Book Review: “Real Toads, Imaginary Gardens” — Poems as Crime Scenes

By David Mehegan

Real Toads, Imaginary Gardens is a power-packed guide to the way poems are made and understood, a useful addition to the bookshelf of anyone who reads the art for pleasure.

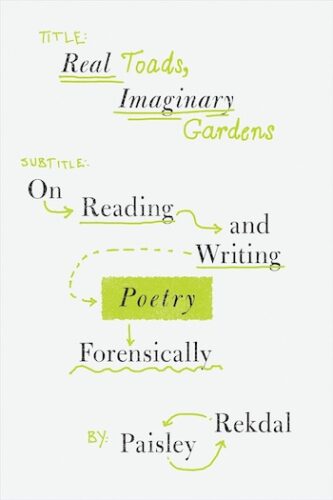

Real Toads, Imaginary Gardens: On Reading and Writing Poetry Forensically by Paisley Rekdal. W.W. Norton. Paper. $22.99. 304 pp

Poet and teacher Paisley Rekdal provides in this ambitious book an intricate grammar for reading and analyzing poetry in the conviction that it can make us better at both, if we try. Author of six collections and former poet laureate of Utah, Rekdal is distinguished professor of English at the University of Utah. Here in effect she admits us to her classroom or workshops.

Poet and teacher Paisley Rekdal provides in this ambitious book an intricate grammar for reading and analyzing poetry in the conviction that it can make us better at both, if we try. Author of six collections and former poet laureate of Utah, Rekdal is distinguished professor of English at the University of Utah. Here in effect she admits us to her classroom or workshops.

One might suppose that with “forensically” the author is associating the word with its venerable definition of rhetoric, here from the American Heritage Dictionary: “skill at using language persuasively and effectively,” as in discourse and argument in courts of law. Of course, a poet can use a word as she wishes. What Rekdal has in mind is the patient, accretive, step-by-step analysis of a poem that uses her “Forensic Guide,” a sort of method toolbox. She wants her readers “to treat any poem they encounter the way a detective might treat a crime scene: with a scientific interest in gathering evidence and material, to let these details reveal the scene’s narrative.”

“Crime scene” is an unexpected trope for a work of art, but then Rekdal uses the word “craft” more than “art.” The book “is a series of questions focused on craft: the craft of imagery; the craft of the sentence, the word, and the line; the craft of rhythm and sound; the craft of formal conventions and modes. By working your way through these questions of craft, you begin to see how a poem takes shape, how it accrues meaning through the intersection of these identifiable elements. … A poem is a ladder of skills, each of its elements carefully selected by a poet who employs their combinations for particular effects.” She means “questions” literally: each chapter title is a question: “What Images Are in the Poem?”, “What Kind of Lineation Does the Poet Employ?”, “Does the Poem Employ Meter?”

While the author does not say that all poets approach their art in this methodical, not to say consciously mechanistic, manner, it appears to be the way that she follows when she reads, dissects, teaches, and writes. The book is in large part a manual, a guide to teaching methods and tools, written, yes, for any intelligent nonprofessional reader of poetry, but perhaps more for active and budding teachers of poetry — practitioners of the craft, if you like. It even has a set of practice exercises (called “Experiments”) at the end of each chapter.

Her method is to employ one or more poems in each chapter and analyze them in terms of that chapter’s topic: lineation, diction, meter, syntax, imagery, mode, rhythm, etc. The poets employed include such marquee names as Alexander Pope, Sylvia Plath, Gerald Manley Hopkins, William Shakespeare, Robert Frost, Paul Celan, Octavio Paz, Elizabeth Bishop, and Robert Hayden. Many younger, not-well-known contemporary poets are included as well.

We encounter a wealth of precisely defined and explained terms, reprised at the end in a handy glossary. Besides addressing broad elements such as meter, rhyme, rhythm, and lineation, Rekdal covers the lexicon of metrical “feet”: the relationship in English verse of stressed and unstressed partial or whole words. So, for example, an iamb follows an “unstressed” syllable with a “stressed” one, as in “demand” or “attack.” A trochee (pronounced “TRO-key”) is the opposite, as in “feeling” or “hector.” An Anapest is a stressed syllable following two unstressed, as in “intervene.” A dactyl is two unstressed syllables following one stressed, as in “heavenly” or “evidence.”

