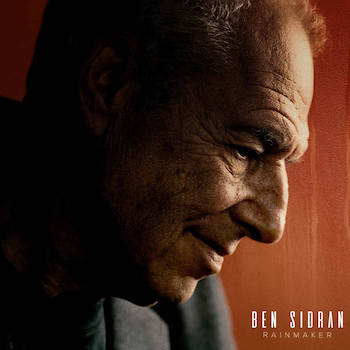

Musician Interview: Veteran Vocalist/Pianist Ben Sidran on Expanding the Aural Horizon in “Rainmaker”

By Steve Provizer

“Popular music in America is already so formulated and dumbed-down that the fear of AI making it more trivial is probably beside the point.”

Rainmaker personnel: Ben Sidran, vocals, piano, and organ; Leo Sidran, drums; Billy Peterson, vocals; Max Darmon, bass; Rick Margitza, John Ellis, sax; Romain Broussouliere, guitar; Olivier Ker Ourio, harmonica; Andy Narell, steel drums; Denis Benarrosh, percussion; Rodolph Burfger, guitar, vocals; Camille Marotte, background vocals, and Mike Mainieri, vibes.

Ben Sidran inhabits a sparsely populated section of the jazz world. He plays keyboards, sings, writes music and words. He’s produced records for Mose Allison, Van Morrison, Rickie Lee Jones, Diana Ross and Steve Miller (with whom he also played and co-wrote “Space Cowboy”). He has hosted jazz shows on VH1 and NPR and released 60 of his NPR interviews in a 24-CD box set called Talking Jazz. Not done yet. He’s also the author of several books, including Black Talk, There Was a Fire: Jews, Music and the American Dream, and The Ballad of Tommy LiPuma. For a quick dose of Sidran’s insight and subtly erudite style, read his essay on artist Stuart Davis.

Ben Sidran inhabits a sparsely populated section of the jazz world. He plays keyboards, sings, writes music and words. He’s produced records for Mose Allison, Van Morrison, Rickie Lee Jones, Diana Ross and Steve Miller (with whom he also played and co-wrote “Space Cowboy”). He has hosted jazz shows on VH1 and NPR and released 60 of his NPR interviews in a 24-CD box set called Talking Jazz. Not done yet. He’s also the author of several books, including Black Talk, There Was a Fire: Jews, Music and the American Dream, and The Ballad of Tommy LiPuma. For a quick dose of Sidran’s insight and subtly erudite style, read his essay on artist Stuart Davis.

Sidran’s style of composing, singing, and piano playing can put one in mind of Mose Allison, Bob Dorough, and Dave Frischberg. Like them, his voice is serviceable — expressive rather than sonically impressive. The piano playing of this group shows technical competence, rooted in blues and bop. As lyricists, they all cover their own territory, from drolly countrified to archly urban. Sidran’s lyrics are closest to those of Allison, but with a more metropolitan quality. Sidran’s music tends a little more often to the funky side of jazz.

Sidran’s recent release Rainmaker was recorded in Paris and covers a lot of bases. There are several blues: “Rainmaker,” “Times Getting Tougher” and “Someday Baby” (heavily gospel-inflected). “Victime de la Mode” (Victim of Fashion) is a funky-rap-pop tune; the album notes say that French rapper MC Solaar’s 1991 hit “Victime de la mode” used a two bar sample of Sidran’s “Hey Hey Baby.” Sidran’s new lyric tells that story and so layers are built on layers. There’s a nice Island-Latin-Funk tune “Panda,” with adept steel drum and harmonica solos. “Sosi B” is an upbeat funky Herbie Mann-ish tune with good tenor sax and trumpet solos, and “So Long” is a straight-ahead love song with Mike Mainieri on vibes.

Several songs are more introspective. In fact, the album notes inform us that “he began with a small collection of songs that he referred to as his ‘dystopian suite.’” Songs like “Are We There Yet,” and “Humanity” evoked an eerily haunting rendering of 21st century life.” We talked about some of the tunes and covered a wide range of subjects in this interview, conducted by email.

Arts Fuse: Rainmaker was recorded in Paris. Is the studio recording experience different than it is in the US?

Ben Sidran: Studios in Europe often have different microphones and they have their own technique for setting them up — they like more room sound, whereas in the States one is more inclined to close-mic an instrument. And the lunches in Paris studios are way better and more relaxed than anything in the States. But generally speaking it’s not that different.

AF: On “Humanity” a French voice (Rodolph Burger) shadows your English lyric in French. And on “Are We There Yet,” he shadows it in English. Can you explain why you made this a part of these songs?

