiosity at the coeds, who laughed and screamed, blissfully unaware of what boredom and anguish were to come a mere decade later in their lives.” She doesn’t want to settle down and have kids: “Moddie rolled her eyes thinking again that mothers and children should be kept in a separate society until the child was at least 10.”

Butler is adept at cutting social commentary. After Moddie has returned to her hometown, she gets into a tense conversation with Kimberly about Facebook:

It’s the number one worldwide distributor of child pornography, but whatever helps you stay connected, I guess… Kimberly said that social media helped her stay politically engaged, and Moddie suggested that … the corporations that had encouraged everyone to adopt this idea that the websites were radical, so that the users could combine their petty addictions to the jolts of the mind-numbing dopamine of likes with the sanctimonious euphoria of imagining themselves as citizens and thinkers of the highest moral caliber, creating an airtight logic for everyone’s idiotic addiction to their smartphones, which were made with metals harvested by child slaves in factories with nets outside the windows to catch the suicides…

Novelist Halle Butler. Photo: Jerzy Rose

The climax of the novel is a sexual assault by Alan, the close friend of Moddie’s boyfriend. The physical attack is relentless. The guy, Alan, coerces his way into Moddie’s apartment, then swoops in on her. She says no over and over. He continues to grope and grab. She is drunk, eventually loses consciousness, and wakes to him on top of her. He will not stop no matter what she says or does. If you have not been sexually assaulted and wonder what it feels like, Butler’s graphic description brings the reader right into the woman’s point of view.

The chasm between how men and women view these events is illustrated by a conversation Moddie has with her boyfriend. Nick responds to her story this way: “They say that one in three women have been sexually assaulted, but if you talk to any guy, none of them knows a rapist.” In other words, Nick clearly sides with his friend Alan’s version of events.

Eventually Moddie comes to terms with the aggression and the break up and the novel lightens up. Although, oddly, supplying a happy ending is not one of Butler’s strengths. She’s best when she’s going negative. That may lead you to believe that the Banal Nightmare is depressing, but watching nasty characters be mean to each other, when the slicing-and-dicing is done with insight and wit, can be pretty entertaining (Balzac proved that). Why do you think Succession was so popular? Who would behave worst and who would lose the most? The characters in Butler’s terrific novel are not the unhappy super-rich of Succession, but they are white and privileged enough to be lampooned, in this case, memorably.

Ed Meek is the author of High Tide (poems) and Luck (short stories).