Short Fuse Commentary/Review: A Social Problem

I feel like such a nag, but someone ought to be able to point out a 300 lb gorilla in the room when it knuckle walks, glowers and pounds the walls. I will be that very nag and shortly name the ape accordingly.

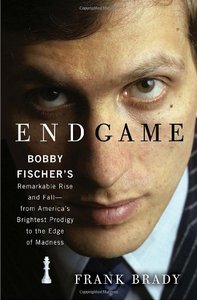

Endgame: Bobby Fischer’s Remarkable Rise and Fall—from America’s Brightest Prodigy to the Edge of Madness by Frank Brady. Crown, 416 pages, $25.99.

By Harvey Blume.

(Read The Arts Fuse review of the Sundance hit, Bobby Fischer Against the World)

It was already obvious when he was a very young boy that he suffered from a “social problem”. He “couldn’t relate to other children”—to the tune, for example, of getting kicked out of kindergarten. His biographer, as is his wont, puts the matter more softly, writing that Regina, the boy’s mother, “was compelled to withdraw him.” He adds that the kid “invariably separated himself from other children [and that] by the time he reached the fourth grade, he’d been in and out of six schools—almost two a year—leaving each time because he couldn’t abide his teachers, classmates, or even the school’s location.”

It takes an inordinately touchy kind of little kid to throw a fit on account of a school’s location. But this was an inordinately touchy kid, full of tantrums, primed for fits. This was a kid who fell to “ranting if he didn’t get his way” about food, bedtime, and other details of his regimen. Such behavior did not decrease as he matured. Details of light, sound, and texture that most people would barely register weighed on him. Variations in routine could set him off.

Regina raised this boy and Joan, his older sister, on her own. The argument can be made that Regina’s commitment to various and sundry leftwing causes got in the way of maternal responsibility. It can just as plausibly be maintained that Regina was nothing less than the stereotypically devoted Jewish mother. Having gleaned, or hoped for, some spark of brilliance to set alongside her son’s intractability, she managed to enroll him in a school for gifted children. He lasted for a day, making it clear he would never, on any account, go back.

The setting is Brooklyn in the 1950s—well before Oliver Sacks, SSRIs, or, more to the point, any “Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders” (DSM) could even roughly describe this boy’s behaviors. There wasn’t any appropriate understanding for his syndrome and next to no remediation for it.

The one thing that seemed to settle the boy down and fully absorb his stormy energies was puzzles. They could engage him for hours, granting Regina and Joan respite. When her brother was seven, Joan happened to bring back a cheap chess set: plastic pieces, cardboard checkerboard, the kind of thing you’d get for a quarter at the candy store. Joan, reading the rules that came with, taught her brother to play.

He mastered that puzzle system so well that people now puzzle over him.

***

For Gary Kasparov, Bobby Fischer was a kind of centaur, a human player mythologically combined with the very essence of chess itself.

The kid is of course Bobby Fischer. The biographer is Frank Brady, author of Endgame: Bobby Fischer’s Remarkable Rise and Fall—from America’s Brightest Prodigy to the Edge of Madness. The gorilla in the room is Asperger’s Syndrome. Let us, for now, leave that ape on a tottering, Brooklyn kitchen table and focus first on several of the considerable virtues of Brady’s astoundingly gorilla-blind account.

Brady does a fine job portraying the New York City chess scene as Fischer came to know it in his teens—Washington Square Park’s outdoor summer tournaments; the Manhattan Chess Club “decorated with trophies [and] oil paintings of legendary players such as Lasker, Morphy, and Capablanca”; the impressions and depressions left by Soviet champions who passed through town from time to time to crush America’s best talents like so many dark lords, incidentally making the point that Communism built better brains.

Brady is capacious and leaves ample room for serendipity. We learn, for example, that Marcel Duchamp, who lived across the street from the Marshall Chess Club in Greenwich Village, “became a great fan of Bobby’s.” It is fascinating to think of what encounters between Duchamp, an accomplished chess player in his own right (member of the French national team in 1932, for example), and Bobby Fischer might have been like. A friend of his once remarked that Duchamp often needed “a good chess game like a baby needs a bottle.” How sympathetic, then, Duchamp, in his sixties, would have been to the teenaged Fischer’s boundless appetite for chess—for openings, endgames, tactics, strategy, lore, and, above all, the matches themselves.

Duchamp had once opined that to his mind, “all chess players are artists.” Perhaps, as Bobby compiled his wins—including one when he was 13 against an ex-US champion still celebrated and studied as the “The Game of the Century”—Duchamp felt that he was witnessing the likes of a young da Vinci, not on that shopworn medium, the canvas, slave to the retina that it was, but in an arena better suited for conceptual interplay and interaction, the chess board.

It is also to Brady’s credit that he corrects an enduring misconception about Fischer. Yes, in his youth Fischer only read about chess, scrabbling up enough Russian, for example, to absorb Soviet chess journals. Brady establishes that in his later years, Fischer became a voracious autodidact. He does not fail to point out that Fischer’s consumption of history and philosophy oddly did nothing to soften his rabid and ridiculous—Fischer himself being Jewish—anti-Semitism or to counteract the grotesque anti-Americanism that led him, after 9/11, to praise al Qaeda.

Though it does not excuse him, it needs to be said that Fischer had a kernel of reason for anti-Americanism. The United States treated him just as it does so many tyrants—Ferdinand Marcos, Saddam Hussein, Muammar Qaddafi, to name a few. They are coddled when they are useful and obedient, dismissed when they no longer serve. Fischer, a self-made autocrat of chess, refused to heel.