Sidran: I use Rodolph’s voice partly as a way to expand the aural horizon — just as his guitar sound creates atmospheric depth — and partly for the back and forth of language. When I’m listening to people speaking a language I don’t understand, it’s a good approximation of my experience with music. There’s music in the words and there’s more meaning in the music.

AF: Jazz musicians have been traveling to Europe for over 100 years. It’s a truism that Black musicians found a friendlier racial climate. Have you found traveling there different than when you first went over in the 1960s? Is there a difference in how your music is received?

Sidran: I have not noticed that much of a difference in the way my music is received in Europe. I’ve been playing there for 50 years and I’ve always had a good audience. However, the scene is very different, since so many young European musicians are playing out; much more competition, which is good. It forces one to focus on style more than technique.

In general, jazz musicians are more disposable in America than in Europe. In Europe they are protected as any worker is protected and their place in society is respected. So, another difference is that there are many more young and very skilled players all over Europe. But overall, the biggest difference in Europe today and Europe 60 years ago is simply the number of tourists. The streets are crowded by “an invasive species.”

Ben Sidran — he inhabits a sparsely populated section of the jazz world.

AF: There are some serious lyrics on this album: “where did we lose our humanity, where did we go astray…” “the systems were failing…” “people are becoming possessed by their tiny screens…” Give us a sense of the state of mind that brought you to these thoughts.

Sidran: Today we are all experiencing a kind of mass PTSD. Not just in America, where we are reeling from the Trump years and the parallel rise in intolerance, but everywhere on the planet — rising nationalism, deteriorating ecologies, pandemics, and institutional greed. If there is a kind of dystopian urgency to some of the lyrics, I can accept that.

AF: Not to be arch, but spending time out of the US political scene probably helps you to retain some optimism. Despite some of the more dire lyrics, you seem to see a possibility for a ray of light to break through the gloom. For example, you choose to do “Ever Since the World Ended,” a Mose Allison song that you originally produced for him in 1987. The tune is largely downbeat, but the last chorus turns things around completely: “Ever since the world ended, there’s no more black or white. Ever since we all got blended, no more reason to fuss and fight.”

Sidran: Humor is the answer; what’s the problem? Humor is the best way to encode how you really feel and it’s something that Mose Allison always employed to get his point across. I never thought of Mose as downbeat; I always thought he was the antidote to cynicism. His humor saves the day and, in general, I believe that if you can’t laugh at life you’re through. Having said that, these are some hard times and we have to call it what it is.

AF: We find AI already having an effect on the income of musicians. How do you see AI affecting the future of music?

Sidran: Popular music in America is already so formulated and dumbed-down that the fear of AI making it more trivial is probably beside the point. As far as most working musicians getting paid in a world of AI, I think it’s going to get tougher — a bad situation getting worse. The big fish are getting bigger and the small fish are getting eaten. But, in the end, AI is not really creative or intelligent as we think of the human experience; it is simply a regenerative approach to data. AI can’t tell a joke and it doesn’t recognize irony. Bottom line, there will never be an AI app to replicate the sound of Jackie MacLean.

AF: Many talented young musicians have spent time in conservatories or colleges. Do you think this has had an effect on the kind of music that we broadly call jazz? As a part of that answer — or separately, if you like — there’s a statistical decrease in the size of the audience for jazz. Do you consider that part of a larger cycle, or will the part jazz plays in America’s cultural dialogue continue to diminish?

Sidran: This of course is the elephant in the room these days. What happens when schools take over jazz? Musicians aspire to teaching, where the work is, rather than to gigging, where the life is. In the process, the music becomes subject to syllabuses and classrooms, which is dramatically different from the culture that originally spawned this music. Some people think that this is the reason we have many good players but very few distinctive stylists these days.

Personally, I believe that swinging and the blues are integral to the development of jazz music and jazz audiences — historically, this music was created to make people feel good, feel less alone, feel part of something bigger than just their day job. Or, as Art Blakey said, “People don’t come to the club to get educated; they come to wash away the dust of everyday life.” Today students consider swing as an option and the blues as a matter of form. It stands to reason that as long as young musicians want to appeal to the listener’s head instead of their heart, jazz will continue to be in decline. Of course it doesn’t help that the New York Times has fired all their jazz writers.

Steve Provizer writes on a range of subjects, most often the arts. He is a musician and blogs about jazz here.

Enlightened and well earned spotlight on Ben Sidrin.

Much truth in this. About music, jazz & the world at large. Thank you.

A Ben Sidran fan since 1985 and this disc brings his conscious and conscientious form back to the fore.

Ben, you’ve never been away, and thanks for that. We’ll do a feature on Ben 28 AUG on KBOO-FM, Portland, OR.