Film Review: “A Serious Man” Has Serious Thoughts

Reviewed by Justin Marble

Are filmmakers Joel and Ethan Coen becoming serious men?

For all of their acclaim, the Coen brothers have never been considered “personal” filmmakers. Technically talented, stylish, and humorous, sure, but in describing the Coens’ filmography, even their attempts at “mature” pieces deal in fantasy elements. Hitmen, large sums of money, and murder yarns proliferate the Coens’ oeuvre, and while these are not fantastic in a “Lord of the Rings” sense, they have little to do with the dealings of everyday life, and they only serve to obfuscate any glimpse into the Coens’ own thoughts and feelings. With the possible exception of “Barton Fink,” tracing more than a few elements of their films to their own experience proves difficult.

That all changes with their latest effort, “A Serious Man.” Instead, the film centers on a Jewish mathematics professor (like the Coens’ father) living in St. Louis Park, Minnesota, (the Coens’ hometown) in the late sixties (the Coens’ childhood). While all Coen films have an unmistakable style to them, “A Serious Man” is alone in its exact replication of a setting and characters from their own life,and that shows onscreen.

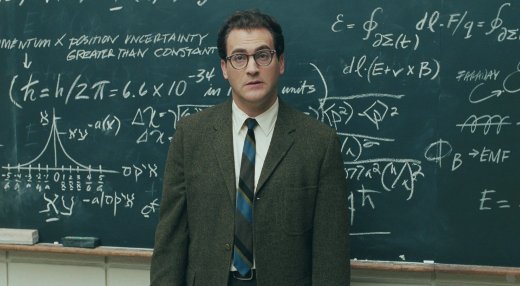

Michael Stuhlbarg plays Larry Gropnik, the previously-mentioned professor whose life isn’t going exactly to plan. His brother (Richard Kind) has moved into his house and shows no signs of getting a job, his son (Aaron Wolff) only speaks to him when he needs the TV antenna fixed, and his daughter (Jessica McManus) is at the teenage stage where she communicates exclusively in shrieks and huffs. Oh, and his wife (Sari Lennick) is shtupping (to borrow the Yiddish term) a man named Sy Abelman (Fred Melamed), which pretty much everybody feels is kosher because of what a “good guy” and “serious man” Sy is. As all this and more piles up and Larry’s life spirals out of control, he begins to question just what kind of God would allow all this to happen.

Yes, this is the Coens’ “religious” film, almost its own genre within film canon at this point. Man’s struggle with God is an area directors like Ingmar Bergman have explored frequently, but the Coens have never really given the issue more than a passing mention until now. And while “A Serious Man” extrapolates the core idea of religion into areas like politics and sexuality, there is no doubt that the backbone of this film is planted firmly in the Torah. The parallels to the Coens’ real-life upbringing only serve to suggest that the issues portrayed onscreen are still very much on their mind.

The Coens begin their film with a litmus test of sorts for the audience with a brief scene that is thematically but not structurally related to the rest of the film. Hundreds of years ago in a small Jewish village, a man and wife are entertaining an old man. The wife, being devoutly religious, begins to suspect that the man is a ghoul, back from the dead to terrorize and possibly harm her family. Whether one believes her actions are noble when she stabs the man hinges on a personal belief in God. This act can be seen as heroic, defending herself from the demon’s machinations, or needlessly murderous. For the Coens, morality is inextricably linked to one’s own spirituality.

This is a theme that pops up often in “A Serious Man,” where Larry grapples with these very issues, albeit in a different way. Stuhlbarg plays Larry with a sense of earnestness, such that he comes off as a sympathetic character who is truly trying to do good. But his dwindling belief in God blurs the lines as to what “good” actually is.

Sy Abelman is considered by all to be “good,” and he has an affair with Larry’s wife. So can Larry have sex with his hot neighbor guilt free? A Korean student of Larry’s offers him a bribe to give him a passing grade. With many worthy causes in Larry’s life in need of cash, including his poor, tumor-afflicted, unemployed brother, is there really much harm in changing that F to a D-, especially if it goes toward a worthy cause? What is a worthy cause? And is Larry truly afraid of God, or the slightly more immediate tenure board?

Michael Stuhlbarg plays Larry Gropnik, a professor whose life isn’t going exactly to plan.

To their credit, the Coens dig surprisingly deep into thorny issues with their film, and they don’t lose their ability to inject bleak, dark humor at every turn. They also give the sense that these are issues that they are trying to work out as well, but that doesn’t mean they leave things ambiguous. Their contempt for organized religion is clear here in the Coens’ portrayal of three local Rabbis as blathering fools, who use circular logic and misdirection to defuse even the slightest questioning of God’s will. The Coens posit that despite their supposed “wisdom,” these men of the cloth do not have any more knowledge of these things than the rest of us.

“A Serious Man” is not without its stumbles. There are many scenes and moments in the film that probably mean something to Joel and Ethan alone, and the audience is left in the dark. Specifically, the mentioning of Larry’s brother’s “mentaculus,” a mathematical proof that is supposed to lay out the probabilities of the universe, is left unexplained and untied to the rest of the film. The segments of the movie dealing with Larry’s son getting high while studying for his Bar Mitzvah, while funny and probably ripped straight from the Coens’ lives, detract from the more high-minded ideas at work And the Coens’ philosophical ponderings, while valid, are nothing new or groundbreaking.

Yet it is the first time in perhaps their whole career where one can see that the Coens have made a film that truly means something to them. They are not engaging in playful genre games (“Fargo”), amusing yet pointless farces (“Burn After Reading”), or translating somebody else’s thoughts to screen (“No Country for Old Men”). No, the thoughts behind “A Serious Man” are their own, and they don’t hide behind A-list celebrities in delivering those thoughts to a mass audience. Perhaps this is a flash-in-the-pan, and the Coens have not really matured as filmmakers. Then again, maybe this is just their first step in finally becoming “serious men.”

Tagged: A Serious Man, Coen Brothers, Ethan and Joel Coen, Jewish, Justin Marble