In 1972 it wasn’t clear if Fischer would show up in Reykjavik to play Boris Spassky for the world championship or fall prey instead to the tantrums roiling within. Tantrums seemed to have the upper hand. That was when Secretary of State Henry Kissinger called and told Fischer it mattered beyond chess; it mattered to the free world; Fischer must play. Fischer flew to Iceland and famously demolished Spassky.

Twenty years later, Fischer came out of self-imposed retirement to play Spassky again. Matters of state had no part in it; the then penurious Fischer needed money. The match was set for Yugoslavia, in the midst of a civil war that subjected it to U.N. sanctions. This time Fischer was ordered by the State Department not to play—on pain of fines and imprisonment on return to the United States. Where was Kissinger, now, when Bobby needed him? Fischer did not like being a pawn in that political match. Chess was his only game. At a press conference, he held up and literally spat on the order to desist.

**

Why call that 300 lb gorilla by its proper name? If it needs to be named at all, why not just call it Anonymous Gorilla and let it go at that? The reason to name it Asperger’s Syndrome is that it lends coherence to Bobby Fischer: the root, childhood anti-sociability, the tantrums, the acute susceptibility to sensory experience—the overwrought sensorium Temple Grandin, among others, has so well described—as, for example, his violent reaction to the whirring of cameras in his first match against Spassky.

Then, of course, there is, above all, his savant grasp of chess.

It does not dehumanize Fischer to take seriously the prospect that he had Asperger’s Syndrome. On the contrary, it humanizes him; it makes *him* less of a 300 lb gorilla. You don’t have to have Asperger’s Syndrome to excel at chess. Lots of mentalities—of neurological styles, as it were—compete on equal terms in that game. But it is somewhat absurd to not to entertain the possibility that Fischer came to chess with the configuration of gifts and deficits particular to the autistic spectrum.

No, Bobby Fischer is not to be confused with Raymond Babbitt, the low functioning, institutionalized, autistic man played by Dustin Hoffman in Rain Man. Fischer occupies a very different place on the autistic spectrum. He was independent, successful, and renowned—already a celebrity while attending Erasmus Hall High School in Brooklyn. But it doesn’t detract from Fischer’s achievement to think for a bit about Raymond Babbitt’s uncanny ability to count cards in a blackjack game or to size up almost instantly how many toothpicks spill to the floor from a full box.

Even the best of Fischer’s peers would sometimes allow that he seemed to have a privileged access to chess. That sense of Fischer as rather more than the first among equals was palpable in the reaction to his victories in the candidate matches leading up to the historic 1972 bout with Spassky. In one he beat Mark Taimanov, his wizened Soviet opponent, 6-0. To win a match without a single loss against world class opposition was unprecedented. Fischer compounded that victory by shutting out the great grandmaster Brent Larsen next.

The Soviets took their chess seriously and regarded the approach of the American chess comet with apprehension and astonishment. Brady writes of Fischer v. Larsen that “Television and radio networks throughout the Soviet Union interrupted regular broadcasts to announce the results. Millions of Soviets were avidly following the progress of the match, fascinated by Fischer’s supernormal mastery. Sovietsky Sport declared, ‘A miracle has occurred.'”

To propose that Fischer had Asperger’s Syndrome does not imply the search for language to describe him can be aborted. It is hard to improve on a comment by Garry Kasparov, who, after Fischer died in 2008, said that he thought of Fischer “as a kind of centaur, a human player mythologically combined with the very essence of chess itself.” Chess has always occasioned great literature—novels by Vladimir Nabokov, Paul Zweig, and Walter Tevis, to name a few. But never has a living chess player spurred writers on as Fischer did.

Robert Lowell wrote a poem, “The Winner,” consisting entirely of Fischer quotes. It opens with these lines, all Fischer’s:

I had the talent before I played the game;

I made the black moves, then the white moves,

I just muled through whole matches with myself —

it wasn’t too social only mating myself. . .

Arthur Koestler, in “The Glorious and Bloody Game,” his dispatch from the Reykjavik match, was driven to conceive a whole new species in order to properly characterize Fischer. He came up with the idea of the mimophant—”a cross between a mimosa and an elephant.” The mimophant, he explained, was “like a mimosa where his own feelings are concerned and thick skinned like an elephant trampling over the feelings of others. . . . Bobby is the perfect representative of the species. His vulnerability is genuine. The cameras do upset him. He cannot bear street noises. The chair on which he sits while playing, the size of the board grate on his mimosaesque sensitivities. At the same time his elephantine skin prevents him from realizing what he does to others.”

Koestler might have added that Fischer’s elephantine skin could not protect his mimosaesque sensitivities from the kinds of injuries he inflicted upon himself.

***

The last photo known of Bobby Fischer shows him in a Reykjavik coffeehouse, not long before he died of renal failure, having—dictatorial as ever about his regimen—refused medical treatments that might have helped. There is a penetrating intensity to his expression. This is not the look of a man who feels defeated. Perhaps it is the look of a man who has the courage to bear defeat. There is depth and ferocity to the expression. I grew up in Brooklyn a few years after Fischer. I played some chess. He was something of a hero to me then and despite the horrific flaws—the strident destructiveness and self-destructiveness that manifest over time—he still is. And as for these flaws, it puts things in perspective to note that his anti-Americanism recruited no one to al Qaeda, nor did his anti-Semitism reanimate any Nazi party. He was always the chief victim of his warped worldview—and beside him, chess.

In that photo he is sitting in front of a wall hanging portraying games—a miniature chess board and something that looks like Icelandic scrabble. No one could have known when this picture was taken that it would be the last. Luck plays its part in showing him peering out from the games, puzzles, and chess boards that were his soil, his beginnings.

Tagged: Asperger's Syndrome, Bobby-Fischer, Endgame: Bobby Fischer's Remarkable Rise and Fall, Frank Brady, chess