Book Review: “The Propagandist” — The Power of Flawed Memory

By Ori Z Soltes

Cecile Desprairies’ extraordinary work is a cross between the dispassionate inquiry of a historian and a family memoir whose author is searching for catharsis at the end of her attempt to understand her family’s place in the Nazi-collaborationist narrative.

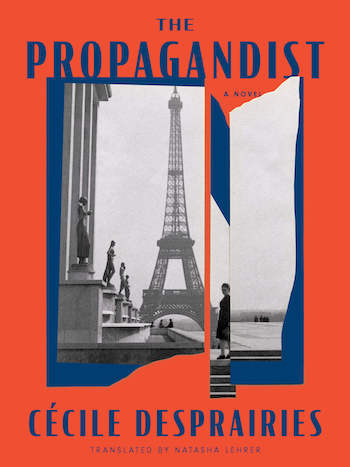

The Propagandist by Cécile Desprairies. Translated from the French by Natasha Lehrer. New Vessel Press, 208 pages, $17.95

In the first chapter of his last book, The Drowned and the Saved, Primo Levi writes about memory as a magnificent but defective human instrument. He quickly focuses his lens on the ways and reasons in which memory’s flaws are used by perpetrators and victims of extreme traumas to alter the narratives of their pasts. The context, of course, in which he offers this discussion is the Holocaust and its aftermath. In the case of victims, he articulates what he calls a “grey zone” between the black and white of guilt and innocence: the physical survivor rarely fully survives emotionally and psychologically, assailed for years by the shame of still being alive when “better” people are not.

In the first chapter of his last book, The Drowned and the Saved, Primo Levi writes about memory as a magnificent but defective human instrument. He quickly focuses his lens on the ways and reasons in which memory’s flaws are used by perpetrators and victims of extreme traumas to alter the narratives of their pasts. The context, of course, in which he offers this discussion is the Holocaust and its aftermath. In the case of victims, he articulates what he calls a “grey zone” between the black and white of guilt and innocence: the physical survivor rarely fully survives emotionally and psychologically, assailed for years by the shame of still being alive when “better” people are not.

In the case of the perpetrators, he notes not only the iniquitous (his term) imbalance between the post-trauma discomfort that those who created the trauma may feel, and their victims, who were caught by it. He also provides evidence that perpetrators will admit feeling shame, guilt, or own up to the responsibility of having participated in and/or perpetuated the horrors visited upon their victims. But there is a catch: perpetrators not only deny and contrive untruths about what they did and who they were, but in many cases arrive at a point, through constant reiteration of false narratives, of believing in their own innocence.

This Levian discussion offers an eloquent framework for Cecile Desprairies’ extraordinary work — a cross between the dispassionate inquiry of a historian and a family memoir whose author is searching for catharsis at the end of her attempt to understand her family’s place in the Nazi-collaborationist narrative. The central protagonist is Lucie — the mother of the writer, a rather brilliant lawyer and biologist. Desprairies’ central purpose is both to recover the lost, altered narrative of what her mother’s role was in the intrusion of the Holocaust into the French collaborationist and resistance world of World War II, and to come to some understanding of her larger family as well as significant parts of her own early childhood. The Propagandist grapples with the profoundly skewed memory, as offered by Lucie and her family, of that world.

This is a memoir that also reads, in part, like fiction. While it features Levi-like analytical discussion, The Propagandist also feels like a novel, its imaginative power resonating with the works of Balzac, Tolstoy, Mann, and Proust — particularly the last of these — writers who offer very rich and psychologically acute descriptions of the interactions of extended families at particular times and over time.

If Desprairies’ work had ended after the first chapter — or simply continued along the same line — it would have been a charming and slightly comedic slice of French life about a particular socio-economic class and/or socio-ethnic group and its place (or struggle to weave the threads of its place) within the French socio-economic-political fabric at large. It is a delightful portrait of her eccentric mother and the circle of family females of which she is the center. The author views them as performers in an ongoing drama (she uses the phrase, commedia dell’arte, at one point, to suggest the kind of domestic farce she is witnessing) for which she herself, as the small, silent child who is presumed not to understand what is going on — and to a large extent does not, and will not, until much later — is the essential, drama-completing audience.

