Poetry Review: “What Comes from the Night” — Witnessing Tiny Secret Lives

By Clara Burghelea

What Comes from the Night testifies to John Taylor’s complex bond with nature, a generous alliance that includes moments of introspection and melancholy.

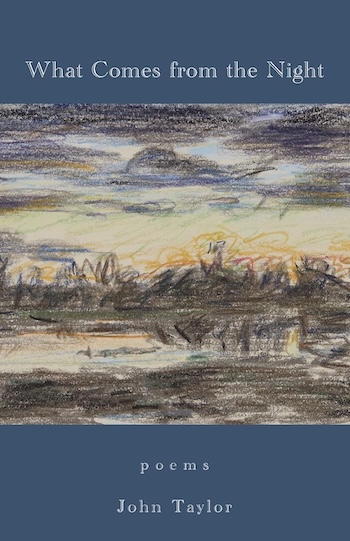

What Comes from the Night by John Taylor. Coyote Arts, pp 124.

John Taylor is the author of several volumes of short prose and poetry, most recently 2018’s Remembrance of Water & Twenty-Five Trees (The Bitter Oleander Press). He is also a polyglot literary critic whose essays fill five volumes (Transaction Publishers) — three devoted to French literature and two concentrating on European poetry. Fluent in French, Italian, and Modern Greek, Taylor’s most recent translations of poetry include Veroniki Dalakoura’s Bird Shadows (Diálogos Books), Charline Lambert’s Of Desire and Decarceration (Diálogos Books), and Franca Mancinelli’s All the Eyes that I Have Opened (Black Square Editions).

Taylor latest collection of his verse, What Comes from the Night, contains nine sequences and two independent poems. In terms of location, the assemblage invites the reader to explore a rural, pastoral, sometimes Alpine landscape. This is a poet who pays nuanced tribute to the seasons, focusing on nature’s bounties in ways that successfully engage the speaker’s senses and emotions. The poems dramatize a quest: the observer is looking to find himself and his place in the vastness of nature:

in front of the stone well

you cast an arc

with your flashlight

you are searching for something

you have dropped inside

yet grope for it

within a memory of light

The first sequence, “Endings and Beginnings,” addresses an imaginary “you,” a figure who is both self-aware and self-effacing. The verse closely examines the natural world, hunting for inspiration:

a dark golden flare, a word

swims up, dives

to where it must go

you must go

a dark golden flare

you can begin writing these poems

The sensibility that guides the next poem, “Sandbar,” zooms in on the movement of a river. This sequence prepares the reader for what follows, “Seascape”. During the latter, the speaker is in a nebulous psychological state — both grounded and floating:

again an island

where you bedded bones

on granite

*

the clouds reply

with their journey

no why stops them

Enjambment is used to illustrate the movement from earth to sky, intimations of melancholy gently nurtured from one line to the next. Particularly effective: how the alliteration of “bedded bones” slyly underlines the poem’s terse, but graceful, musicality.

Other poems in the collection draw attention to the speaker’s growing awareness that he is part of a universal design:

silence that is no longer sleep

nor the width of the ocean

the continent between

perhaps what you heard

during all those centuries

indeed try to remember

what you listened to

for millennia

before you were born

Taylor’s poems are filled with a linguistic playfulness, particularly a skillful use of enjambment and alliteration, that infuse an appealing musicality to his lines. The word-driven energy of the speaker is alert to the potentiality of nature, its abundance. For example, “Yellow Wildflowers” presents the portraits of nineteen yellow wildflowers found and identified in France, in some cases located in the Franco-Italian Alpine Garden on Mount Cenis. (Taylor provides the common French and Italian names of the flowers in the notes at the end of the collection.) The nameless (sine nomine) / sans nom/ senza nome wildflower is the final entry in the suite:

you are the nameless flower

of coincidence:

a shadow lingers,

the path turns,

and you gleam

Taylor’s sensitive eye never loses sight of his surroundings, the beauty and strength of water and wind, the scintillating touch of light, sand, rivers, vegetation. On the one hand, these are poems by an observer who is overcome by wonderful things — including the passage of time and our longing to belong. Yet the title poem, “What Comes from the Night”, suggests that nature activates the speaker’s curiosity: “when the real wind blows / through leaves your answers / branch into questions”. The metaphor evokes the poetic force of curiosity. The same branches reappear a few pages later, and they transform from questions into shelter: “all the dead branches stacked up / to make a lean-to / under which you’d like to crouch”.

The poet’s meditations summon the reader to acknowledge the “tiny secret lives” of things and to embrace their mystery:

and from woods

from a clearing

your dream slips off

between tree trunks

faint birdcalls trails

narrowing

to tiny secret lives

The almost Tennysonian presentation of this idyllic natural world is infused with the poet’s interrogatory spirit: “after the storm you rake / the autumn; / between the last leaves / the grass glistens”. The speaker in this poem not only embraces the mutability of nature and seasons, but the tentativeness of his own being: “a mere root / in your days, / you are warmed / and surface.” Taylor’s poems infuse a visceral power into everyday interactions with nature: “wet birch leaves / on the ground: dance steps / in next realm”. Taylor engages the senses, but he is also contemplative; he activates the imagination through his reinvigoration of familiar concepts: “as when in childhood you spotted / a rabbit through the hedge / that separated two worlds”. The artful meditativeness of Taylor’s work, along with its sonic rhythmicity, is what makes it such a pleasure to read. What Comes from the Night testifies to Taylor’s complex bond with nature, a generous alliance that includes moments of introspection and melancholy.

Clara Burghelea published two poetry collections: The Flavor of the Other (Dos Madres Press 2020) and Praise the Unburied (Chaffinch Press 2021). Her poems and translations have been published in Gulf Coast Journal, Delos, The Los Angeles Review, and elsewhere. She is the Review Editor of Ezra, An Online Journal of Translation.