Film Reviews: Tribeca Film Festival 2024, Part One

By David D’Arcy

The 2024 Tribeca Film Festival was predictably celebrity-heavy and substance-light. Yet between the cracks, there were things well worth seeing.

A scene from Xinyan Yu and Max Duncan’s documentary Made in Ethiopia. Photo: Tribeca Film Festival

As always, the best entries at the Tribeca Film Festival tended to be among the documentaries.

Made in Ethiopia by Xinyan Yu and Max Duncan looks at grand plans to modernize that volatile African country. Chinese managers walk around a vast new Eastern Industry Zone outside Addis Ababa and announce, “it’s just like China used to be – just wait.”

Their strategy, more than a decade and a few wars in the making, is to industrialize the country, paying armies of bottom rung workers (mostly women) a pittance per month to assemble clothing. It looks as if the gambit might even work — foreign investors discuss moving operations there — but a few things get in the way in this comic, but eventually discouraging, reality check on the future of globalized production.

There are communication problems, linguistically and culturally. Ethiopians are not attentive to detail, grumble their chagrined Chinese bosses. And a promised expansion could be blocked: local farmers have not been given land they were promised to replace ground that was appropriated for the construction project. Another thing — property adjacent to the farmers’ land turns out to be a development project snuck in by the mayor of the local town.

Motto, the factory’s general manager, is a Chinese woman with a confected company name that local workers can actually pronounce, but she is the one who does the talking. She has devoted a decade to making the project work. Motto has an answer for everything. She even speaks Amharic, and sings in Chinese at a huge party. But her project’s bumpy road gets bumpier. COVID breaks out, slowing plans down, forcing some of the workers to move into their factories. A bloody war shifts the government’s attention and resources to another region.

Made in Ethiopia scrutinizes the economic and cultural assumptions demanded by this growth-at-all costs approach. “Development is the hard truth,” one of the Chinese managers says. “Those who fall behind get trampled on. That’s the crude reality.”

Ethiopia is to be made ready to run the mechanics of modern production. Yet the doc, filled with camera-ready characters and revelatory glimpses of the everyday realities of overnight industrialization, turns out to be a catalogue of growing pains that no one seems to have thought were inevitable. The film also surveys some striking contrasts, starting with the Chinese and Ethiopian physiognomies, moving through conflicts between rich and poor, traditional and modern, industrial and crude (with cow dung mixed by hand with straw and burned instead of wood).

There’s a heart to this film, thanks in part to co-director Duncan’s cinematography. We see that even the Chinese bosses must deal with long-distance burnout: they have families and children whom they miss terribly. The young Ethiopian women who assemble piles of clothing know that they are being underpaid by Chinese managers who envy them for their beauty. Farmers, trapped in a world of pre-technological practices, desperately want their children to be educated out of poverty.

A scene from Simon Klose’s documentary Hacking Hate. Photo: Tribeca Film Festival

This year the top prize for a documentary at Tribeca went to Hacking Hate by Swedish filmmaker Simon Klose. He and reporter My Vingren followed the activities of racists who stoke hate for foreigners online — there are plenty of them in Sweden. Along the way, white supremacists’ connections to Russia and to the corporate titans of social media emerge.

Reviewers of the film have been repeating the mantra that Vingren is a real-life avatar of Lisbeth Salander from The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo — let’s hope that cliché sells this probing film in the US. Bear in mind that the brave, understated Vingren is the real thing. So are the meandering but disturbing trails of AI evidence that she unravels.

Vingren won an award for her reporting on Swedish radio, which involved the journalist creating a false profile and tracking thugs online, with some sites offering Americans recruiting trips for the Wagner Group, another showing avowed fascists in gay dance-like performances. Eventually the threats to Vingren flooded in — enough to make this dedicated reporter wonder if the effort was worth it.

Swedish crime novelists like Stieg Larsson tend to produce sequels. Klose and Vingren have made a doc that makes us eager for more from their research.

A scene from Sandi Simcha DuBowski’s documentary Sabbath Queen. Photo: Tribeca Film Festival

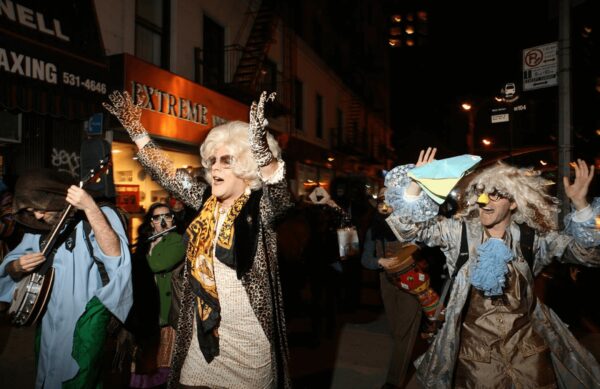

Staying the course while breaking the rules worked for the young Swedish journalist. It could also be a way of describing the vocation of Rabbi Amichai Lau-Lavie, the 39th in a succession of orthodox rabbis and the nephew of the chief rabbi of Israel. Sandi Simcha DuBowski followed Amichai for more than decade — much more — in order to complete the doc Sabbath Queen. It should be noted that Amichai, when in drag wearing a silver sheitel (Yiddish for wig), goes by the name of Rebbetzin Hadassah Gross and opines on all things with a Hungarian accent thicker than goulash.

Amichai arrived in New York’s Warhol days and East Village punk scene after some time off the grid in Israel, and eventually found his way into the God-optional congregation Lab/Shul, which seemed open to anything, including the Rebbetzin, women worshipers (who were banned from the Wailing Wall), and Buddhists (BuJews, as they call themselves). Amichai also undertook rabbinical training; he is ordained a conservative rabbi at the Jewish Theological Seminary in Manhattan. After his ordination, Amichai’s unconventional ministry results in his separation from that institution.

An archival and situational collage, the visual aesthetic of Sabbath Queen depends on where and when Dubowski is filming Amichai, so the textures of his film understandably vary, sometimes abruptly. Its tone ranges from heartfelt and pious to irreverent (sometimes bitchy) wisecracking. Amichai knows that it’s often better to give than to receive.

DuBowski is a longtime observer of those who are underserved or just shunned (a euphemism) by religious institutions. He focused on gay and lesbian Orthodox Jews in the consequential doc Trembling Before G-d (2001) and then extended that scrutiny to gay, lesbian, and transgender Muslims in A Jihad for Love (2007).

Sabbath Queen is a chronicle of one man’s journey struggling with the challenges posed by belonging and separation. Amichai comes off as a man (and woman) who can engage anyone in a conversation about anything. Until he’s confronted by angry Jewish protesters in New York as he holds up a sign calling for peace in Gaza. Well, almost anything.

David D’Arcy lives in New York. For years, he was a programmer for the Haifa International Film Festival in Israel. He writes about art for many publications, including the Art Newspaper. He produced and co-wrote the documentary Portrait of Wally (2012), about the fight over a Nazi-looted painting found at the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan.

Tagged: "Hacking Hate", "Made in Ethiopia", "Sabbath Queen", Max Duncan, My Vingren, Sandi Simcha DuBowski, Simon Klose