Cécile Desprairies. Photo: Wiki Common

Already, however, late in the chapter, there are hints of something darker beneath that quasi-comedic surface. There is a passing reference to the Holocaust and the destruction of Jews, and then a reference to the infamous (to those who know about the French and the Holocaust) Velodrome d’Hiver into which so many French Jews were herded in summer, 1942; and later a brief discussion of Uncle Gaston and his wartime associations. These references are the novelistic foreshadowings of the issues explored in the rest of the volume.

The opening lines of the second chapter — beginning: “[i]n the winter of 1940, at a party in Paris for medical students, Lucie met a man called Friedrich. She had just turned twenty-one; he was twenty-four” — sets the rest of the story in motion. Friedrich is an Alsatian German — “his parents chose France. For him, to align oneself with France was to align oneself with the losing side” — a devoted Nazi whose passion for a particular kind of medical studies (genetic biology and eugenics) would surely have put the fascist in the direction of a Josef Mengele-like career had circumstances been slightly different. He preferred not to waste time being a soldier — not, of course, out of cowardice, mind you, but because he recognized the importance of his role as a scientist shaping the future. And for Lucie — who, it turns out, was an equally fervent Nazi, both in her own right and as his acolyte — he became the absolute love of her life.

This important datum, embedded within other data pertaining to family members and their what-and-where activities during the War, cascades through the rest of The Propagandist. Desprairies endeavors to dovetail a comprehension of Lucie’s political and ideological beliefs with her own coming of age, which is rooted in her attempt to properly grasp her family legacy.

Helpful information will trickle out, but while Friedrich was her mother’s true love, he perished before their union could produce substantive consequences. Only passionate memories. The references to his death offer a Levian exercise in altered memory — or, rather, constantly shifting memory. We never clearly learn what happened to him: that he was executed as a Nazi by resistance forces as the war was winding down to a conclusion. The Nazis were defeated and (theoretically) expunged from France, which had its own deep, dark participation in the anti-Jewish proclivities of Nazism. More to the point: the author’s father, Charles, was a kind of second husband — of convenience, one might say — who provided both a stable socio-economic structure and children for Lucie. And he accepted — almost (almost) seemed to embrace — the lifelong emotional menage-a-trois that kept Friedrich (and his oft-visited gravesite) at the center of the family over the decades.

The original psychological menage-a-trois, to which Desprairies’ father eventually became the fourth character, included a barely repressed gay Nazi-adoring Benedictine monk who was as obsessed with Friedrich as Lucie was. The cleric dined for years at the family table, becoming a kind of ideological stand-in for Friedrich after the latter’s death. This fascinating array offers an oblique echo of the first chapter’s domestic line-up of women. The multiple resonances deepen Desprairies’ narrative, as she wrestles with the ghosts that define her identity as a daughter in her quest to understand both her family and her mother. It is this fusion of memory and research — in which the personal and the political are deeply entangled — that makes The Propagandist stand out from the growing library of works focused on the Nazi era.

Much of what Desprairie has to grapple with is the nihilistic allure of fascist political fantasy which extends through the war years and for decades beyond the war and the success and defeat of Nazism. The dreams range from specific hopes of an autonomous Nazi-governed Burgundian state and Lucie’s brilliantly successful work as a propagandist (the Germans called her die Propagandistin) for the regime in France to casual references to the massacre of Jews as, simply, comme il faut in a more perfect world. Friedrich, Lucie, and the Benedictine monk were all dedicated to “the total transformation of France. The actions of the National Socialists were moral because they were political. Any blunders the Nazis made were not crimes… they were always necessary. It was vital to rise above such concerns… Their mission in life was messianic…”

The author begins to grasp all of this as she traces the path of her mother’s literary and personal focus (notably the above-mentioned Proust, ironically enough, a Jew; and Celine — both artistic icon and personal friend). Lucie was a public PR-master as well as a private master-shaper of the family fortunes in the post-Nazi era, with the dangers it posed to former Nazis. And it is that difficult legacy her youngest daughter is desperate to unravel and explain — and to bequeath to us, her readers, who cannot but be mesmerized by this winding tale of those so emblematic of that long human condition of being both drowned and saved by time and flawed memory.

Ori Z Soltes teaches in the Center for Jewish Civilization at Georgetown University. He is co-founding director of the Holocaust Art Restitution Project in Washington, DC.