More: Enjambment denotes a line that wraps around to the next to carry out the meaning, whereas “end-stopped lines” are just that: each ends with a complete thought (with or without actual punctuation). Deeper into the weeds we encounter epanalepsis, metonymy, distich, volta, envoi, hypotaxis, and synaeresis. Then there is metrical scansion, a code for how to actually mark stressed and unstressed syllables in a line of poetry. That would work in a magazine or photocopy, I guess, but I shan’t try it in my 1928 edition of Frost’s New Hampshire.

An elite mathematician once remarked that “one can enjoy the beauty and elegance of music without understanding its theory, but that’s not possible with mathematics.” Mathematics aside, I would say that the first part applies to all the arts: painting, sculpture, dance, theater, poetry, even architecture. Rekdal, I suspect, would not disagree. “There are as many ways to read and write a poem as there are types of poetry,” she writes, “And as each poem becomes its own unique expression of form and content, poems teach us how to read them as we read them.”

Poet Paisley Rekdal. Photo: John Barkiple

I do not doubt that there’s as much use in mastering the dictionary of poetry as that of classical music, with its intervals, temperaments, pitches, scales, tempi, colors, and harmonies. Yet, as the mathematician asserts, we can be transported by, say, the ravishing melodies in Rachmaninov’s C minor piano concerto (No. 2) without fluency in those terms.

To be sure, a composer needs to understand theme before she can write variations, and many of the wildest modern painters (Picasso, for one) began as students learning to draw the human figure. Nevertheless, often it is the encounter with the beautiful and the new that arrests our pleased attention. If there were no rule-breakers in poetry, none who jump the tracks and head off up a virgin hillside, nothing both new and beautiful would ever be written.

Rekdal writes that “for many people, reading poetry at all makes us squirm, and one reason for this is that we assume that poetry requires that we read it more deeply than other forms of literature: in other words, that reading poetry abandons pleasure and becomes work. This is largely due to the implicit belief that somehow poetry is meant to make us better people.” I doubt the prevalence of that belief, but I suspect it is true that if one masters the poetic lexicon in this book and uses it faithfully to analyze poems, as Rekdal does, it can be work, which for some will be pleasurable. Some people get pleasure from untangling a Rubik’s Cube.

Real Toads, Imaginary Gardens (the title is from a poem by Marianne Moore) is a power-packed guide to the way poems are made and understood, a useful addition to the bookshelf of anyone who reads the art for pleasure. That said, I must confess I found Rekdal’s prose to be heavy going in places. It could be that my forensic reading skills are deficient, or perhaps she’s more at home in poetry than in prose – her powerful 2019 collection, Nightingale, which I have read (without treating the poems as crime scenes), suggests as much. For that she can be forgiven; the obverse is true of many fine prose stylists.

Many times Rekdal makes firm assertions regarding the right or wrong answer in particular poems, as to “the point” of them or what they are (or are not) “about.” For example, writing of W.H. Auden’s “Musee des Beaux Arts,” which reflects on Pieter Breughel’s painting, “Landscape with the Fall of Icarus,” she claims that the poem “isn’t really about Breughel or arts but the particular distractions of the museum experience itself.” Notwithstanding that brisk reduction, we might keep in mind that a great poem can be about more than one thing, and to say this one “isn’t about Breughel or arts” strikes me as cavalier.

Much to her credit, Rekdal grants readers the right to dissent: “When it comes to poetry, I have to admit that definitive readings don’t exist, just as poetic rules themselves don’t finally exist. We work within patterns and limitations that we also defy.” Later she writes, “What makes a poem great is when the poet has metabolized and moved beyond [the] rules, creating another kind of form in which to confront experience.”

David Mehegan is the former Book Editor of the Boston Globe. He can be reached at djmehegan@comcast.net.