Book Review: The Rise and Fall of a Multivocal and Multicultural Alternative — “The Village Voice”

By Debra Cash

Looking back, the writing in The Village Voice was as good as Tricia Romano’s subjects remember. She excerpts paragraphs and the language is fresh, distinctive, sometimes profane, and always worth reading. For those who wrote books, it will send you back to the bookshelf.

The Freaks Came Out to Write: The Definitive History of the Village Voice, the Radical Paper that Changed American Culture by Tricia Romano, Public Affairs/Hachette, 571 pages, $35

Come for the gossip, stay for the slow-motion car crash that describes the decimation of the legacy newspaper industry. Tricia Romano, who spent eight years at the tail end of the life of the print edition of The Village Voice, apparently interviewed 200 people — good, bad and ugly — and then pieced together an episode-by-episode history in first-person recollections of the alternative New York paper that even some of its best friends referred to as a “commie, pinko fag rag.” The preface to The Freaks Came Out to Write supplies a helpful timeline of episodes in the life of The Village Voice, and most readers will need to refer to it because there are a lot of incidents, many speakers, and it’s hard to keep track of the changes at the paper from its legendary founding in the fall of 1955 through its death in 2018 and then shadow-of-its-former-self online revival in 2021.

Come for the gossip, stay for the slow-motion car crash that describes the decimation of the legacy newspaper industry. Tricia Romano, who spent eight years at the tail end of the life of the print edition of The Village Voice, apparently interviewed 200 people — good, bad and ugly — and then pieced together an episode-by-episode history in first-person recollections of the alternative New York paper that even some of its best friends referred to as a “commie, pinko fag rag.” The preface to The Freaks Came Out to Write supplies a helpful timeline of episodes in the life of The Village Voice, and most readers will need to refer to it because there are a lot of incidents, many speakers, and it’s hard to keep track of the changes at the paper from its legendary founding in the fall of 1955 through its death in 2018 and then shadow-of-its-former-self online revival in 2021.

The Voice was multivocal and multicultural. If it didn’t change American culture, its writers lived and memorialized a culture that no longer exists: one where an intrepid reporter could look at public corruption and not hedge his bets; one where the writers could scream at each other in the office and challenge each other outright on the page; where culture that wasn’t commercially remunerative was recognized as possibly even more important; one where the first person “I” was honored, because subjectivity was taken for granted and many writers were chosen specifically because they were a part of the scene — underground, fringe, emergent — that they were covering.

Voice arts writers were the early responders to trends in music, in visual art, in theater, in dance, and irreplaceable guides to the cultural valences that made up a community, whether that was gay culture before, during, and after the depths of the AIDS crisis, feminist critique, radical performance art, and the street culture that would become the parallel universe of commercial hip-hop.

It’s amazing to realize how randomly the talented Voice writers got their gigs. There’s a lot of “I wandered in” and “friends of friends” incidents: Hilton Als, for instance, got his job as an art department assistant because he went to high school with the sister of editor Lisa Jones. But given that no one ever wrote for the Voice for the money — there wasn’t much — the roll call of both the full-timers and freelance pool is astonishing. Writers deeply identified with the Voice for a significant number of years included Wayne Barrett (nemesis of a local real estate con man named Donald J. Trump), Jack Newfield (who ultimately carved a similar beat dissecting Rudy Giuliani), Nat Hentoff (civil libertarian/jazz writer), Ellen Willis (rock music and feminism), Stanley Crouch (culture writer), Robert Christgau (“the dean of rock critics”), Jules Feiffer (incomparable cartoonist), and Greg Tate (hip-hop and Black culture). Others did foundational work and then left, in huffs, layoffs, or poached by mainstream media. Still, even the people who left angry never forgot their Voice comrades.

Looking back, the writing was as good as Romano’s subjects remember. She excerpts paragraphs and the language is fresh, distinctive, sometimes profane, and always worth reading. For those who wrote books, it will send you back to the bookshelf.

The car crash comes not in the battle of personalities — although some of the ideological and personnel fights would have made a bystander want to hide under a paper-cluttered desk — but in a series of what, in retrospect, looks like doomed business machinations. The Voice was small enough, and its founding editorial leadership generally nimble enough, to carve out its own niche and stick to it, despite changes in ownership. The insider details about the outrage the staff felt over the sale of the paper to Australian press baron Rupert Murdoch in 1977, which led to the paper’s unionization, are particularly juicy. Even if you’ve never heard of Leonard Stern, the billionaire dog-food king who bought the paper from Murdoch in 1985, you have to appreciate that he was indeed a guy who “saw around corners” and realized, abruptly, that the Voice was heading toward collision with an iceberg.

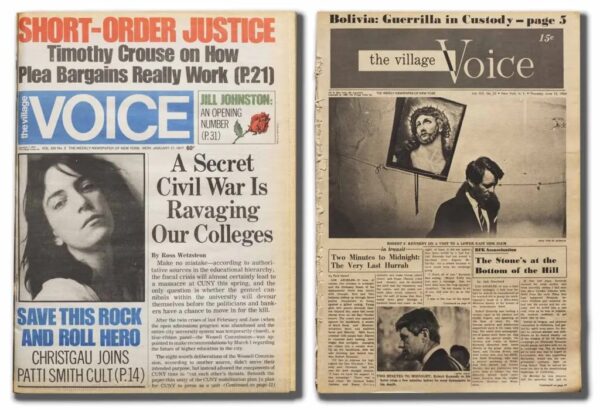

A couple of pages of the print edition of The Village Voice.

The iceberg was Craigslist. The Voice ran millions of lines of classifieds a year that generated half of the paper’s revenue. When Craigslist, with its free apartment listings and help-wanted ads, arrived in New York in 1996, “overnight a switch flipped.” There’s a great brief chapter where Romano interviews two programmers, Anil Dash and Akash Goyal, who were on the Voice’s digital team in 2000 and 2001. They tried to sound the alarm that digital disruption meant more than just replicating the paper online, but the pair couldn’t get much of a hearing. They’re also part of the discussion of how Google algorithms would come to replace curation. The trusting, mutually reinforcing community the Voice had fostered between its writers, subjects, and readers was becoming undone.

Reading The Freaks Came Out to Write, I had the insight that Substack, with its ultra-blogging, write-whatever-you-want, follow-your-favorite-writer and pay-what-you-will-or-not business model, may be the Voice’s contemporary heir.

But there won’t be any great parties.

Debra Cash, a founding Contributing Writer for the Arts Fuse and a member of its Board, wrote for both Boston alternative papers, The Boston Phoenix and The Real Paper, which overlapped with the Voice in many ways. She was interviewed by the Voice in 2000 and wrote one article for the Voice in 2002 when their regular critic was unavailable.

Totally great review.

Really nice piece.

Love your writing and loved this book